Filter Content

- From the President

- Ticker ED speak with ACPPA President

- Australian Catholic Super

- SPOTLIGHT - Western Australia

- Australia’s teacher shortage won’t be solved until we treat teaching as a profession, not a trade

- MSP

- Initial teacher education: With the profession in crisis, let’s not waste the chance for change

- 2020 National Catholic Education Conference - Don't Miss Out!

- ASUS Education

- WOODS Furniture

- How to talk to students right now about the most important crisis of our time

- Catholic Schools Guide

- ACP Connect -Have you subscribed?

- Why that one tweet went viral (and what we must do now to fix "teacher shortages")

- Catholic Church Insurance CCI

- It’s great education ministers agree the teacher shortage is a problem, but their new plan ignores the root causes

- APPA National Conference - Registrations now open!

- Enquiry Tracker

- Raised Voices

- Just a Thought!

Dear Colleagues and Members

This week the Directors of our ACPPA Board met in Brisbane for our third meeting of the year. It is so important for us to meet together in person after what has been an unprecedented complex time for schools. As you know this year, we have a number of new Directors and our meeting focussed on establishing how we use our diversity and skills to action our new strategic plan. There is no better way to explore and discuss the national agenda than by sitting around a table with colleagues and entering into deep conversation and discernment.

At this meeting we spent considerable time planning around our new Strategic Plan and heard from our invited guests:

- The key pillars of our plan include Catholic Advocacy, National Engagement and Board Growth and Development and can be now found on our website (see below)

- Dr Debra Sayce, Executive Director of Catholic Education Western Australia shared her thoughts on student wellbeing frameworks, leadership in context, system initiatives and the importance of relationships in all these areas.

- The BE YOU team from Beyond Blue spoke with us about the resources and information available to all Principals around student and teacher wellbeing. Be You is a free federally funded initiative for all schools in Australia.

- A major agenda item was to break into newly formed sub-committees around financial management, member engagement, wellbeing, research, and professional learning. The work of the Board is to ensure we act with due diligence in all areas which affect Principal voice and advocacy. To complement these groups we also created and refined a number of policy frameworks.

- The recent roundtable for the national teacher action plan was high on our agenda as we discussed our ACPPA position and involvement in upcoming talks.

- We shared a presentation with Josephine and Tyson Brennan from Brennan Law, who have co-created ACPConnect with us. We are committed to growing this portal and ensuring we continue promoting the value of this wellbeing portal for all our Principals.

- Look out for the data around our recent annual benchmarking survey. These will be shared though our 'Just the Essentials' fortnightly bulletin.

- A highlight of our time together was to share our Board dinner with ACPPA’s 1984 Inaugural President – Frank Hennessy. Frank was instrumental in forming and shaping ACPPA in the early days and along with his wife Lorraine, enjoyed a night of story and conversation. We also presented Frank with an earlier version of our ACPPA flag as a keepsake.

Our Board work on your behalf to be the voice of Catholic Primary Principals across Australia. Please contact your State/Territory Director (details on our website) for more information.

Enjoy this edition of Talk Of Principals In Catholic Schools.

Take Care

Peter Cutrona

President

DEVELOPING CPPA (WA) ALUMNI

Our CPPA (WA) Project Officer, Shane Baker, was asked to undertake two projects in 2022, one around induction for new principals and the role of a professional association like the CPPA, and the second project was to establish an Alumni for anyone who has served as a principal in Catholic schools here in Western Australia.

After working on both projects for six months or so, it became clear to the CPPA (WA) Executive that both projects are closely linked and aligned in terms of offering support to newly appointed principals, those working in the role already and those who have retired from the role. All three stages are important, and this is the challenge we have set ourselves. This article looks at the progress being made in setting up our Alumni.

MAINTAINING CONNECTIONS BEYOND THE ROLE

In 2022, a small team of past principals have been working hard to construct an Alumni Contact List. The dedicated volunteers have gathered up over one hundred confirmed contacts from our list of 194 serving past principals (since 1976 when the CPPA began). This list includes 18 deceased past principals whom we will remember as honorary Alumni Members.

Alumni membership is free, and the group aim to communicate via email and the development of the CPPA WA website.

BENEFITS OF BEING PART OF CPPA (WA) ALUMNI

These are some of the many benefits that one can derive from being a member of the Alumni:

- The Association exists to do good.

- Friendships, happiness, good times and laughter are all elements of positive wellbeing.

- Networking is important for conversations and stories to be told.

- Belonging to and sharing a common understanding of the job we once performed.

- Our cognitive well-being is encouraged.

- Keeping in touch with the Catholic Education WA network.

- Sharing insights, telling stories, and looking back all help to keep the mind turning over.

- Volunteering and pastoral opportunities.

- Membership is free and simple with no strings.

- Your career and contribution and keeping in touch have a nice synergy – it is meant to be.

- Keeping it together for a purpose makes sense.

- In 2026, CPPA will celebrate 50 years of operation.

OUR PLANS

Proposals for 2022 begin with an inaugural event on August 24 with an Alumni Members Lunch and Catch-up and an invitation to the CPPA (WA) Conference Dinner. Going forward, CPPA (WA) plans to engage the Alumni, which include regular Communication Updates, Alumni meetings in regional and metro areas, an annual Breakfast meeting sponsored by CPPA as well an invitation to the CPPA Conference Dinner each year.

Sue Fox and Fran Italiano - Alumni members Shane Baker - Project Officer

Andrew Colley – Principal

Hammond Park Catholic Primary School

Hammond Park, WA

Australia’s teacher shortage won’t be solved until we treat teaching as a profession, not a trade

5 min read

Larissa McLean Davies, The University of Melbourne and Jim Watterston, The University of Melbourne

Today, state and federal education ministers will meet in Canberra to discuss the teacher shortage.

In their first in-person meeting for more than a year, they will also speak to principals, teachers and education experts about the crisis. Not only do we need more people to take up teaching as a career, experienced teachers are leaving the profession, or saying they plan to.

A recent survey found almost 60% of teachers in New South Wales plan to quit in the next five years.

Ahead of the meeting, numerous solutions have been offered by experts and advocates, including a teaching “apprenticeship”, and fast-tracking students or mid-career professionals in other fields into the classrooms.

As education academics researching the future of teacher education in Australia, we are concerned the current debate is missing the bigger picture.

While well-intended, the ideas on offer address the symptoms, rather than the complexity of the cause. We need a coherent and comprehensive plan to address the real problem: teaching is not being treated like a profession.

A teaching apprenticeship?

Ahead of today’s meeting, Universities Australia proposed a “teaching apprenticeship”. This would see student teachers get to do more time in schools with a job at the end of it.

Research shows it is very important for students to have practical experience. But calling it an “apprenticeship” implies teaching is simply a trade to be learnt on the job, rather than a complex profession that requires university study.

On top of this, getting teaching students to fill the growing shortage of teachers is not addressing the need for qualified teachers to be in classrooms.

This plan also optimistically assumes schools and teachers under pressure will be able to provide the support an increased number of “apprentice” teachers would need. Given universities are already finding it difficult to secure teaching placements, this seems unrealistic.

Fast-tracking to the classroom

Other suggestions include fast-tracking people through their teacher education, particularly if they are coming to teaching mid-career from a different profession.

While we need to welcome other skills and people’s commitment to become teachers, this is worrying.

For one thing, the strategy has not worked in the United States, because it does not address the conditions and unsustainable workloads of teachers. It also discounts teachers’ knowledge of complex teaching methods and approaches.

Teachers need to be able to plan lessons and units, secure good resources for these lessons, engage their students, engage students who need additional support, assess what they have learned, manage behaviour and look after young people’s wellbeing (among other skills).

We would not assume a high-school legal studies teacher, for example, would be able to become a lawyer without undertaking the appropriate tertiary study. So why do we imagine a lawyer can short-cut the education required to become a legal studies teacher?

This strategy implies content knowledge, rather than knowledge of how to teach and how best to teach particular students, is the core business of teaching. It also feeds the unhelpful myth that “anyone can teach”.

So, what is the way forward?

We need solutions that go beyond bespoke schemes and incentives.

The root of this issue is not the quality of education new teachers experience or their readiness to teach. We already have professional teaching standards, standards for teaching courses and entry and exit testing for student teachers. The education of beginning teachers is arguably the most regulated and measured part of the profession.

We know the circumstances that contribute to the teacher shortage are complex and include teacher workloads, the status of teaching and resourcing. So we need solutions that look at the profession as a whole. Here are two big picture approaches to address the current crisis.

1. Teaching must be treated as a profession

Other professions – such as medicine, law or engineering – value expertise, reward the development of new knowledge, and the contribution of those who lead others.

In teaching, there has been so much focus on the initial preparation of teachers (before they are registered and teach independently in the classroom) that we don’t have a “whole-of-career” approach.

Teachers already in the classroom are often reluctant to take on student teachers because it means they have more work and little recompense for it. There is a token amount of money available for it, but this may not go directly to the teacher.

We know mentoring is critical to support teachers and keep them in the profession. So let’s make it a desirable thing to do for all teachers. If you mentor and do it well, this should be recognised through career progression and remuneration.

In professions such as medicine, you develop specialist knowledge and expertise. Or you specialise as a generalist. But in teaching, teachers are largely required to develop expertise in all teaching methods, assessments and all aspects of student health and wellbeing.

If we could rethink the work of teachers, and teachers could specialise in areas they are more interested in and are needed, this would provide them with new career pathways.

2. We need different approaches for different schools

Policies for teachers and their work often assume all education systems across all parts of the country are largely the same.

In a country as diverse as Australia, this is problematic. An analysis of NAPLAN data shows schools can be grouped into five distinct socio-economic bands. This means some schools are more demanding or complex to teach in than others.

We know the impacts of staff shortages, and teachers teaching out of their fields of expertise are more likely to be felt outside capital cities.

If we want to retain excellent teachers in all schools, then we need to acknowledge the demands on those working in rural, remote, and isolated communities are different from metropolitan schools.

Not only do these schools need to adequate resources and funding but teachers working in hard-to-staff schools should be paid and supported accordingly. ![]()

Larissa McLean Davies, Professor of Teacher Education, The University of Melbourne and Jim Watterston, Dean, Melbourne Graduate School of Education, The University of Melbourne

This article is republished from The Conversation under a Creative Commons license. Read the original article.

Read LessMSP Photography are passionate about providing quality, photographic memories for students and families, while making Photo Day as easy as possible for School staff.

Learn more at www.msp.com.au

Initial teacher education: With the profession in crisis, let’s not waste the chance for change

5 min read

Less than two weeks ago, teachers in New South Wales went on strike for just the second time. The previous week, Victoria offered teachers $800 a day – double the usual rate – to teach in regional and rural schools.

Canaries in the education coalmine.

Teachers are critical to society, but the profession has reached a crisis point in Australia, and we need urgent action.

According to a recent study by Monash Education, 26% of the school teachers surveyed plan to leave the profession in the next five years.

Recent Australian Teacher Workforce Data figures reveals enrolments to initial teacher education (ITE) courses dropped 11% in 2019, and continue to drop, while course completions are on the same downward trend.

In regional, rural and remote areas, students would often not be taught unless the principals stepped in to fill gaps, and it’s not uncommon for some schools to combine classes in hallways.

A crisis in the making

Due to particular shortages in some subject areas such as mathematics, teachers are often required to teach outside their specialism.

The combination of high workloads, sometimes punitive accountability regimes, and rising inflation produces fractious industrial relations.

Layer the COVID pandemic over a shortage of teachers and you have an almost perfect crisis:

-

Not enough teachers, especially outside metro areas

-

Variable quality of teaching (inevitable if teachers are teaching outside specialism)

-

Fewer people wanting to enter the profession

-

Plenty of (largely negative) media coverage.

Former education minister Alan Tudge commissioned the Quality Review of Initial Teacher Education, published just before the federal election. While it contained several important recommendations, it perpetuated one of the key myths that bedevil attempts to improve ITE programs – everything depends on what’s taught in the university.

Little or no attention is given to what happens in schools when politicians seek to “reform” ITE.

Yet we’ve known for decades that the effects of even the most evidence-based university ITE curriculums get “washed out” in practice. This is hardly surprising.

In times of teacher shortages, governments often seek to “fast-track” career-changers into the job market. The results are often predictable – intensive (or just intense) programs can burn out the prospective teacher before they can acclimatise to schools.

Read more: “I wouldn't be where I am today”: Recognising the outstanding work of teachers

The issue, for career-changers, is not how fast they qualify, but how they support themselves financially while learning to teach.

ITE policy in Australia – as in many other countries – has tended to focus on the individual student teacher, and the expectation that they navigate transitions between the university and one or more schools, on “placement”.

The school “hosts” the student teacher. From a distance, the university tries to support their learning.

The boundary between university and school becomes what psychologist King Beach called a “consequential transition” – a powerful but very high-risk opportunity for learning.

A radical rethink is needed

It’s time to think radically about how we prepare teachers. Thinking differently is essential both in terms of teacher supply and teaching quality.

That means shifting focus from the individual teacher to the school. How can the school become both a safe and a supportive place to work and learn for teachers? How can the education and training of new teachers align with the school’s own development plans, improving both the supply of teachers and the quality of their teaching? And, crucially, how can the school retain teachers?

The retention of teachers is even more important than the supply of new ones in the current crisis for at least two reasons. First, it’s an incredibly inefficient use of scarce resources to burn out teachers; second, generally, teachers get better in terms of teaching quality, especially in the early career.

Focusing on the school as a whole and helping to create a sustainable environment for teachers to thrive is a long-term aim requiring active collaboration between governments, teacher unions, principals, community organisations, as well as universities.

It’s not a pipe dream. Active collaboration is the norm in some countries, as I observed working with the Norwegian government on its 2017 ITE reforms.

A window of opportunity

A change of federal government in Australia presents an opportunity in this crisis.

In terms of ITE, there’s evidence that innovative approaches that centre the school and foster links between ITE as an activity and school development can address both teacher supply and teaching quality.

The US teacher residency model for graduates has been federally funded since the Obama administration. Graduates – employed as “residents” in schools alongside completing academic coursework – make good teachers and stay in their schools post-qualification.

A distinctive feature of teacher residencies is that a school’s overall development is being fostered by the whole-school attention to teachers’ learning.

Talk of “partnership” is common when referring to university-school relations. Unlike “partnerships”, though, residencies don’t share out different tasks; residencies are a shared activity involving numerous stakeholders.

Placing the school at the centre

ITE – particularly faster ITE – will not solve that crisis. At Monash Education, we believe this is the time to think radically about postgraduate ITE. To think in ways that centre the school as a safe place to work and learn; with student teachers employed as residents, their work in classrooms part of the curriculum, co-designed with schools; drawing on the research expertise of the university; and respectful of the knowledge and perspectives of the schools’ communities.

Initially, we want to focus on rural and regional schools – schools sometimes referred to as “hard to staff”; schools where a new way of both preparing and retaining teachers is likely to have the most impact.

So, we’re beginning with a summit for principals. Everything on the table. No defensiveness about what we at Monash could do better; an invitation to rethink business-as-usual in schools and the university.

Wish us luck.

This article was first published on Monash Lens. Read the original article

Read Less

2020 National Catholic Education Conference - Don't Miss Out!

The 2022 National Catholic Education Conference is less than six weeks away if you haven't registered already, now is the time!

Attend in-person at the Melbourne Convention and Exhibition Centre or virtually.

Day registrations are also available!

DON'T MISS OUT - 2022 NATIONAL CATHOLIC EDUCATION CONFERENCE (mailchi.mp)

How to talk to students right now about the most important crisis of our time

5 min read

With the recent release of the Australia State of the Environment report and the IPCC 6th Assessment report, there is mounting evidence that climate change is already having drastic impacts on the planet and will fundamentally change our way of life in the future.

Bringing the crisis into the classroom

Charlotte Jones: Young people are aware of these facts of climate change and are expressing overwhelming concern. Furthermore, young people, like us all, are already living with the dire impacts of climate change such as extreme weather events including 2019/20 Black Summer Fires.

In response, many young people are taking actions – changing consumer choices, striking from school (more recently through online strikes), talking with MPs and taking litigation action.

At the same time there have been growing demands from students, parents and academics, to bring climate change more prominently into education curricula. This presents important opportunities to address existential issues of our time and to prepare young people for climate changed futures.

However, as we bring climate change into the curricula, we need to pay attention to the emotional significance this has for students, with many young people experiencing legitimate and increasing anxiety as they grapple with climate change.

So, what can we learn from young people’s experiences as we bring climate change further into the classroom?

Our research involved talking with young people (18-24 years) about their educational experiences of climate change when they were at school. We asked them to describe, reflect upon and interpret their educational encounters with climate change, and their emotional responses to climate change during schooling, including any ongoing significances of these in their early adulthood. Three key themes emerged.

1. Stripped of power

For many students learning about climate change left them overwhelmed by information and by experiences of limited agency and power. Climate change knowledge was fragmented and divided by disciplinary boundaries. Students were not supported to navigate the boundaries between school and life and were left feeling helpless before this unfolding emergency. The home/school dichotomy was reflective of the public/private dichotomy of emotion, with emotions about the climate crisis, for many, discouraged in formal education spaces by their teachers and peers. While some students sought to maintain this distance, others were paralysed by it.

2. Stranded by the generational gap

Learning about climate change alerted many students to their positions in a system of unequal power. At the time of learning about climate change they couldn’t vote and had limited ability to change their consumer choices or their mode of transport – and yet they learnt that these very actions are powerful tools to respond to climate change. Adults by contrast can undertake these actions and are positioned in our society as protectors and guides. However, for many of these participants learning about climate change sparked feelings of betrayal, as adults failed to fulfil these promised roles. Their security in adults, for many, was lost during these learning experiences as they grappled with a lack of intergenerational climate justice.

3. Daunted by the future

For many, the jarring reality of climate change conflicted with ideals of a stable and secure future. Students felt ill-equipped to cope with the future climatic instability they had just learnt about. Anxiety about instability, and grief for lived and anticipated loss, were deeply felt by many (often in private) and changed how students perceived their personal and global futures. Hope, however, was experienced in various ways – hope in action, in technology, in religion, in humanity – and was experienced in entanglement with other emotions.

Bearing witness to emotions

These experiences present a snapshot of the formative experiences of climate change education and offer key learning for educators as we bring climate change into school curricula. These stories make clear the need for fostering safe and facilitative spaces for young people to respond to learning about climate change through their full range of cognitive, bodily and emotive registers. Young people are beginning to be louder in initiating these spaces and are demanding places for these conversations. Educators, parents, politicians and others need to be active in responding to this need and in creating and fostering spaces alongside young people that give social permission to experience and express emotions about climate change.

Acknowledge and empower

Cristy Clark: There are several important things to remember when talking to university students about the environment. The first is that they are already hyper-aware of their intimate relationship with the environment, and of the ways that climate change is affecting their lives and their futures. The second is that this is an issue that most of them feel very passionate about. Finally, the environment is relevant to every subject we teach.

I teach law, and the environment forms the background to all of the subjects that we engage with. In Property Law, this means that students learn about the role of our property law system in commodifying land and entrenching an extractive approach to the environment, while also learning about First Law and the relational approach to land embedded in the obligations to Country that it recognises. It doesn’t take much for students to note the imperative to decolonise our property law system in the face of the destructive ecological and social impacts of our settler-colonial framework. They have grown up witnessing these impacts and are already open to alternative approaches.

Similarly, I have never seen my human rights law students more passionate than when they worked on the right to a healthy environment. They spoke about living through the horror of the Black Summer Bushfires, as thick acrid smoke filled the air and Canberra became, for a time, the most polluted city on earth. Students were also quick to grasp the link between human rights and the environment - its foundational role in realising the rights to health, life, water and livelihood; and the specific relationship that it shares with the right to culture for Indigenous peoples.

Finally, when studying emerging jurisprudence around so-called ‘rights of nature’, students moved quickly from scepticism to acceptance, as they learned about the wide range of jurisdictions around the world recognising the rights of natural entities, such as rivers. Once again, they were quick to intuitively grasp our interdependence with the environment - that we are part of nature and cannot afford to continue to treat it as a resource that exists solely for our benefit. In this context, the tensions and potential synergies of these developments with First Law raised complex questions around ontologies (the ways we categorise things and the relationships between them) and epistemologies (theories of knowledge), but the students were more than up to the challenge and keen to grapple with these issues.

The environment affects every aspect of our lives and every subject we study, and students are intimately aware of the pressures that it is under and the existential threat posed by climate change. In the face of these realities, the only ethical thing we can do is to acknowledge this reality and empower our students to play a role in solving the climate crisis - whether through law reform, human rights litigation, or in any other profession such as education, science, and health. The very last thing they want is to be expected to passively sit by while those in charge continue to squander their futures.

Charlotte Jones is a social scientist and current PhD Candidate in the School of Geography, Planning, and Spatial Sciences at the University of Tasmania. Her research focusses on the emotional significances for young people, and how this shapes their relationships and orientations towards personal and planetary futures.

Cristy Clark is an Associate Professor of Law in the Faculty of Business, Government and Law at the University of Canberra, Australia. Her research focuses on legal geography, the commons, and the intersection of human rights, neoliberalism, activism and the environment.

This article was originally published on EduResearch Matters. Read the original article.

As Australia’s leading Catholic Schools website directory, we’re offering every Catholic Primary School a FREE upgrade for 2022 and 2023.

Every Catholic School in Australia has a listing already – why not make your primary school stand out with some images, and a little more information?

Step 1: Check out your current free listing at Catholic Schools Guide

Step 2: Request your free upgrade

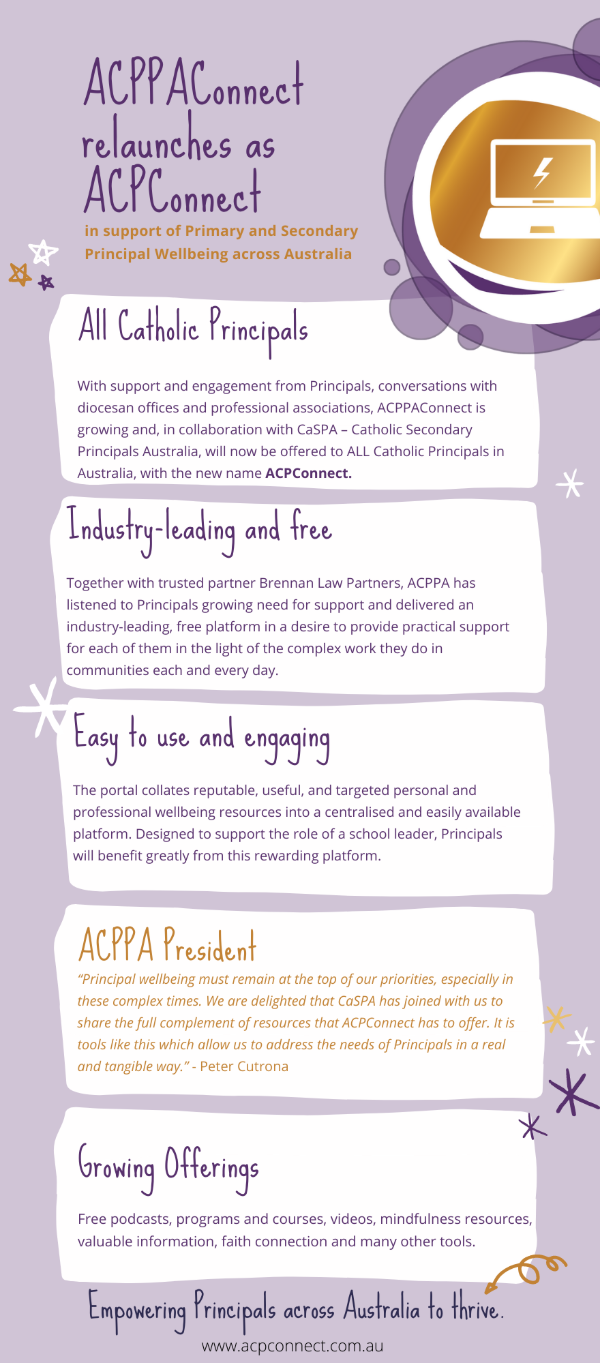

ACP Connect -Have you subscribed?

The Australian Catholic Primary Principals Association (ACPPA) with support from Catholic Secondary Principals Australia (CaSPA) presents our Principal Health and Wellbeing portal for practising Principals– ACPConnect

Originally launched in 2020, ACPPAConnect was only for Primary Principals, but now we have also made it available to our secondary colleagues as ACPConnect.

Watch the video here:

Once subscribed you will recieve regular updates about new resources.

Email ACPConnect (hello@acpconnect.com.au) to access your FREE online account. If you don’t see this email, please check your junk mail. If you still haven’t received it, please let us know.

Contact hello@acpconnect.com.au OR paul.colyer@acppa.catholic.edu.au

Why that one tweet went viral (and what we must do now to fix "teacher shortages")

Nearly all these comments were posted by teachers or ex-teachers who emphatically agree that a change is needed in how we frame “teacher shortages”. These comments were from all around the world, mainly from the US but also from Australia, Canada, the UK and elsewhere. I haven’t yet sifted through all the comments, which keep on coming.

Overwhelmingly, these teachers (or ex-teachers) perceive the discourse of “teacher shortages” as misguided and even hurtful. As they point out, there are thousands and thousands of well-prepared, passionate, skilled, knowledgeable teachers. Comments on the original post recount how much they put into their teaching, how well qualified they are yet how little they felt valued. The constant criticism of teachers is something Nicole Mockler has written about recently, in her review of media representations of teachers.

Those who posted explained how much they loved the kids in their classrooms, created and taught creative, content-rich lessons. Many said they had been fully planning to teach for the rest of their lives. In other words, there was never a ‘shortage’ of good teachers who might have stayed had it not been so hard. They grieve their loss of career. Many say they didn’t really want to leave teaching, but as widely reported, they could just no longer teach how they wanted to - nor in some cases could they maintain their mental and physical health under current conditions. Teachers talked about the pressures of only ever receiving impermanent contracts, of endless reporting, of unreasonable workloads dominated by non-teaching tasks, of being on the receiving end of constant teacher-blaming. They also wrote about the de-professionalisation of teaching and their loss of autonomy.

Some mentioned other reasons for leaving, such as poor student behaviour but by far the majority of comments simply responded ‘truth’ or ‘yessss’ or ‘agree’. The sadness on the part of teachers who no longer feel they can remain teaching is palpable from these responses.

Some teachers who have left the profession have found a way around those pressures by taking advantage of government schemes, both in Australia and elsewhere that are designed to address teacher shortages but may have created a different set of problems. For instance, in Victoria significant funding has been allocated through the Tutor Learning Initiative https://www.vic.gov.au/tutor-learning-initiative-2022-information-for-prospective-tutors which employs part-time tutors in schools to ‘catch up’ students who are academically behind since the pandemic. One unintended consequence was that exhausted and often very experienced teachers took the opportunity to take well-paid tutoring jobs that relieved them of the parts of teaching they liked least, such as duties that could be carried out by administrative staff. Again, the ‘resignation’ from teaching cannot be perceived as a ‘teacher shortage’ but as a kind of redistribution of talent. Good or ‘quality’ teachers have chosen to move sideways (in fact downwards, taking less pay and security but with less stress) to stay in schools.

In fact, there is no lack of research on why teachers leave. There have been numerous teacher attrition and retention studies over a great many years. Except for pandemic related workforce issues (sickness and lockdowns) we’ve been warned for a long time that we needed a teacher workforce renewal strategy, not just because of an ageing workforce but because of the increasing accountabilities and pressures on teachers. These issues are widely reported, not just by other researchers, but in recent reports such as the Grattan Institute report Making Time for Great Teaching.

Along with Amy McPherson, Bruce Burnett and Danielle Armour, our recent review of twenty years of government, ITE and private initiatives to attract and retain a teaching workforce conservatively found 147 government, ITE or partnered initiatives that have been trialled over the past twenty years. One recommendation is that understanding the retention of teachers at key ‘walking point’ moments would assist policymakers in designing longer-term, more impactful interventions to attract teachers towards hard-to-staff schools (especially when they are considering leaving the profession).

This review of the many initiatives that have already been funded and implemented is just one research project repeating what seems to be clear. Incentives may attract people including career-changers, to teaching, but it’s a whole of system issue. The problem isn’t Initial Teacher Education on its own, which has been graduating very good (sometimes great) teachers for many, many years. The problem isn’t a lack of smart, passionate, and committed people who want to be teachers. But the well may go dry – we can’t keep looking elsewhere for teachers if we aren’t able to keep them in the profession. There’s little question that this is a crisis. We do need teachers in front of students; and there is no doubt teaching workforce issues are urgent. But sending teachers our there more quickly or prescribing curriculum to ‘help them manage their time’ is a misunderstanding of what’s going on. And by the way, school leaders agree. There were many comments from Principals as well.

I want to make it clear that I had not expected this post to go viral. I have been coordinating social justice teacher education programs such as the Nexus alternative pathway into teaching for a very long time . I see amazing schools and dedicated teachers ever day who are doing remarkable things under difficult circumstances. I am ‘for’ teachers and schools.

If 229.5K isn’t evidence enough of how teachers are feeling I’m not sure what is. I’m also very reluctant to focus only on “teacher grief”. Let’s also tap into the stories of teachers who remain in schools, especially now. Let’s find out what their working lives are like. Their lived experience will tell us how close they are to walking, why they stay, what keeps them going. Nobody knows how to find solutions better than those most affected.

On August 8, the Minister for Education Jason Clare published the Teacher Workforce Shortages Paper in advance of the Teacher Workforce Roundtable to tackle the national teacher workforce shortage

Maybe we should stop using the term teacher shortages.

We have a teacher workforce issue without a doubt. We need more teachers urgently. But some of us are nervous about recruiting new teachers at the same time as we are sorting out their workplace conditions.

Jo Lampert is Professor of Social Inclusion and Teacher Education at La Trobe University. She has led alternative pathways into teaching in hard-to-staff schools for over 15 years, most recently as Director of the Commonwealth and State supported Nexus M. Teach in Victoria, a social justice, employment-based pathway whereby preservice teachers work as Education Support Staff prior to gaining employment as paraprofessionals (Nexus). She tweets at @jolampert.

This article was originally published on EduResearch Matters. Read the original article.

5 min read

Pasi Sahlberg, Southern Cross University

Last Friday, Australia’s state and federal education ministers met with emotional teachers, who spoke of working on weekends and Mothers’ Day to cope with unsustainable workloads – and how they were thinking about leaving the profession.

This was part of their first meeting hosted by the federal minister Jason Clare. The top agenda item was the teacher shortage.

The issue has certainly reached crisis point. Federal education department modelling shows the demand for high school teachers will exceed the supply of new graduate teachers by 4,100 between 2021 to 2025.

Meanwhile, a 2022 Monash University survey found only 8.5% of surveyed teachers in New South Wales say their workloads are manageable and only one in five think the Australian public respects them.

Ministers say they are working towards a plan to fix the crisis. But are they addressing the right issues?

What happened at the meeting?

On a positive note, all ministers agreed Australia has as problem and it is national one. As NSW Education Minister Sarah Mitchell said, “no matter which state minister would be speaking to you […], we’re all dealing with the same issues and challenges”.

Clare told reporters the ministers had tasked their education departments to develop a national plan to address the problem. This will be brought back to the ministers’ next meeting in December for tick off.

The “National Teacher Workforce Action Plan” will focus on five areas: “elevating” the teaching profession, improving teacher supply, strengthening teaching degrees, maximising teachers’ time to teach, and a better understanding of future workforce needs.

In the post-meeting press conference, Clare particularly emphasised the need for more opportunities for student teachers to get practical experience, more focus on how to teach maths and English and encouraging more teachers to mentor their colleagues.

Key questions are missing

Before the election, Labor promised to fix teacher shortages by attracting high-performing school graduates into teaching, paying additional bonuses to outstanding teachers, and importing experts from other fields to teaching.

Not surprisingly, these same ideas appear in the media release for the forthcoming national action plan.

But together Labor’s ideas and the new national plan don’t adequately address the root causes of teacher shortages: unproductive working conditions and noncompetitive pay.

One priority in the proposed new plan is to “maximise” teachers’ time to teach. In fact, Australian teachers already teach for more hours than their peers in other OECD countries.

What would improve teachers’ working conditions is not more time to teach per se, but enough time to plan and work with their colleagues to find more productive ways of teaching.

Workload is the most common reason for intending to leave the teaching profession. In the 2022 Monash University survey, teachers reported their workloads were intensifying and difficult to fit into a reasonable working week. This is due to overwhelming administration, reporting and paperwork for compliance purposes.

The detail we have so far from ministers is silent on how to fix current teacher workloads.

What about pay?

Another reason for teacher shortages is non-competitive pay, especially when it comes to salary progression over a teaching career.

So far, ministers are talking about “rewarding” high-performing teachers. International studies show unexpected things can happen when teachers strive for “excellence” to receive monetary bonuses. Performance-based pay can lead to declining creativity and collegiality in schools when test scores become the dominant driver of teachers’ work.

This also takes away from the main issue. Instead of paying some teachers more, every teacher in Australia deserves fair compensation that reflects the work they do.

A plan to have a plan

Australia is a Promised Land of action plans and working groups. But we are not so good at implementation.

For example, we have declarations and reviews about what school education should be (the Mparntwe Declaration), how schools should be funded (the Gonski Review), and what rights our children have.

But we struggle to turn these into practice. There is a real risk the new “National Teacher Workforce Action Plan” will just see more good intentions and little concrete action.

Australia can learn from other countries

The good news is, Australia is not alone. The United States and England have suffered from chronic shortage of teachers in their schools for some time.

Even in Estonia and Finland – the OECD’s highest-performing countries in education – teaching is not as attractive profession as it used to be. So, there is an opportunity to learn how other countries deal with the teacher workforce challenge.

Every year since 2011 the OECD and Education International have organised the International Summit on the Teaching Profession with the world’s top-performing education systems. Here education ministers and education leaders from 20 countries explore current issues in the teaching profession. Collaboration between ministers and teachers’ unions is the key principle of the summit.

Australia has been invited to these summits since 2011 but has never attended. So, a decade of opportunities to work with other countries has been wasted.

But it is not too late, Clare could attend in the 2023 summit that will be held in Washington DC. Not only to see what others do, but to learn what might be improved in governments’ action plan and teacher policies.

This is what all “education nations” do. Why don’t we?![]()

Pasi Sahlberg, Professor of Education, Southern Cross University

This article is republished from The Conversation under a Creative Commons license. Read the original article.

Read LessAPPA National Conference - Registrations now open!

APPA NATIONAL CONFERENCE 1-4 NOVEMBER 2022 – SYDNEY

The Sydney APPA National Conference for 2022 will be a rich professional learning and collaboration opportunity for educational leaders in primary schools across the nation.

Location: Sofitel Wentworth Hotel, Sydney

Dates: Tuesday 1 November to Friday 4 November 2022

Registrations NOW Open

Don’t miss out on this opportunity to engage both face to face and online to reCONNECT, reENGAGE, reIMAGINE

Need help growing and managing your enrolments? Discover why 60 Catholic Primary Schools are using this easy-to-use solution to increase enquiries and grow enrolments. Enquire now to learn more.

Young Australian students used the Australian Catholics Young Voices Awards to make the point that media can be used for good.

Congratulations to the winners of the 2022 Young Voices Awards, brought to you by Australian Catholic University. Australian students used various media to advocate on behalf of the marginalised, the dispossessed, the aged, the young, and the environment.

JUNIOR WINNERS

ARTICLES

Winner: Hannah Cook, ‘A picture is nothing like the real thing – don’t let life scroll by’, Year 5, Orana Catholic PS, WA

Highly Commended: Lucas Chen, ‘Behind the screen’, Year 6, Don Bosco PS, Vic; Cartia Kotzapanagiotis, ‘The dangers of the internet’, Year 6, Genazzano FCJ, Vic; Nadia Bonekamp, ‘Media gives a voice to voiceless people’, James Gray, Will you help?’, Eleanor Keeler, ‘Help just one’, Michael Monisse, ‘How social media can positively influence people’, and Lucy Phillips, ‘Ringtail rescue’, all Year 6, from Leschenault Catholic PS, WA; Eloise Mikkonen, ‘The power in being diagnosed, Year 5, Loreto Kirribilli, NSW; Eva Delavande Vasconcelos, ‘You matter, I matter, we matter’, Year 5, St Anthony’s, Clovelly, NSW; Hannah Mackellar, ‘Celebrate being You-niquely You’, Harry Hillard, ‘Good News, where are you?’, Daisy Owens, ‘Like, Follow, Connect’, Anna Kavanagh, ‘Will the media save the environment’, Eleonor McConkey, ‘Stars of Service’, Oliver Cruz, ‘Kindness overtakes tragedy’, and Shloka Tummala, ‘Back to the past: the pros and cons of technology, all Year 6, from St Joseph’s PS, Merewether, NSW; Michael Boru, ‘My culture’, Year 6, St Mary’s, Vic; Torah Chapman, ‘Climate can’t wait!’, Year 5, St Michael’s PS, Traralgon, Vic; Ella Falzon, ‘Radical reptile resources’, Matthew Molinar, ‘The vast learning videos on the immense Internet’, Owen Monares, ‘How Youtube can be used in many positive ways’, Gabriella Rinaldi, ‘The dog with a seesaw and Instagram page’, and Abigail Whiting, ‘Recognise women’s sport in the community, all Year 6, from Trinity Catholic Primary, Kemps Creek, NSW.

PHOTOGRAPHY

Winner: Emma Harris, ‘Free Speech Matters’, Year 6, Genazzano FCJ College, Kew, Vic

Highly commended: Angelina Hanna, ‘At the same rate’, Year 5, Our Lady’s Catholic PS, Craigieburn, Vic; Tom Carney, ‘Is there someone to love me?’, Angus Green, ‘The lonely waters’, and Louis Wilson, ‘The waves fight back’, all Year 6, from St Joseph’s, Merewether, NSW; Eva Trubiano, ‘Lockdown’, Year 6, St Oliver Plunkett PS, Pascoe Vale, Vic; Alexis Teuma, Disaster of online and offline bullying’, Year 6, Trinity Catholic Primary, Kemps Creek, NSW.

DIGITAL

Winner: Stephanie Gauci, ‘Change the way you game!’, Year 6, St Oliver Plunkett PS, Vic

Highly commended: Hannah Ellard, ‘Hannah’s talk show!’, and Zoe Guan ‘Pandemic crisis’, Year 6, from Genazzano FCJ College, Vic; Archer Kingm, ‘Social media – a positive spin’, Year 6, Leschenault Catholic PS, WA; Violet Beletich, ‘War in Ukraine’, Eliza Biddle, ‘Homeless awareness’, Francesca Cade, ‘Care for kids’, Eloise Christian, ‘Mental health for children’, Mackenzie Greet, ‘Rescue dogs’, Phoebe King, ‘Podcast on the environment’, and Lucy Matthews, ‘Environment oh environment’, all Year 5, Loreto Kirribilli Junior School, NSW; Emma Webster, ‘Friendship fires’, Year 5, Our Lady Help of Christians, Qld; Stella Radich, ‘Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander voices’, Year 6, Our Lady of the Way, Qld; Alexander Toma, ‘Pollution’, Year 5, Our Lady’s Catholic PS, VIC; Max Miller, ‘Eating to save the Earth’, Year 5, Sacred Heart Catholic School, Tas; Uasi Tuipeatau. ‘Break his legs Cody’, Year 5, St John the Apostle PS, Florey, ACT; Amelia Duncan, ‘Living with adversity’, Year 5, St Josephs, Clare, SA; Sophia Bernleitner, ‘Media: good or bad?’, Year 6, St Therese’s Catholic PS, Denistone, NSW; Lukas White, ‘Mother Earth calls for help’, Year 6, St Therese’s PS, NSW; Ava Spain, ‘It’s Women’s Rights’, Year 6, St Thomas More’s PS, Qld; Liam Clydesdale, ‘Endangered’, Zenon Griffiths, ‘Global warming’, Isaac Moran, ‘Disability in sport’, and Teddy Pasvolsky, ‘War’, all Year 6, St Joseph’s PS Merewether, NSW; and, Alyssa Micallef, ‘Men and women are all the same. Please stop playing this discrimination game!’, Year 6, St Peter’s Primary, Vic.