Filter Content

- Teeth on Wheels

- Pixevety

- Explaining Australia's school funding debate: what's at stake

- Gonski’s new plan to reinvent Australian schools for the future has this one big flaw

- MSP

- Switch Recruitment

- If you can only do one thing for your children, it should be shared reading.

- Nolan Carpets

- SPOTLIGHT - WESTERN AUSTRALIA

- Programmed Property Maintenance

- Therapy dogs can help reduce student stress, anxiety and improve school attendance

- Camp Australia

- Lessons in compassion from Thai cave rescue.

- PETAA

- ACPPA - Archives - Looking Back to 1993

- WOODS Furniture

- Leading in diverse times - Fr Frank Brennan SJ

- Kidpreneur

- Teaching public issues in Catholic schools

- Utilising Giving to Empower Young Philanthropists

- Teachers Health

- ACPPA Alumni

- WorldStrides

- Just a thought!

ACPPA are proud to be partners with Teeth on Wheels who provide the highest quality dental treatment while making it fun, positive and memorable.

Visit their website and call them to find out more.

Romney Nelson - Teeth on Wheels

Phone: 0414 761 015

Email: romney.n@teethonwheels.com.au

Explaining Australia's school funding debate: what's at stake

10 min read

Estimating how much parents can afford to pay towards their children’s schooling is both vital and politically sensitive. Non-government schools with well-off parents get much less funding from government.

One element of how government estimates this, the school’s SES or socio-economic score, was recently reviewed by the National School Resourcing Board (NSRB), established by the Australian government as part of last year’s Gonski 2.0 funding legislation.

Read more: Gonski 2.0: Is this the school funding plan we have been looking for? Finally, yes

In a nutshell, the NSRB recommended that a direct measure based on pre-tax income is a fairer way to estimate how much non-government school families can contribute to school fees than the current approach, which is based on where families live. The board also showed how smart use of existing data can do this without compromising privacy or forcing schools to collect parents’ tax file numbers.

Here’s why its analysis should prevail, despite strident opposition from some Catholic education leaders, and the claim from the independent schools’ peak body that the current methodology is appropriate.

How funding works today

Under both Labor and Coalition versions of Gonski, the funding target for each school is made up of two components:

-

Base funding: an amount for each student, discounted for non-government schools according to how much parents can afford to pay, known as their “capacity to contribute”

-

Needs-based loadings: an additional amount for each student with higher needs, regardless of their parents’ capacity to contribute.

For most non-government schools, their government funding primarily depends on how much their per-student base funding is discounted.

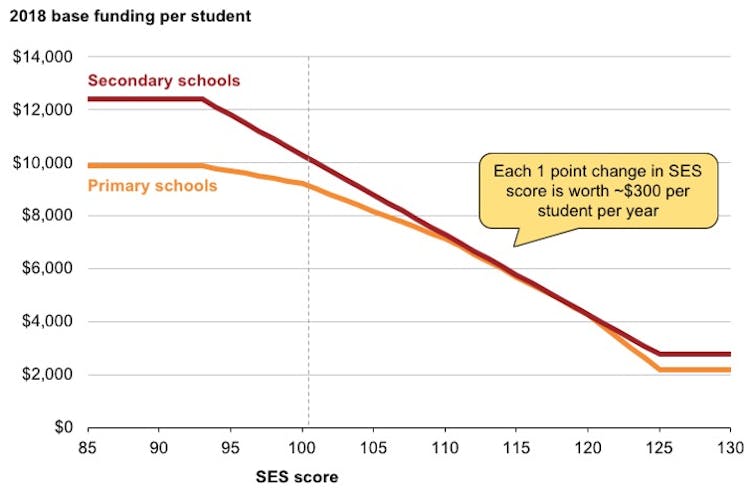

The discount is determined by the school’s SES score. Schools with well-off parents have higher SES scores and received lower base funding per student; schools with less-well-off parents have lower SES scores, and receive more. The average SES score is 100, and 97% of scores fall between 85 and 125.

SES scores are calculated every five years using census data about the average income, education and occupation level in the area where each family lives. This was the best approach available when it was introduced. But families in a given area are not all the same. It would be better to measure family income or wealth directly.

This chart shows why the accuracy of the SES score is so important – small changes matter. Reducing a moderately advantaged school’s SES score by just a single point would increase its government funding by about A$300 for every student every year.

If the SES score of every Catholic school dropped by one point, total Catholic funding would be boosted by about A$90 million in 2018, a 1% increase on current government funding. Lifting the SES score of every independent school by one point would reduce their aggregate government funding by about A$100 million, or roughly 2%.

History matters

A quirk of history helps explain why the SES score methodology is so contentious.

Many non-government schools in Australia - mainly Catholic schools, but also Anglican, Lutheran or some other religious denomination - are part of school systems. These systems receive their government funding in a lump sum, then redistribute it according to their own view of need.

Up until 2017, school systems could choose to be funded according to the average SES score of all their schools, called the system-weighted average. Because the base funding discount formula shown in the chart above is not linear, systems using this approach typically received more government funding.

The biggest beneficiaries of this approach were high-SES Catholic primary schools.

Read more: Catholic schools aren't all the same, and Gonski 2.0 reflects this

Because they were funded as average rather than high-SES schools, they were able to charge dramatically lower fees than independent schools with similarly advantaged parents. This fitted with the Catholic philosophy of keeping primary school fees low, regardless of ability to pay.

Why the SES score needed to be reviewed

In 2017, Education Minister Simon Birmingham removed the system-weighted average as part of his Gonski 2.0 funding reform. This change alone reduced projected Australian government funding to Catholic schools by several billion dollars over a decade, out of a projected A$90 billion or so.

Catholic school leaders were not happy, arguing that the SES score formula is not just inaccurate but systematically biased against Catholic schools. Catholic advocacy was so strident in Victoria’s recent Batman by-election that it grabbed the attention of the Australian Charities and Not-for-Profits Commission.

High SES Catholic schools lost the most – precisely because they benefited most from the distortions of the previous model. That’s why media scare stories about fee increases focused on parish primary schools in leafy green suburbs, not battlers in outer-suburban Catholic schools. Indeed, many low-SES Catholic schools are better off under Gonski 2.0.

But analysis of “winners” and “losers” is not the point. Removing the system-weighted average meant it was necessary to review the SES score formula, which had known flaws.

The job of reviewing the SES score was given to the newly-formed NSRB, which asked for public submissions. I made two main recommendations in my submission:

-

First, the review needed to clarify the policy goal of the capacity-to-contribute element of the funding formula and make it explicit.

-

Second, the review needed to confirm - or refute - whether the SES score is biased against Catholic schools, and to propose a way to remove bias if it exists.

Clarifying the goal of capacity to contribute

The NSRB report clarified the goal of capacity to contribute via three active choices.

It defined capacity to contribute as “a function of the school community’s income and wealth”. So it rejected proposals by Catholic school leaders and others that an updated SES score should take school fees into account. Capacity to contribute is not the same as willingness to pay.

It defined the school community as “the parents and guardians of the students at a school”, so ruled out trying to capture contributions from extended families.

Finally, the NSRB articulated an over-arching principle about funding for non-government schools (p7):

…non-government school communities with the same capacity to contribute should attract the same level of government support.

This clearly rejects the idea that government funding should be higher simply because a school charges low fees. It is also incompatible with the system-weighted average approach.

Not as accurate as a direct measure, but only moderately biased against Catholic schools

The harder job for the NSRB was to delve into the statistical properties of the SES score and what might replace it.

Even with the most fine-grained census data, using small statistical areas of about 400 people, the area-based approach is less accurate than directly measuring each families’ capacity to contribute.

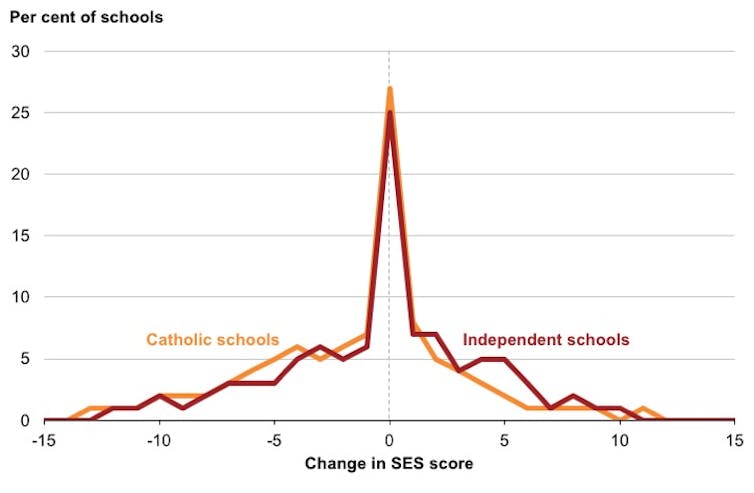

The board analysed how much schools’ SES scores would change if their parents’ income was measured directly. It found little difference for many schools (in some cases part because the school already receives the minimum or maximum funding discount), a big difference for a few, but only moderate bias against Catholic schools.

While most schools would see their effective SES score change by less than three points, nearly one in four schools would change by six or more points, which translates to nearly A$2,000 per student per year.

The area-based approach turns out to be less biased than many thought:

- independent schools are equally likely to see their effective score go up or down; while

- for every eight Catholic schools with scores that go down, five schools have scores that go up.

On average, Catholic school SES scores drop by 1.3 points under a direct model, while independent school SES scores drop by 0.4 points. The size of the bias appears to be about one point.

What is the likely funding impact of moving to a direct measure of income?

The most accurate way to calculate the likely impact on funding for the independent and Catholic school sectors is to model the specific change in SES score for each school. At this stage, only the NSRB’s analysts have the data to do that, and the NSRB did not include that analysis in their report.

However, it is possible to make some educated guesses. I used the chart above to simulate what happens if most schools see little or no change in SES scores while a few schools see bigger changes. I made further refinements to acknowledge that the bias in the current system seems to be largest for high-SES schools, and it may be even larger for big, rich independent schools.

Across a range of scenarios, using a direct measure increases Catholic schools funding by somewhere from A$50 million to A$150 million a year. Independent schools funding is harder to predict, ranging from a decrease of A$100 million or more to even a slight increase in funding. But the independent schools that need the money most will do better under this model than the previous one.

These are big dollars, but still only about 1 or 2% of Australian government funding for each sector.

To put it in context for Catholic schools, the flaws in the current SES score are much smaller than their historic benefit from using a system-weighted average, which would be worth more than A$300 million if re-instated in 2018.

What next?

The NSRB itself has indicated that further work is needed before moving to a direct measure of capacity to contribute. But it has pointed the way with sensible analysis that addresses a range of concerns.

The decision to focus on income is pragmatic. While capacity to contribute is a function of both wealth and income, wealth is harder to measure, for now at least.

The volatility of income data is addressed by using a three-year rolling average. Using the median income further reduces uncertainty for schools, since the median is less affected than the mean if a parent loses their income, or a rich new family joins the school.

Privacy is dealt with by using a new government data-matching approach. Rather than schools having to ask parents for tax file numbers, existing parental address data is passed to the Australian Tax Office, which already has all our income data.

Tax minimisation is dealt with by use of total income rather than taxable income. Independent school leaders are citing supposed counter-examples, like farmers, where total income exaggerates a family’s capacity to contribute. But the use of median income (rather than mean income) minimises this impact.

Including family size strengthens the model further, since a family with multiple children has a lower ability to pay each child’s school fees than a single-child family.

Catholic complaints don’t pass the pub test

Given that Catholic demands to review the SES score have been met, and the answer will mean a little more money for Catholic schools, will the Catholic education leadership be satisfied? While the National Catholic Education Commission has cautiously welcomed the report, other Catholic leaders are less sanguine.

The key battleground is the Catholic desire for high-fee schools to receive less government funding, by including fee income in the way SES scores are calculated.

If the board is right that the key principle is how much parents can afford, then fees charged are irrelevant.

A dissenting view, written by the Catholic representative on the NSRB, is that excluding school fees “doesn’t pass the pub test”. This view focused on schools that charge particularly high fees, most of which are independent schools. But in fact these schools will have high SES scores anyway under a direct measure of parental income, and will receive minimum Commonwealth funding.

The hard question - not addressed in the dissenting view - is why high-SES Catholic schools should get more funding just because they charge lower fees, even when parents could afford to pay more. For example, as the NSRB report shows, there are 10 or so Catholic primary schools where median household incomes are at least A$300,000, but fees are less than A$5,000.

If Catholic leaders want to dispute the NRSB’s principle that “non-government school communities with the same capacity to contribute should attract the same level of government support” they should make that case explicitly.

Views at the pub might differ on that one.

Peter Goss, School Education Program Director, Grattan Institute

This article was originally published on The Conversation. Read the original article.

Read LessGonski’s new plan to reinvent Australian schools for the future has this one big flaw

My favourite episode of the American television comedy Seinfeld is the one titled “The Opposite”. Jerry Seinfeld’s mate, George, was always down on his luck until one day he decided to do the opposite of everything that came into his head.

His natural instincts had gotten him nowhere. He had no job and was still living with his parents well into adulthood. The results of George’s decision to do the opposite were that he changed his whole daily routine, found a new partner who liked his faults and landed an amazing job with the New York Yankees.

I was reminded of George in “The Opposite” episode when the Australian government launched its new Gonski report, Review to Achieve Educational Excellence in Australian Schools.

The review challenges the current schooling system by calling out the vestiges of the assembly line industrial age of education and the current lack of investment in “individualized” learning and future-focused skills. It calls for new types of online formative assessment (that is assessment carried out by teachers in their classrooms as part of the teaching process) and a different progression of learning schemes to focus on early literacy and numeracy skills. It wants us to reinvent years 11 and 12 of high school, to make them more creativity and innovation-based.

This is sounding like “The Opposite” to me.

The premise of this new scheme is line with the best thinkers on education in the world, from Thomas R. Guskey who encourages teachers to “make well designed assessments an integral part of the instructional process”, to Yong Zhao who wants the public to be informed of the “side effects of sweeping education policies” such school choice. It is also following the type of reforms made in the most educationally progressive nations in the world (yes, sorry folks, Finland, Switzerland, Belgium and the Netherlands).

However, disappointingly, the assessment recommendations are a reboot of more of the same, or worse.

The review is advocating for assembly-line type assessments in the early years. That is the opposite of how educators boost literacy and numeracy skills in young children. And here again I think of Zhao and his side effects warnings, as he puts it : “This practice can help your children become a better student, but it may make her less creative”; or “This program helps improve your students’ reading scores, but it may make them hate reading forever.”

The glaring contradiction in the report, as I see it, its that it asks for massive changes to an assembly-line reality by advocating for more assessment assembly-lines. Ken Boston in his recent commentary speaks to this by advocating that this is a “evolution not a revolution.” What is missing from this argument for learning progressions is the assumption that learning can be standardized across children. Chunking a NAPLAN component a day or week turns teachers into test givers and paper pushers rather than gifted learning scientists negotiating each child’s journey through the curriculum so that they are engaged and inspired, not lab rats.

I also noticed that some of the recommendations on learning progressions in the report have already failed elsewhere and have been dumped for that reason. For example New Zealand’s system, where young people faced ‘a test a day’, resulted in standards that continued to fall anyway in international comparisons. So they scrapped their national assessment program altogether.

What can we do?

I recommend that all of us who work in schools and with student performance data spend time this year advocating for reinventing the opposite of our current systems; not for more government-run assessment but for less.

We want to prepare children to be successful in their futures and to do that they need knowledge, skills and dispositions to be passionate, vibrant, dynamic, curious, open-minded, engaged (and literate and numerate) participants in their own journeys. We can’t assembly-line assess that.

If we are truly interested in improving literacy we need to read more with children. And while I know that this is told to parents and teachers over and over, the reality is we don’t do enough of it. It also means getting more books in the hands (yes, old school books) of infants, toddlers and young children. Again, we know this, but I believe we don’t to enough to make sure it happens. There should be at least 50 books in each home (age appropriate) by the time a child is five years old. The secret to literacy is reading more not assessing more.

Most importantly, we need high quality early childhood education for all children, not just the wealthy. Some of the recent practices downgrade early childhood workers to carer/babysitter status in salary and qualifications, just at the time we know so much more about this vital time of building cognitive capacity and hopefulness in the developing brain.

And basic, but usually ignored in education reform debates, is the glaring need for better supplementary health care for working class families in Australia. One that allows affordable dental, eye and specialist care so that these crucial wellbeing issues are not factors that negatively impact a child’s development.

In Australia we have doubled down on entrance and exit requirements for initial teacher education, now we have proposed new standardized formative assessment schemes, and these all piggy back on our mostly failed summative assessment systems (where children are tested at the end of their studies. The proposed progressions of learning assessments narrowly simplify the process of learning into linear chunks that are not how young people learn. And they will create false measures of learning. Teachers should not have their pedagogical imaginations stripped to conform to practices that are not congruent with promoting learning.

One urban legend definition of insanity is “doing the same things over and over again and expecting better results”. When assembly line schooling is transformed to individualized learning, but the assessment scheme is from the same original mindset, we have the cart in front of the horse. And that is insane. “Stop, drop and test” assessment schemes are obsolete. It is time we in the field called this out and moved forward to build learning centers instead of testing centers. Let’s pull an “opposite George” out of our hats!

Dr John Fischetti is Professor and Head of School/Dean of Education at the University of Newcastle. John’s research focuses on reframing teacher education, school reform and learner-focussed teaching. John can be reached at john.fischetti@newcastle.edu.au or on twitter @fischettij

This article was originally published in EduResearch Matters, the Australian Association for Research In Education blog.

Read LessIf you can only do one thing for your children, it should be shared reading.

Ameneh Shahaeian, Australian Catholic University and Cen Wang, Charles Sturt University

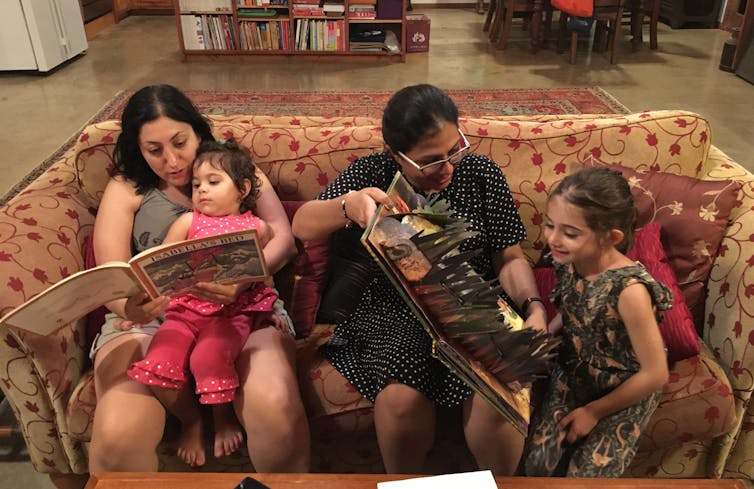

Reading to children is beneficial in many ways. Books offer a unique opportunity for children to become familiar with new vocabularies; the type of words not often used in day-to-day conversation. Books also provide a context for developing knowledge of abstract ideas for children. When an adult reads a book to a child, they often label pictures, talk about activities in the book, solve problems together and teach them new words and concepts.

Reading to very young children can have long-lasting benefits for their later school success, not only in literacy but also in mathematics. Adding to this, early shared reading particularly helps children from disadvantaged families defy limitations associated with their socio-economic status. So, if there is only one thing you have time to do with your children, it should be reading to and with them.

Read your way to the top

Parents have long been encouraged to read more to their children. There have been many initiatives, challenges, and programs aiming to increase individual reading time and shared reading time between parents and children. These include the Australian Reading Hour Campaign, the Premier’s Reading Challenge, Let’s Read, and others.

Read more: Five tips to help you make the most of reading to your children

What’s still not clear is which specific skills improve while parents read to their children, and whether the benefit of shared reading is due to other things parents do that help their children thrive at school and beyond.

That is: is it really book reading that’s beneficial or is it because parents who read more to their children also provide a lot of other resources, and engage in a range of other activities with their children?

This was what we looked at in our study. We used data from a large scale nationwide study called the Longitudinal Study of Australian Children (LSAC). It has followed the development of 10,000 children and their families since 2004.

The sample we studied consists of 4,768 children from the cohort that was zero to one year old when the study commenced. During face-to-face interviews with trained LSAC interviewers, parents reported the frequency of them reading to their children at the age of two every week.

The LSAC then followed these children until they were four and eight years old. The good news is the majority of parents reported reading to their children at least three days a week. Specifically, 61.6% of the parents reported reading to their children every day and 21.1% of the parents read to their children between three to five days a week.

Read more: Enjoyment of reading, not mechanics of reading, can improve literacy for boys

Our study showed the benefits of shared reading with children during early childhood at two to three years old is long-lasting. The more frequently parents read to their children when they were two years old, the more likely their children had better knowledge of spoken words and early academic skills such as recognising and copying geometric shapes, and writing letters, words and numbers, two years later when children were four to five years old.

What’s more, frequent early shared reading was linked to better performance in NAPLAN reading, writing, spelling and grammar. More surprisingly it was also linked to mathematics even six years later when children were eight to nine years old in year three.

The most encouraging finding is that children from disadvantaged families benefited more from shared book reading. This suggests increasing the frequency of book reading is a viable way for disadvantaged families to support their children’s vocabulary knowledge and general academic achievement.

To address whether the benefits of shared reading are a product of other factors associated with parents and families, we controlled for the effect of a range of potential confounding factors. These include indicators of children’s intelligence, the number of children’s books at home, and home activities that parents engage with children other than reading. These would include drawing pictures or doing art activities with children, playing music together, playing with toys or games, and exercising together.

Even though we controlled for these other factors, the long-term importance of early shared reading still holds.

Suggestions for parents

Read more to your children and with your children. Whenever you get a chance, even if it’s only ten minutes, engage in shared reading activities.

Read more: Research shows the importance of parents reading with children – even after children can read

We also suggest parents make a reading session interactive. For example, parents are encouraged to ask children questions, such as if they know the vocabulary and ask them to guess the story and what the story characters will do. Try to make the reading a learning session.

![]() Finally, not all books are created equal. Parents are encouraged to choose the most suitable books for their child’s age to reap the most benefits of early shared reading.

Finally, not all books are created equal. Parents are encouraged to choose the most suitable books for their child’s age to reap the most benefits of early shared reading.

Ameneh Shahaeian, Research Fellow in Developmental and Educational Psychology, Australian Catholic University and Cen Wang, Research Fellow in Educational and Developmental Psychology, Charles Sturt University

This article was originally published on The Conversation. Read the original article.

Read Less

The wonderful thing about being a Principal in the Kimberley is that you get to be a jack of all trades. At first, I believed I was employed for this position because of my contextual knowledge, my hardworking disposition and my willingness to live a life of Witness. All of this is true, and so much more. I realised very quickly that I was also selected because of my ability to wear many hats. Some days I wear the hat of plumber, electrician, housing manager, other days the hat of a social worker, nurse, counsellor and every day I seem to where the hat of the IT consultant. These different roles have me climbing under buildings to locate a leak, searching the school to identify an electrical fault and squeezing in behind the server rack to restart the server in the hope that the old turn it off and on again trick will work its magic. These aspects of the role are the ones I find easiest to deal with, faults in a machine or piece of equipment don’t challenge you as does our care for each child and their family within our community.

It is this side of the role that I find can really tax the emotions. As you work with families to assess and support their child’s mental health, ensure their child’s safety within the community or work with the Department of Communities to advocate for the welfare of our students, you give so much of yourself and separating your emotions from the job is easier said than done. All this takes time, effort, heart and definitely an attitude of partnership. This work can only be done in partnership with our local school community.

So why get up and do it again and again and again, because amongst all that, there is joy. And finding the joy in all the little things is the only way not just to survive being a Principal in the Kimberley but to succeed. There is joy in seeing a student’s attendance improve because of the work that has been done with their family. There is joy in hearing a student share their reading level proudly with all their friends and teachers. There is joy in seeing a student use the problem solving strategies they have been taught to deal with an issue with one of their peers. There is joy in seeing parents become more involved in their child’s education. There is joy in watching the new graduates who come to our school grow into strong and confident teachers. There is joy in the relationships formed between our staff, with our children and families within the community. There is joy in the beautiful country we get to live, work and play in each day.

The role is incredibly diverse and requires resourcefulness and the ability to adapt. The most important lesson learnt is to take time to find the many moments of joy that lift the heart and spirit.

Gabrielle Franco - St Joseph's School Wyndham

Email: Gabrielle.Franco@cewa.edu.au

Therapy dogs can help reduce student stress, anxiety and improve school attendance

5 min read

Christine Grove, Monash University and Linda Henderson, Monash University

In the wake of the schools shootings in Florida, therapy dogs have been used as a way to provide comfort and support for students returning to school. Research has shown therapy dogs can reduce stress and provide a sense of connection in difficult situations.

Given the impact therapy dogs can have on student well-being, schools and universities are increasingly adopting therapy dog programs as an inexpensive way of providing social and emotional support for students.

What are therapy dogs?

It’s important to note therapy dogs are not service dogs. A service dog is an assistance dog that focuses on its owner to the exclusion of all else. Service dogs are trained to provide specific support for individuals with disabilities such as visual or hearing difficulties, seizure disorders, mobility challenges, and/or diabetes.

The role of therapy dogs is to react and respond to people and their environment, under the guidance and direction of their owner. For example, an individual might be encouraged to gently pat or talk to a dog to teach sensitive touch and help them be calm.

Therapy dogs can also be used as part of animal assisted therapy. This aims to improve a person’s social, cognitive and emotional functioning. A health care professional who uses a therapy dog in treatment may be viewed as less threatening, potentially increasing the connection between the client and professional.

There are also animal-assisted activities, which is an umbrella term covering many different ways animals can be used to help humans. One example is to facilitate emotional or physical mental health and wellbeing through pet therapy or the presence of therapy dogs. These activities aren’t necessarily overseen by a professional, nor are they specific psychological interventions.

Research suggests using therapy dogs in response to traumatic events can help reduce symptoms of depression, post traumatic stress disorder and anxiety.

So, what can happen psychologically for people using therapy dogs?

The human-animal bond

The human-animal bond can impact people and animals in positive ways. Research shows therapy dogs can reduce stress physiologically (cortisol levels) and increase attachment responses that trigger oxytocin – a hormone that increases trust in humans.

Dogs also react positively to animal-assisted activities. In response to the human-animal bond, dogs produce oxytocin and decrease their cortisol levels when connecting with their owner. Often dogs feel the same when engaging in animal assisted activities as if they were at home, depending on the environmental context.

Benefits of therapy dogs

Animal assisted therapy can:

-

teach empathy and appropriate interpersonal skills

-

help individuals develop social skills

-

be soothing and the presence of animals can more quickly build rapport between the professional and client, and

-

improve individual’s skills to pick up social cues imperative to human relationships. Professionals can process that information and use it to help clients see how their behaviour affects others.

More recently, therapy dogs are being used as a form of engagement with students at school and university.

Benefits of therapy dogs at school

A recent report highlighted children working with therapy dogs experienced increased motivation for learning, resulting in improved outcomes.

Therapy dogs are being used to support children with social and emotional learning needs, which in turn can assist with literacy development.

Research into the effects of therapy dogs in schools is showing a range of benefits including:

-

decreases in learner anxiety behaviours resulting in improved learning outcomes, such as increases in reading and writing levels

-

positive changes towards learning and improved motivation, and

-

enhanced relationships with peers and teachers due to experiencing trust and unconditional love from a therapy dog. This in turn helps students learn how to express their feelings and enter into more trusting relationships.

Despite these known benefits, many schools choose not to have therapy dog programs due to perceived risks. These range from concerns about sanitation issues to the suitability of dog temperament when working with children. But therapy dogs and owners are carefully selected and put through a strict testing regime prior to acceptance into any program.

The main reason for the lack of take up has been linked to the limited research into the benefits of therapy dogs in schools.

Benefits of therapy dogs at university

Researchers have found university students reported significantly less stress and anxiety, and increased happiness and energy, immediately following spending time in a drop-in session with a dog present, when compared to a control group of students who didn’t spend any time with a therapy dog.

Generally, therapy dog programs rely on volunteer organisations. One example is Story Dogs, who currently have 323 volunteer dog teams in 185 schools across NSW, Queensland, Victoria, Tasmania, SA, WA, and ACT. In total, they help 1,615 children each week.

![]() Research into these programs is needed to help further understand the impacts of therapy dogs, especially on student learning and academic outcomes. Lack of funding is setting this research back. University partnerships are one solution to address this.

Research into these programs is needed to help further understand the impacts of therapy dogs, especially on student learning and academic outcomes. Lack of funding is setting this research back. University partnerships are one solution to address this.

Christine Grove, Educational Psychologist and Lecturer, Monash University and Linda Henderson, Senior Lecturer, Monash University

This article was originally published on The Conversation. Read the original article.

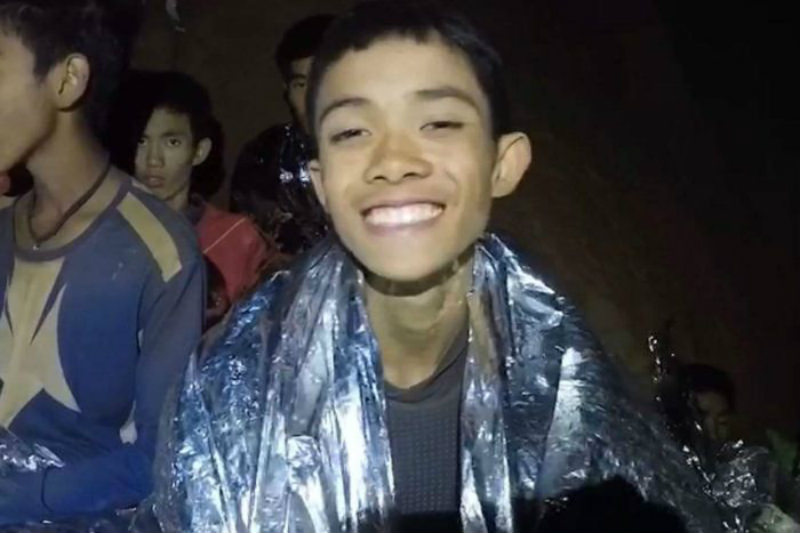

Read LessLessons in compassion from Thai cave rescue.

It was hard not to be moved, encouraged and impressed by the plight and rescue of the boys marooned in the North Thailand cave. People around the world responded to the boys' youth and the danger they faced and by the generosity and skill displayed in their rescue.

I was particularly moved because what I was seeing done for village boys in Thailand was so different from what was appearing in our adult media: bank executives and insurers profiting by imposing misery on their clients; evidence of unethical and extortionate behaviour in so many businesses that it seemed a royal commission into almost any section of corporate behaviour would yield similar results.

I was particularly moved because what I was seeing done for village boys in Thailand was so different from what was appearing in our adult media: bank executives and insurers profiting by imposing misery on their clients; evidence of unethical and extortionate behaviour in so many businesses that it seemed a royal commission into almost any section of corporate behaviour would yield similar results.

In addition to that, the rat run from international agreements and diplomatic conventions and from anything not grounded in crude self-interest, and the snarling, demeaning exchanges characteristic of public life.

All these made it seem that the neoliberal vision of human well being as unregulated competition for wealth, encapsulated in browbreating poor and grieving Indigenous women into taking out unwanted funeral insurance, had captured the minds and hearts of the whole world.

Watched from a distance, the events in Northern Thailand showed that this was not so. They disclosed a mature human response to misfortune and a sophisticated culture. The news that the boys were lost in the cave generated concern and attention throughout Thailand.

These boys were everyone's sons. Volunteers flowed in from all parts of Thailand, offering their labour and their gifts to the people who could rescue them. International volunteers also offered their services, and were welcomed for the skills they brought and incorporated into an international team that worked cooperatively and tirelessly at the risk of their lives. This encapsulated a society working effectively out of compassion.

The Thai coordinators of the rescue also emphasised communal relationships over individual interests. They kept the media informed of the situation and what was being done each day, but kept them away from the cave, the divers and the children. They did not inform the parents that their own child had been rescued until the safety of all was guaranteed, so holding them together in mutual support.

These things could be seen clearly. But a deeper Thai cultural strand ran in the story, the counterpart of the emphasis on the competitive individual in the West and in business everywhere.

Its strength can be gauged when we ponder how the boys apparently emerged undamaged after spending more than a week together in a dark cave, without light, with very little food, without the support of family, and unsure whether their whereabouts would be known or that they would be found alive. That is the stuff of nightmares and of isolation. Yet they seem to have been brought together rather than isolated by the experience.

Their resilience speaks of a strong Buddhist culture in which the boys were used to struggle, found meaning in attending to the welfare of others rather than their own, and drew strength from meditative practices that set their perilous predicament within a broader human horizon.

This culture of compassion and of community based on respect was also displayed in the handling of the rescue and the subsequent care for the boys. It spoke most deeply to those of us who watched from a distance.

Events like these are epiphanies that give light and hope in times of darkness. Afterwards we may expect that competitive individuals and media will see a buck to be made out of the boys and their experience. They will try to seduce the boys and their families out of their own culture and then spit them out. We may hope that the example and the values of their admirable coach will persuade the Wild Boars and their families not to sacrifice their cultural horns.

Andrew Hamilton is consulting editor of Eureka Street.

Andrew Hamilton is consulting editor of Eureka Street.

Read Less

ACPPA - Archives - Looking Back to 1993

For 8 years ACPPA held extremely successful annual conferences, usually immediately prior to the APPA Conference and at the same venue. The 1993 conference was scheduled for Western Australia. The WA planning team had been meeting for some time and raised some concerns with this arrangement. They identified three areas that needed to be addressed.

- As many of the ACPPA delegates also attended the APPA Conference it meant a full week out of school.

- The cost of presenting a conference with national and international speakers was significant.

- The only way to reduce registration costs was to be able to attract a high level of sponsorship. As both conferences called on the same core group of sponsors this was a big ask.

Both the Government School Principals and the Catholic School Principals were well into initial planning for the 1993 Conference and it became blindingly obvious that to engage the speakers they wished the cost for each conference was quite staggering. After some lateral thinking by members of the two associations it was agreed that serious discussion should take place in regard to making it a combined conference. 1993 would celebrate 150 years of Catholic Education, and the planned title for the ACPPA conference was Catholic Education – A National Treasure, while 1993 was also 100 years of Government School Education in WA, with the APPA Conference to be titled The Magic of Primary Education. With this in mind it was an easy decision to make it a combined conference with the amended title of Primary Education – Something to Celebrate. It was also decided to invite the Independent sector’s Junior School Heads Association to have representative on the planning committee and become involved in the conference.

Now that a more realistic financial base was established it was possible for the planning committee to invite Michael Fullan, Dean of Education at the University of Ontario, to be the lead speaker, along with Professor Hedley Beare, from the University of Melbourne, Dr Patrice Cooke from the Institute of Human Development and Dr John Hattie from University of WA. As the APPA Conference had always included business sessions that were focused on the issues of most concern to the Government School Sector, it was further decided that there would be some sessions where the sectors could meet separately. To this end Sr Jan Gray RSM from the University of Notre Dame and John Goodfellow from Mt Lillydale Mercy College in Victoria would lead sessions specifically of interest to the Catholic School Principals.

A statement from the ACPPA Executive in support of the Combined Conference said, “The decision to join with APPA in hosting the first combined national conference in Perth later this year is a sure indication of the strong relations which exist in Western Australia between principals in government and non-government schools. Such co-operation and unity is something we should all be proud of and thankful for as it is likely to lead to more effective representation of issues which are of importance to all principals.”

How true that prediction was to be!

The 1994 ACPPA Executive who were elected at the 1993 ACPPA AGM in Perth: Jim Green, President; Greg Wyss, Treasurer; John Last, Secretary, all from WA.

Pictured at the 1993 APPA/ACPPA Conference: Frank Hennessy, Retiring President; Michael Fullan, Keynote Speaker; Sir Francis Burt, Governor of WA who officially opened the conference; Keith Davies, Principal WA.

Kevin Clancy

Email: kclancy@ozemail.com.au

Leading in diverse times - Fr Frank Brennan SJ

Long Read -20 mins+

Tropical and Topical, 2018 National Catholic Principals' Conference, Cairns Convention Centre, 16 July 2018. Listen

I thank John Loch for his very Rockhampton introduction. I join with you acknowledging the traditional owners of the land on which we meet and honour their elders, past, present and future. Dan McMahon opened this conference with a bold declaration: 'Our bruised and battered Church has never been in greater need of our schools.'

Building on the challenge that Kristina Keneally put before you last evening with the suggestion that you might 'throw the Hail Mary pass', thereby saving the day for our beleaguered Church, I want to console you this morning with Pope Francis's disturbing reassurance: 'A faith that does not trouble us, is a troubled faith; a faith that does not make us grow, is a faith that needs to grow'.

Building on the challenge that Kristina Keneally put before you last evening with the suggestion that you might 'throw the Hail Mary pass', thereby saving the day for our beleaguered Church, I want to console you this morning with Pope Francis's disturbing reassurance: 'A faith that does not trouble us, is a troubled faith; a faith that does not make us grow, is a faith that needs to grow'.

You school principals are the nurturers of the Catholic imagination, the witnesses to Catholic social teaching, helping to form and inform the consciences of your students and staff, and being the convenors and presiders at the most regular liturgies attended by the majority of young people who identify in any way as Catholic.

This conference provides you with the opportunity conscientiously to fire that imagination, to strengthen that witness, and to confirm you in your role as enablers helping your staff and students to shape their world view, their understanding of sin and grace, of oppression and liberation, of mercy and forgiveness.

A tropical perspective

I've been coming to Cairns on and off for the last 40 years. When I first came here as a Jesuit, I met the then bishop John Torpie. I was wondering what possibilities there might be for a ministry amongst Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander people in this diocese. He told me, 'We don't have any real problem here, because very few of them are Catholic.' Established mindsets and ways of setting apostolic priorities change over time.

Then in the early '80s I used to come more regularly when John Bathersby was the bishop. I used to visit Far North Queensland making my way to the remote Aboriginal communities for ongoing consultations about land rights and community government. I often stayed at the bishop's house in Cairns. Coming down to breakfast one morning, I asked Batts what was on his agenda for the day. He was a little despondent, replying that he had to attend a meeting of the ministers' fraternal. I have always believed in trying to cheer up bishops over breakfast, so I remarked that such ecumenical activity was a good and worthy thing. Bishop John said, 'Yes, but they want me to sign a letter opposing the building of a casino.' I thought that was not such a bad thing either. He scratched his pate and lamented, 'But it's a bit hard when your old man was an SP bookie.' It takes all types in this world and in our church. Even our most senior church elders are shaped by their own backgrounds and family situations.

Our MC John Loch was wondering whether any good could come out of Rockhampton (Queensland's Nazareth). I'm happy to tell you that the answer is a resounding 'Yes'. My father came from Rockhampton. His own father was the judge there for many years. Last week, Dad, aged 90, published a letter to the editor in The Australian. It's only the second time he has done so. The first time was in August 1971 when Sir John Bjelke Petersen declared a state of emergency here in Queensland, so the police could exercise untrammelled power against protesters agitating against the all-white Springbok rugby tour. My father suggested that lawmakers as well as protesters needed to examine their consciences so that the rule of law might be protected. After he published the letter, Queensland's leading barrister of the day told him that he would never become a judge. Well, he ended up as Chief Justice of Australia having written the lead judgment in the Mabo Case. His second letter appeared in The Australian on 12 July 2018:

'The world watched and waited and millions prayed for the safe deliverance of the boys and their rescuers. The prayers were offered in every faith; they strengthened and supported the compassion, the courage and the competence of the rescuers.

'Perhaps the universal concern for those in peril, and the brave and selfless devotion of their rescuers, have shown us how to make our world a better place.'

That letter is the fruit of a lifetime's prayerful reflection on what it is to be a Christian in our complex, multicultural, multi-religious, increasingly secularist world. We don't know the future shape of our world, but we know the contours of hope which point to a better life for all.

You have asked me to be 'tropical and topical' and to reflection on 'Leading in Diverse Times in the Church and in the World'. Let me put a couple of tropical questions. As a school principal flying back south after this conference, how should I be feeling and what things should I be alert to, ensuring that my church is more accountable and transparent and true to the gospel in the wake of the royal commission, what should I be thinking about school funding, what should be my approach to employment of LGBTI staff and to pastoral care of LGBTI students in the wake of the same sex marriage debate, and what should I be drawing from Pope Francis to animate my school community about stewardship of the environment, responsibility for the poor, spiritual contentment in an age of disruption, and getting the mix right of truth, justice, love, mercy and joy? How are we to give women their place at the table when they cannot preside at eucharist? How are we to assure Indigenous Australians their place at the table when governments make laws and policies impacting especially on them and their heritage?

This conference should be a sacramental moment, food for the journey, sustaining us and providing a sense of true north as we head south into the complexity of the family relations of our students and staff and into the disruption of our politics and public life.

I had the good fortune to arrive a couple of days early for the conference. On Saturday, I had the splendid opportunity, courtesy of your conference organisers, to visit the outer reef on the Quicksilver. It was a stunning experience. I called to mind Pope Francis's declaration in Laudato Si':

'If we approach nature and the environment without openness to awe and wonder, if we no longer speak the language of fraternity and beauty in our relationship with the world, our attitude will be that of masters, consumers, ruthless exploiters, unable to set limits on their immediate needs. By contrast, if we feel intimately united with all that exists, then sobriety and care will well up spontaneously.'

Yesterday afternoon, I walked here to the convention centre and took a detour to the Cairns Indigenous Arts Fair. There was art from all the remote indigenous communities in Cape York and in the Torres Strait and wonderful displays of dance and song. I called to mind Pope Francis's visit to the Second World Meeting of the Popular Movements at the Expo Feria Exhibition Centre in Santa Cruz de la Sierra, Bolivia 3 years ago. He told the participants:

'To our brothers and sisters in the Latin American indigenous movement, allow me to express my deep affection and appreciation of their efforts to bring peoples and cultures together in a form of coexistence which I would call polyhedric, where each group preserves its own identity by building together a plurality which does not threaten but rather reinforces unity. Your quest for an interculturalism, which combines the defence of the rights of the native peoples with respect for the territorial integrity of states, is for all.'

You as school principals are called to bring students and staff from diverse cultures and backgrounds together in a form of coexistence where each group preserves its own identity by building a school community which does not threaten but rather reinforces unity. I daresay that even John Torpie would have rejoiced if he were alive today and saw the indigenous art fair. He might even wonder where is the Church in all this vitality, hope and imagination.

As a nation, we are presently bogged down in working out how best to recognise Indigenous Australians in our Constitution. Senator Kristina Keneally, who was a member of Referendum Council forcefully espoused the Uluru Statement from the Heart in her opening keynote address last night. I've been involved in this difficult space for the last three decades. I wish I could see the matter as clearly and simply as Kristina does. But I can't. Just last week, the great Aboriginal leader Noel Pearson had cause to comment on my approach to these matters. I was very privileged to be describe by him as 'my great and old friend Fr. Frank Brennan, the Jesuit lawyer and priest'. But that meant I was on notice that a rocket was coming. Noel said:

'I have known Frank for over 35 years, since I was a very young man and his commitment to the Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander people and the cause of reconciliation has been long-held and profound. However, I think the mistake Frank made in this debate and in other debates in which I have been truculent with him, is in thinking that reconciliation is about compromise. That Indigenous people should compromise their current position in order to achieve reconciliation. That cannot be the case. For people who have lost everything, how could there be an expectation of further compromise? This is about common ground, locating common ground and, for my taste, Frank has mistaken the search for common ground with his predilection for finding compromise. He was mistaken in this and I pray that in the journey that now begins afresh, he will understand that.'

I think it is a very long, difficult and winding road from Uluru to constitutional recognition. I don't know how you find common ground except by compromise, unless of course there is agreement about the principles at stake and agreement that there is only one way to apply those principles to the challenges at hand in the contemporary context. Even amongst indigenous Australians there is no unanimity on that.

230 years after settlement or conquest, and after generations of migration from every other country on earth, common ground will be found and occupied only by those who are prepared to come together in trust seeking compromise – a bit like Mr Fourmile and his white Irish wife and their precocious 7-year-old daughter finding common ground through the everyday compromises of family life.

To find common ground, we must be committed to trusting conversation. We need to build bridges and forge relationships across differences. I think we need to be uncompromising in stating our principles – our understanding of what is right and wrong, our understanding of what is optimal and what is not. But then we need to be able to compromise in effecting laws and policies which give due weight to the varying viewpoints agitated in the process of political deliberation. And if that goes for laws and policies which can be drawn up today and changed tomorrow, it must go even more for constitutional change which requires a supermajority to adopt, which binds even the elected lawmakers (no matter what their popular mandate) and which is very difficult to change once enacted.

You school principals know that the art of leadership is found in the political deliberation able to find the solution to a problem which is appropriately principled, workable and popular.

On approach to the Convention Centre yesterday and again this morning, I met some protesters who are upset that Senator Kristina Keneally and I are keynote speakers. They disapprove of what each of us said during the same sex marriage plebiscite last year. Their protest is being co-ordinated out of Virginia in the USA by a group called 'Church Militant'. Yesterday afternoon, I introduced myself to the handful of protesters and offered to chat anytime. They declined. One said, 'We know what you think.' My offer to chat over the next couple of days here in Cairns remains open. All was peaceful as you would expect and hope in Cairns. Nothing is to be lost by greeting these protesters as we come and go.

Steps for leading in diverse times

Pope Francis gives us four steps for leading in diverse times so that our school communities might be more inclusive and more expansive. His teachings in Laudato Si' and Amoris Laetitia urge us to expand our horizon of concern to include the whole of creation, and to expand our circle of inclusion to welcome all to the table, whether that be the table of learning, the table of public deliberation, or even the table of the Lord.

1. Embedded in the mess and complexity of life and the world

Francis never tires of telling us that Jesus wants a Church attentive to the goodness which the Holy Spirit sows in the midst of human weakness, a Mother who, while clearly expressing her objective teaching, 'always does what good she can, even if in the process, her shoes get soiled by the mud of the street'. Jesus 'expects us to stop looking for those personal or communal niches which shelter us from the maelstrom of human misfortune, and instead to enter into the reality of other people's lives and to know the power of tenderness. Whenever we do so, our lives become wonderfully complicated'. The days of the firm school principal who sat in the office issuing clear directives for inclusion and exclusion have gone. As leaders we are invited to display tenderness and not to be threatened by complexity as we immerse ourselves in the lived reality of our staff and students, and their families which come in all shapes and sizes.

2. Bringing conscience to bear

The cardinals and archbishops who have expressed their public upset with Pope Francis have done us all a favour. There is no getting away from the fact that Francis sees conscience having more work to do than simply determining church teaching and applying it to the case at hand. Each of us is called to form and inform our conscience and to that conscience be true. This is how Pope Francis explains the threefold role of conscience as we make our objective assessments, generous responses, and prayers for mercy:

'Yet conscience can do more than recognize that a given situation does not correspond objectively to the overall demands of the Gospel. It can also recognize with sincerity and honesty what for now is the most generous response which can be given to God and come to see with a certain moral security that it is what God himself is asking amid the concrete complexity of one's limits, while yet not fully the objective ideal. In any event, let us recall that this discernment is dynamic; it must remain ever open to new stages of growth and to new decisions which can enable the ideal to be more fully realized.'

3. Transforming the mess and complexity of life through participation in the sacramental life of the church

Francis says that a person can be living in God's grace while 'in an objective situation of sin', and that the sacraments, including the Eucharist might help, because the Eucharist 'is not a prize for the perfect, but a powerful medicine and nourishment for the weak'. Francis demands that pastors and theologians not only be faithful to the Church but also be 'honest, realistic and creative' when confronting the diverse reality of families in the modern world. Just as he discounts those who have 'an immoderate desire for total change without sufficient reflection or grounding', so too he dismisses those who 'would solve everything by applying general rules or deriving undue conclusions from particular theological considerations'.

4. Always discerning

In his latest Apostolic Exhortation Gaudete et Exsultate, Francis says:

'Certainly, spiritual discernment does not exclude existential, psychological, sociological or moral insights drawn from the human sciences. At the same time, it transcends them. Nor are the Church's sound norms sufficient. We should always remember that discernment is a grace. Even though it includes reason and prudence, it goes beyond them, for it seeks a glimpse of that unique and mysterious plan that God has for each of us, which takes shape amid so many varied situations and limitations. It involves more than my temporal well-being, my satisfaction at having accomplished something useful, or even my desire for peace of mind. It has to do with the meaning of my life before the Father who knows and loves me, with the real purpose of my life, which nobody knows better than he. Ultimately, discernment leads to the wellspring of undying life: to know the Father, the only true God, and the one whom he has sent, Jesus Christ (cf. Jn 17:3). It requires no special abilities, nor is it only for the more intelligent or better educated. The Father readily reveals himself to the lowly (cf. Mt 11:25).'

For you as school principals, the difficult decisions are not choosing between right and wrong, but discerning the greater good in the light of your students' needs, the resources you have to hand, and the challenges of the world into which those students are stepping. The Church's norms, though sound, are not sufficient. It's not just a matter of collating the evidence and making a prudent judgment. There's something bolder we're asked for: the grace born of a deep interior freedom and a passion to do more for the breaking in of the Kingdom of God here and now in my staff room and in my playground.

Topical issues deserving our consideration

1. Women and the Church

Kristina Keneally was unapologetic in putting the place of women in our church front and centre. And so we should. How do we make our church credible in a world where human rights and the principle of non-discrimination are trumps? The Church's teachings on moral issues will maintain currency in the world in future only to the extent that the Church's own structures and actions reflect the rhetoric of human rights, and only to the extent that those rights are enjoyed by all within the Church. The place of women in our Church and the respect shown to laity when church fathers deliberate and pontificate are key indicators of the Church's capacity to be credible when agitating its distinctive perspective on the human rights challenges of the age.

Ours is the Church of the west which is most behind in accommodating the place for women at the Eucharistic table. When asked about women's ordination in June 2013, Pope Francis replied, 'The Church has spoken and says no. . . . That door is closed.' The one consolation is that he used the image of a door and not a wall. At least a door can be opened if you have the key or if you are able to prise it with force over time.

Francis wrote in Evangelii Gaudium, 'The reservation of the priesthood to males, as a sign of Christ the Spouse who gives himself in the Eucharist, is not a question open to discussion, but it can prove especially divisive if sacramental power is too closely identified with power in general.' It is even more divisive if those who reserve to themselves sacramental power determine that they alone can determine who has access to that power and legislate that the matter is not open for discussion. Given that the power to determine the teaching of the magisterium and the provisions of canon law is not a sacramental power, is there not a need to include women in the decision that the question is not open to discussion and in the contemporary quest for an answer to the question? Francis's position on this may be politic for the moment within the Vatican which has had a long-time preoccupation with shutting down the discussion, but the position is incoherent.

No one doubts the pastoral sensitivity of Pope Francis. But the Church will continue to suffer for as long as it does not engage in open, ongoing discussion and education about this issue. The official position is no longer comprehensible to most people of good will, and not even those at the very top of the hierarchy have a willingness or capacity to explain it. As school principals you know that gender inequality is no longer an option.

The claim that the matter 'is not a question open to discussion' cannot be maintained unless sacramental power also includes the power to determine theology and the power to determine canon law. Ultimately the Pope's claim must be that only those possessed of sacramental power can determine the magisterium and canon law. Conceding for the moment the historic exclusion of women from the sacramental power of presidency at Eucharist, we need to determine if 'the possible role of women in decision-making in different areas of the Church's life' could include the power to contribute to theological discussion and the shaping of the magisterium and to canonical discussion about sanctions for participating in theological discussion on set topics such as the ordination of women. As Francis says, 'Demands that the legitimate rights of women be respected, based on the firm conviction that men and women are equal in dignity, present the Church with profound and challenging questions which cannot be lightly evaded.' If they continue to be evaded, the Church's credibility as an exemplar of human rights will be tarnished irreparably.

2. A safe, transparent and accountable post Royal Commission Church

For children to be safe in our schools, for victims to be respected and cared for, and for the reputation of our Church to be restored, we all know that the bishops and clergy cannot do it on their own. In the past, that's been part the problem. You school principals have the expertise, the knowledge, and the passion to put children first. In your midst are great educational leaders like John Crowley from St Patrick's Ballarat who have done the hard yards, sitting down with victims, studying overseas developments, espousing best practice, and reflecting on recent experience in the light of the gospels.

Do not be downhearted. You cannot do this on your own. Our Church cannot do it on its own. We needed the help of the state to put our house in order. We now have the help of the state as we work out together how best to protect all children in our care.

Not for a moment do I want to downplay the disproportionate number of victims who came forward describing abuse suffered in the Catholic Church. But I think it is important and consoling in solidarity for us to bear in mind four things Justice McClellan said on the last day of the royal commission's sitting on 14 December 2017. I set out the key quotes.

'Just over 8,000 people have come and spoken with a Commissioner in a private session. For many of those people, it has been the first time they have told their story. Most have never been to the police or any person in authority to report the abuse. More than 2,500 allegations have been reported by the Royal Commission to the police. Many of these matters came to our attention in a private session.'

'The failure to protect children has not been limited to institutions providing services to children. Some of our most important State instrumentalities have failed. Police often refused to believe children. They refused to investigate their complaints of abuse. Many children, who had attempted to escape abuse, were returned to unsafe institutions by the police. Child protection agencies did not listen to children. They did not act on their concerns, leaving them in situations of danger.'

'There may be leaders and members of some institutions who resent the intrusion of the Royal Commission into their affairs. However, if the problems we have identified are to be adequately addressed, changes must be made. There must be changes in the culture, structure and governance practices of many institutions.'

So when all is said and done, it has to be admitted that in the past, victims did not come forward to police or to other authorities — neither at the time of the offence nor years later when they were adults. In the past, the whole of society was prejudiced against the victims, and going to the police was known to be worse than useless. All this has now changed. There have been many changes for the better — within police forces, within churches etc. What's not changed is this last observation by Justice McClellan:

'This Royal Commission has been concerned with the sexual abuse of children within institutions. It is important to remember that, notwithstanding the problems we have identified, the number of children who are sexually abused in familial or other circumstances far exceeds those who are abused in institutions.'

'The sexual abuse of any child is intolerable in a civilised society. It is the responsibility of our entire community to acknowledge that children are being abused. We must each resolve that we should do what we can to protect them. The tragic impact of abuse for individuals and through them our entire society demands nothing less.'

Even though you be employed by a bishop, it is essential that you offer frank and fearless advice to your bishop on these issues. It was respectful silence from the laity or the presumption that 'Father knows best' that compounded the problems in the past. I had said and written things to bishops in the last five years that I would never have said or written in previous times. This is not Ordinary Time. We are dealing with an extraordinary moment of change in our church. The old-style clerical pyramid has had its day.

In recent days, I have been quite outspoken about the need for Archbishop Wilson to resign. As a lawyer, I think he has very good prospects of appealing his conviction and sentence. But that's not the point. His appeals could take another year or two. Meanwhile he has told the court and the faithful of Adelaide that he is suffering the early onset of Alzheimer's Disease. Whatever of any legal errors made by the magistrate, he has made a fairly unappealable finding that the complainant was honest and reliable in recalling what he said to Wilson when he was a boy and that Wilson was unreliable and not credible. Philip Wilson did great work for the church in cleaning up the mess later when he was bishop in Wollongong and then nationally when he was Archbishop of Adelaide and a member of the Permanent Committee of the ACBC. But that's not the point either.

In view of Archbishop Wilson's decision not to submit his resignation pursuant to Canon 401.2 of the Code of Canon Law which provides, 'A diocesan bishop who has become less able to fulfil his office because of ill health or some other grave cause is earnestly requested to present his resignation from office', it is necessary that we all give closer attention to Recommendation 16.7 of the Royal Commission: 'The Australian Catholic Bishops Conference should conduct a national review of the governance and management structures of dioceses and parishes, including in relation to issues of transparency, accountability, consultation and the participation of lay men and women. This review should draw from the approaches to governance of Catholic health, community services and education agencies.'

During the royal commission, our bishops and the leaders of the religious institutes appointed a competent Truth Justice and Healing Council to monitor and co-ordinate the Church's response to the royal commission. That council included competent laity from differing professional backgrounds, and individuals with quite diverse perspectives. They have now provided detailed reports to the bishops. Those reports include some dissenting opinions. For the good of the Church, it is essential that those reports be published and considered by people inside and outside the Church so that we can assure ourselves that we have done all we can to make our Church fit for purpose in contemporary Australia.

In the months ahead, there will be talk in your school about the trials of Cardinal Pell. And no doubt prayers will be offered. Could I sound one warning note, and provide one suggestion. The warning: Those convinced of Cardinal Pell's guilt don't know what they're talking about. They have not yet heard the evidence. They don't even know who the complainants are. Those convinced of Cardinal Pell's innocence don't know what they're talking about. They have not yet heard the evidence. They don't even know who the complainants are. We have to wait for the legal processes to run their course. The suggestion: when offering prayers in your school or parish, do not pray only for Cardinal Pell. Pray for all those involved in these proceedings, including the complainants. And pray for all the institutions involved – the Church, the police, the legal profession, the court system, and the media. These trials are putting all these individuals and all these institutions on trial. Let's hope and pray that justice is done.

3. School funding

In May last year, I was walking around Parliament House minding my own business, and the business of Catholic Social Services which is my day job. Prime Minister Malcolm Turnbull spotted me and called me into his office to talk about school funding. I then had follow-up meeting with Cabinet Minister Christopher Pyne and Education Minister Senator Birmingham. All three of them insisted that the days of special deals for Catholics are over. I agreed. All three insisted that there was a need to settle on some key principles for fair and transparent school funding. I agreed. All three agreed that it was necessary to ensure that the principles were rightly applied.

I wrote about the issue in Eureka Street. In the original article published on 23 May 2017, I said, 'When it comes to the application of the principles, the Catholic educators are stating two sound principled objections.' I set out the first principled objection in these terms: 'The Australian Bureau of Statistics assessment of the socio-economic score (SES) is very inaccurate as it draws on clusters of households averaging income and education. Also, the government is wanting to abandon the student weighted system average SES. The Catholics point out that especially with low fee-paying primary schools, the parent base, even in better-off suburbs, includes families who can ill afford to pay high fees. Any significant jump in fees will result in many of those families simply shifting their children to government schools, which will then be bursting at the seams. Some of these Catholic primary schools are being expected to increase their fees radically in the next few years because the increased Commonwealth revenue stream will not come on line for another four years.'

On 19 June 2017, I raised the question, 'Is the application of the principles right?' It turns out that it was not. The Chaney Review has now been released. The present SES score methodology first introduced in 2001 and reviewed every five years was found to be deficient. 'The data show that capacity to contribute is not evenly distributed within Census statistical areas and that patterns of school selection mean that the current methodology, while accurate in many cases, materially overstates the SES of some schools and understates that of others.' The Chaney review panel found, 'Based on extensive analysis of the alternatives, the Board concluded that the current approach is no longer the most accurate measure available and a direct measure of parental income is currently the most fit-for-purpose, transparent, and reliable way to determine a school community's capacity to contribute.'

Everyone is agreed that the system would be fairer and the principles more appropriately applied if there could be an assessment of the personal income of each family rather than an averaging of income in a geographic area. Most of the Chaney Panel thought the system would be fairest simply by considering parental income. The dissenting member of the panel, Professor Greg Craven who is vice chancellor of ACU thought there should also be an assessment of each school's income and wealth, with particular attention to the fees charged by the school. The Guardian newspaper has accurately reported that 'Craven suggested that the fact some parents could afford fees of between $20,000 and $30,000 was a fair measure of their capacity to pay, in the same way as a “significant number of Australians' would draw conclusions about the financial capacity of people who could afford to buy a C-class Mercedes Benz Cabriolet at a cost of $95,000'.

For you as Catholic principals, the mantra should be clear. No special deals. Just give us clear, fair principles, and apply those principles transparently and accurately.

4. An inclusive, non-discriminatory society that respects freedom of religion

I voted 'yes' in last year's ABS survey on same sex marriage. As a priest, I was prepared to explain why I was voting 'yes' during the campaign. I voted 'yes', in part because I thought that the outcome was inevitable. But also, I thought that full civil recognition of such relationships was an idea whose time had come. What was needed was an outcome which helped to maintain respect for freedom of religion, the standing of the Churches, and the pastoral care and concern of everyone affected by such relationships, including the increasing number of children being brought up in households headed by same sex couples committed to each other and their children. I thought it appropriate that at least a handful of clergy should come out and, when asked, express their intention to vote 'yes'.

I would draw three distinctions: marriage as a sacrament, marriage as a natural law institution, and marriage as a legal construct of civil law.

Marriage as a sacrament is one of those graced moments in the life of the believing Christian who is a Catholic. As our Catechism puts it: 'The sacraments are “of the Church' in the double sense that they are “by her' and “for her'. They are “by the Church', for she is the sacrament of Christ's action at work in her through the mission of the Holy Spirit. They are “for the Church' in the sense that “the sacraments make the Church', since they manifest and communicate to men, above all in the Eucharist, the mystery of communion with the God who is love, One in three persons.' The sacrament of marriage typically is celebrated by two baptised persons (a man and a woman) who are free to marry, are committed to each other exclusively for life, and are open to the bearing and nurturing of their children from the union.