Filter Content

- From the President

- ACPPA National Survey QUICK CATCH ONLY

- Australian Catholic Super

- Wellbeing Webinars a hit! Did you make time for yourself!

- A message for our Principals from Headspace

- Will the Quality Time Action Plan reduce teacher workload?

- WOODS Furniture

- Caritas Australia School Update

- Why we must talk about teacher professionalism now

- Catholic Church Insurance CCI

- Playground duty really is quality time: how joyful learning happens outside the classroom

- MSP

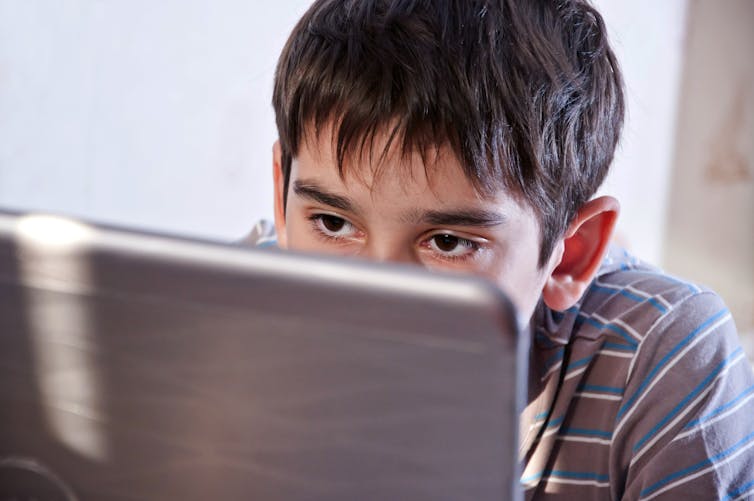

- A new study sounds like good news about screen time and kids’ health. So does it mean we can all stop worrying?

- Switch Education

- Supporting Children through Change and Uncertainty

- Worth a look!

- Counselling conundrum: How school psychology services have coped with COVID

- The Value of Classroom Coaching

- Just a Thought!

Dear Colleagues

It was greatly appreciated to see a good representation of Principals from across the country join us for our recent virtual AGM. At this meeting an amendment to our ACPPA Constitution was passed which will allow State and Territory Associations to become a Branch of ACPPA for a range of reasons including size, finances, and viability. This move will offer support for smaller associations if they choose, and give a greater stability to the work of each Association across Australia. The amended 2021 Constitution can be found on our website.

It was wonderful to acknowledge our valued partners who have continued to support us even during this very difficult year which has impacted each of them in some way. I encourage you to connect with our partners and give them the opportunity to promote their products and services to you and your schools. Without their strong support we would not be able to achieve what we do each year.

It was also nice to receive thanks from our Associations for the steps ACPPA took in 2021 to reduce affiliation fees in response to the impacts of the pandemic.

During our last Board meeting for the year, our Directors spent some considerable time in both reviewing and renewing our strategic plan. We are now in the process of creating new priorities and goals for the 2022-2024 period to ensure we are meeting your needs in both action and advocacy for Catholic school leaders across Australia.

As you have seen we have delayed our national benchmarking survey until 2022 due to the pandemic. However, we encourage you to answer 3 simple questions to keep us focussed on the task. Details are below and I urge you to support us in this way.

Congratulations and thanks to all of you who participated in our Initial Teacher Education (ITE) research project this year. Despite the pandemic we were able to reach far and wide in our consultations and are now preparing a report to the Board, ACU, UNDA and the NCEC later this month. We will disseminate the main findings to you all in the new year.

It was also great to see Principals interested and participating in our Wellbeing webinar series that took place in October. We have received really positive feedback which is included in an article in this journal. Our thanks to our Premium Partner, Australian Catholic Superannuation and SuperFriend, who worked with us to create a bespoke presentation for our leaders. We are now looking at new support initiatives for 2022.

Lastly, I am stepping down as President of ACPPA at the end of the year after 4 years in the role and moving into a leadership role in the Canberra/Goulburn Diocesan office next year. Peter Cutrona, one of our current Vice Presidents, has been elected the new President of ACPPA for the next 3 years. Peter is a Principal in Western Australia and has been a strong advocate of the Western Australian Catholic Primary Principals' Association. This appointment is a good indication of our truly national footprint and brings with it both new opportunities and ways of operating. Congratulations, Peter.

I truly appreciate the dedication and contributions of the ACPPA Board of Directors. These school leaders give their time, energy and advice for the benefit of over 1240 ACPPA members, attending meetings each term, as well as, advocating for their state or territory, representing ACPPA at state and territory meetings, speaking with the media and attending other important functions and meetings.

I would especially like to thank Paul Colyer, our Executive Officer, and Karyn Prior, our Operations Manager, for their support, determined commitment and hard work.

I have been involved with ACPPA for nearly 10 years and I am proud of what the association has achieved in recent years. I have witnessed firsthand the incredible work ACPPA has done to support Principals and to raise the profile of our association across all sectors.

My involvement with ACPPA has been some of the most rewarding professional learning anyone could ever participate in and I have had the opportunity to meet and work very closely with outstanding leaders from across the country. I will be forever grateful for the opportunities ACPPA has provided me professionally and personally, and will certainly miss the national scene, the work, the collegiality, the humour and the social aspects of gathering when we could.

I wish Peter and the future ACPPA Board every success in the future.

‘So that you may prosper in all you do and wherever you go.’

1 Kings 2:3

Kind regards

Brad Gaynor

President

ACPPA National Survey QUICK CATCH ONLY

Due to the difficult year faced by educators, ACPPA has decided to delay our Annual survey until March 2022.

BUT...in order to be able to continue to TAKE THE PULSE, please answer these 3 quick questions NOW! Just click the image or the link below!

Wellbeing Webinars a hit! Did you make time for yourself!

ACPPA, in association with our Premium Partner Australian Catholic Super and SuperFriend have just finished delivering 3 awesome webinars over 3 weeks around Principal Health and Wellbeing.

Professionally and energetically presented by Sandra Surace from SuperFriend, participants were given practical and useful tools in the 5 ways to wellbeing toolkit.

We hope to be able to deliver further great initiatives in 2022 around caring for your mental health.

Some great testimonies from those who particpated:

"I had signed up for the webinar and was wondering about attending (prioritising this over other) until a colleague who attended last week said it was the best hour on this subject. So needlessly to say I fit it in today’s schedule. What did I discover? It was the best hour I’ve spent on the subject. I found it easy listening, compelling and practical enough to do something immediately for my personal wellbeing.

I particularly enjoyed the 40sec clip at the end, summed up the presentations core 5Ws2W in a fun and memorable way! Drilling holes in the plastic container is an effective image. I am going to use the clip, & beyond using this, share the 5Ws2W and the booklet too. If the webinar if offered again I am promoting it to my colleagues in and beyond my diocese."

Jo Scott-Pegum Principal

St Patrick’s Primary School Bega NSW

"The presentation was both reassuring and challenging in many respects. Giving myself time to reflect on my wellbeing and that of my colleagues must always be a priority. The presentation was well researched and delivered by an experienced educator and practitioner in a very engaging way."

Dr Stephen Kennaugh Secondary Principal

St Andrews College Marayong

"I found the webinar today contained a very practical, well researched approach to wellbeing. We were provided with set of easily accessible resources. Sandra's presentation of the 5 Ways framework gave me a way to easy way to think about the key aspects of wellbeing and it caused me to reflect on how effectively I was applying these personally and as a leader of wellbeing."

Mark Bateman - Principal

St John's Primary Narraweena

Contact Paul Colyer for further information if interested in finding out about these sessions for your school.

Paul Colyer - Australian Catholic Primary Principals Association

Phone: 0478973767

Email: paul.colyer@acppa.catholic.edu.au

A message for our Principals from Headspace

I’m writing this as Australia celebrates World Teachers’ Day, and I believe that now more than ever, the contribution of educators and school leaders needs to be recognised and celebrated. Whilst I believe there has been overuse of terms such as “unprecedented”, the previous 18 months has fundamentally changed the way we work, travel, teach and lead school communities.

I’m conscious that there is a vast difference in the experience of schools and leaders across the States and Territories – in May of last year, only three percent of Victorian students were in attendance onsite, while the Northern Territory has returned to 79 percent. However it was experienced in your State or Territory, it is clear that COVID impacted educator wellbeing, whilst changing how educational technologies are utilised, and how student needs are supported. In addition, we now have children in our classrooms who have experienced, and who are trying to make sense of, a global pandemic and the associated uncertainty.

With so much change and challenge to the past year and a half, how can educational leaders mark the end of the school year, and draw some aspects to a close?

Why mark the end of 2021?

Neuroscience now allows us to understand that if we remain in a state of reactivity (fight or flight) for long periods of time, it can contribute to increases in stress hormones, which can impact our sleep quality, blood pressure, and overall physical and mental health. It could be argued that 2020 and 2021 were times which required educational leaders to be highly responsive to rapid changes in how schools operated, and how children were supported to learn. However, periods of high stress are not sustainable if we are to function to the best of our ability. Hence, I would argue that it’s vital that educational leaders use the end of this school year to “mark” an end point to the past 18 months. In doing this, I am conscious that this in no way guarantees that 2022 will be a return to “normal”, or that there won’t be any periods of stress or rapid change. Rather, I invite you to consider that 2022 will not simply be “more of the same”. It is, rather, an opportunity for a fresh start. With this in mind, I encourage you to consider the end of the year as a chance to:

- Reflect on things you have learnt about yourself, and about your school community - Create a space to be future focussed, and consider what matters to you as a leader and an educator

- Create opportunities for connection and conversations about the future of education with your staff

What might this look like in practice?

Reflective practice may come more naturally to us as part of our educational practice, but existing skills and habits of reflection can benefit us at a year’s end. Whether it’s through journaling, reflective discussions with colleagues, family or partners, or with a qualified mental health worker, I invite you to consider the following:

- What do I want to continue doing in 2022 – as a leader? As an educator?

- What do I want to leave in 2021? Why do I want to leave it here?

- What have I been grateful for this year? How have I acknowledged and thanked myself for the year’s work I’ve done?

- When did I demonstrate resiliency?

- What did I learn about home and work boundaries?

I hope that a reflection on 2021 is a useful exercise and may provide an opportunity for your wider staff to begin similar practice. No matter what the end of your school year holds, I would like to thank you for your courageous and compassionate leadership of Australia’s Catholic Primary Schools. Headspace Schools and the Be You National Mental Health initiative are here to support you and your school communities.

Hannah Jamieson National Education Advisor Headspace Schools (Be You) hjamieson@headspace.org.au

Will the Quality Time Action Plan reduce teacher workload?

5 min read

Teachers want more time for lesson planning, not less.

Last week, the NSW Department of Education released the Quality Time Action Plan, intended to “simplify administrative practices in schools”. Having highlighted the concerning growth in administrative workload in schools in a report based on a survey of more than 18,000 teachers for the NSW Teachers Federation in 2018, we were excited to hear about this development.

A way forward for reducing administrative workload?

The Plan provides a commitment to “freeing up time”, through a targeted “reduction of 40 hours of low-value administrative tasks per teacher per year”. Administrative work was the overriding concern for teachers in our workload survey, with more than 97% of teachers reporting an increase in administrative requirements in the five prior years. Further research shows that the heavy workload of teachers pre-pandemic was intensified by COVID19 in 2020. As researchers in the field and advocates for the important work of teachers, we find it encouraging to see tangible efforts made to address teacher workload.

According to the Plan, issues with administration are to be addressed through six “opportunity areas”: 1) curriculum resources and support, 2) assessment and reporting to parents and carers, 3) accreditation, 4) processes and support services, 5) extracurricular activities, and 6) data collection and analysis. Some of these areas, especially data collection and analysis, resonate with what we heard from teachers in our 2018 survey. And importantly, some of the actions in the Action Plan do seem to provide tangible reductions in the time teachers spend on this kind of work, such as automating data processing that was previously manual.

Avoiding the narrowing of teachers’ work

But other target areas of the Plan were more surprising to us, particularly those around curriculum. The Plan acknowledges that “skilled programming and lesson planning are a critical part of teaching” – but also states that “this task can be quite time consuming”. It offers to improve “the accessibility and quality of teacher resources” to “save hours of time teachers previously used creating and searching for content”. We’re not the only ones who were surprised by this inclusion – we noted plenty of social media discussion from teachers about it last Friday after the plan was released to them.

We don’t have access to all of the data upon which the Department is basing its Plan. Maybe there are teachers who have called for more assistance in programming and lesson planning. There is, to our knowledge, no published research suggesting that this is a problematic workload area for teachers, although it has been a noted challenge in relation to conversion to remote teaching during the pandemic. This Plan strategy does seem to be at odds with the findings of our survey that teachers’ most valued activity, the one that they saw as most important and necessary, was “planning and preparation of lessons”. Similarly, teachers reported wanting more time for “developing new units of work and/or teaching programs”. They did not want to do less of this kind of work, in contrast to what the Plan seems to propose.

According to policy analyst and scholar Carol Bacchi, policy documents always serve to create or give shape to policy problems. That is, for Bacchi, any ‘solution’ given in a policy is actively constructing a particular kind of ‘problem’ to be addressed. So it’s interesting that the Plan constructs class preparation as part of the teacher workload ‘problem’. This suggests that the problem isn’t that teachers need more time to do their preparation, but that the way in which they have been preparing in the past has been inefficient, with the solution to instil a more centralised approach. While teachers may be appreciative of such resources, it’s not what they advocated in our survey, where the top recommended strategy was to reduce face-to-face teaching time to facilitate a closer focus on collaboration for planning, programming, assessing and reporting. Similarly, we note that the NSW Teachers Federation salaries and conditions campaign launched last week, ‘More Than Thanks’, is – along with higher salaries – calling for an increase in preparation time of two hours a week, to enable this kind of work.

There are also other interesting framings of the teacher workload problem in the Plan. For example, the support around data collection and analysis seems to be mostly about ‘streamlining’ existing requirements rather than removing them. This tells us that the perceived problem is not the data itself but how it is collected and reported.

Lesson planning is core to teachers’ work

Given that the Action Plan’s intended focus is on ‘administration’, this makes us wonder what ‘administration’ in teaching is understood to include. What is considered ‘administration’ and therefore peripheral, and what is considered ‘teaching’ and therefore core? This is quite a high-stakes question. Because if we position some aspects of teachers’ work as simply ‘administration’, then we run the risk of sidelining work that teachers value as part of their professional identity, such as the creative and intellectual work of lesson planning.

We are wary of any policy approach which re-purposes concerns over workload as an opportunity to control or limit the central pedagogical labour of teachers. Reforms which chip away at the core work of teachers, where both societal contribution and teacher satisfaction is most concentrated, run the risk of damaging the profession and the education system it carries.

This may not be what happens under the Quality Time Action Plan. But given recent concerns over the commercialisation of education data and resourcing, it is worth asking whether it would be the profession itself providing centralised programming and planning resources, or if this would be outsourced.

Teachers’ voices matter: give your feedback

There is an opportunity to provide feedback on the Action Plan. We encourage teachers – those who live these matters each and every day – to fill in the feedback form. Workload issues are as complex as they are important, and we heartily welcome the ongoing efforts of all stakeholders to effectively support the people who staff our schools.

Rachel Wilson is Associate Professor at The Sydney School of Education and Social Work at the University of Sydney. She has expertise in educational assessment, research methods and programme evaluation, with broad interests across educational evidence, policy and practice. She is interested in system-level reform and has been involved in designing, implementing and researching many university and school education reforms. Rachel is on Twitter @RachelWilson100

Susan McGrath-Champ is Professor in the Work and Organisational Studies Discipline at the University of Sydney Business School, Australia. Her research includes the geographical aspects of the world of work, employment relations and international human resource management. Recent studies include those of school teachers’ work and working conditions.

Meghan Stacey is a former high school English and drama teacher and current lecturer in the School of Education at UNSW Sydney. Meghan’s primary research interests sit at the intersection of sociological theory, policy sociology and the experiences of those subject to systems of education. Meghan’s PhD was conferred in April 2018. Meghan is on Twitter @meghanrstacey

Mihajla Gavin is a lecturer in the Business School at the University of Technology Sydney, and has worked as a senior officer in the public sector in Australia across various workplace relations advisory, policy and project roles. Mihajla’s research is concerned with analysing the response of teacher unions to neoliberal education reform that has affected teachers’ conditions of work. Mihajla is on Twitter @Mihajla_Gavin

Scott Fitzgerald is an associate professor and discipline lead of the People, Culture and Organisations discipline group in the School of Management at Curtin University. Scott’s research presently covers two main areas: the changing nature of governance, professionalism and work in the education sector.

This article was originally published on EduResearch Matters. Read the original article.

Caritas Australia School Update

Caritas Australia School Resources - www.caritas.org.au/resources/school-resources/

Catholic Earthcare Schools Program - https://catholicearthcare.org.au/earthcare-certified-schools-program/

Poverty-themed resources - www.caritas.org.au/resources/school-resources/?Keyword=poverty

Fratelli Tutti animation video - https://vimeo.com/566397180

Social Justice Calendar for 2022 - www.caritas.org.au/resources/school-resources/?Keyword=Social+Justice+Calendar+2022

Ecological Justice Calendar for 2022 - www.caritas.org.au/resources/school-resources/ecological-justice-calendar-2022-by-catholic-earthcare-australia/

Advent Resources (Coming soon) - www.caritas.org.au/advent

Join the Justice Education Facebook Page - www.facebook.com/groups/3125271991128797

Why we must talk about teacher professionalism now

In 2016, Judyth Sachs reflected on her 2003 monograph ‘The Activist Teaching Profession’ and asked, ‘Teacher professionalism: Why are we still talking about it?'. In that paper, she argued ‘the time for an industrial approach to the teaching profession has passed’ and made a case for ‘systems, schools and teachers to be more research active with teachers’ practices validated and supported through research’ (p.413). I am not sure what Judyth would say five years later but I think this is the discussion that still needs to be had. We do need to talk about teacher professionalism in Australia in 2021 and particularly the way it is being constructed and reconstructed through teacher education policy.

In 2020, Martin Mills and I compared teacher professionalism as it was constructed in teacher education policies in Australia and England, and concluded,

… derision and mistrust of teacher education is evident in both contexts. The construction of teacher professionalism through the policies in Australia and England reflects a managerial approach dominated by performance cultures, increased accountability, and teacher standards … the extent to which teachers research and improve their practices, and invoke professional judgement involving interrogation of available research … rarely feature .

Mayer & Mills, 2020, p.14

The 2014 Teacher Education Ministerial Advisory Group (TEMAG) review and the resulting updated accreditation standards and procedures have constructed teacher and teacher educator professionalism in Australia. Two key drivers are evident: making sure the ‘right’ people come into the profession and making sure beginning teachers are ‘classroom ready’. Teacher education was clearly positioned as a problem that could be fixed by tighter accountability mechanisms related to these drivers.

While the TEMAG review claimed to consider ‘wide-ranging evidence and research’ in recommending that the Australian Government act ‘on the sense of urgency to immediately commence implementing actions to lift the quality of initial teacher education’ (Recommendation 2), previous government reports, governments commissioned research consultancies, and/or reports from multinational entities like the OECD and McKinsey & Company, were used to support a perceived need for change. Peer reviewed and published research by teacher education academics rarely featured. In this way, evidence to support the claims and recommendations was constructed in a particular way, supporting Helgetun and Menter’s (2020) claim that evidence is often a rationalized myth in teacher education policy because policies are regularly politically constructed and ideologically based.

An important component of the TEMAG argument and recommendations, as captured in the report’s title, was that graduates from teacher education programs must be ‘classroom ready’. As a result, teacher education accreditation requirements changed to include a final-year teaching performance assessment. This caused much upheaval, requiring significant changes to the teacher education curricula and to teacher education resourcing in order that programs remained accredited. However, little attention was given to what should be assessed; that is, what beginning teachers should know and be able to do. More attention was given to how teacher educators must design and implement the performance assessment, and various accountability mechanisms for surveillance of this process. The assumption seemed to be that the already developed Australian Professional Standards for Teachers accurately detailed the required professional knowledge, practice, and engagement, and that what was needed was a tighter accountability framework for teacher educators and their practices. Of course, regular critiques of such standards highlight how they construct a particular type of professionalism by focussing on what teachers do rather than what and how they think. None of this was not interrogated in the TEMAG review.

In addition, great emphasis was given to ensuring that the ‘right’ people come into the profession. This focus on the person (i.e., on teachers, not their teaching) resulted in recommendations about required academic skills and desirable personal attributes and characteristics for entry to teacher education programs. In the end, measures of academic skills ended up being the Australian Tertiary Admission Rank (ATAR) and levels of personal literacy and numeracy. Of course, many teacher education entrants are not secondary school graduates. Thus, the political and media hype about ATAR and the quality of the teaching profession is misguided. In relation to personal levels of literacy and numeracy, TEMAG recommended that teacher educators ‘demonstrate that all preservice teachers are within the top 30 per cent of the population in personal literacy and numeracy.’ Not surprisingly, this 30% category proved rather challenging to associate with a score on the Literacy and Numeracy Test for Initial Teacher Education Students.

Another aspect aimed at ensuring that the ‘right’ people were admitted to teacher education was the recommendation for selection processes to assess the ‘personal characteristics to become a successful teacher’ (Recommendation 10).

At its worst, this conjures up visions of the 1930s so-called teacher characteristics ‘research’ associated with what makes a good teacher (which inevitably included being female and liking children).

Ensuring the ‘right’ people come into teaching was translated into accreditation requirements for providers to use non-academic selection criteria and, in practice, this has meant everything from a short personal statement attached to applications to the use of commercially produced tests designed to assess personal characteristics. Moreover, teacher education providers were required to ‘publish all information necessary to ensure transparent and justifiable selection processes for entry into initial teacher education programs’ suggesting a mistrust in providers to make appropriate decisions about selection of entrants to their teacher education programs.

Thus, teacher professionalism in Australia is being constructed as being the right type of person with appropriate personal characteristics and levels of personal literacy and numeracy, who can demonstrate successful teaching practice against standards within a system that determines performance indicators and mechanisms for classroom readiness. Moreover, teacher educator professionalism can be interpreted as ensuring the production of graduates who are classroom ready at point of graduation via programs that are accredited using nationally consistent standards.

In Australia and in England, the relentless reviewing of teacher education continues in 2021. And, yet again, the wording does not disguise the goals of these reviews. In Australia, the ‘Quality Initial Teacher Education Review’ will consider how to attract and select high-quality candidates into the teaching profession and how to prepare ITE students to be effective teachers Nothing new to see here. In the UK, the Initial Teacher Training (ITT) Market Review is focussing on ‘how the ITT sector can provide consistently high-quality training, in line with the core content framework, in a more efficient and effective market’

Do we need to keep talking about teacher and teacher educator professionalism? Definitely!

Diane Mayer is a professor of education (Teacher Education) at the University of Oxford and an honorary professor at both the University of Queensland and the University of Sydney.

This article was originally published on EduResearch Matters. Read the original article.

Playground duty really is quality time: how joyful learning happens outside the classroom

The Quality Time Action Plan is described by the department of education as an approach intended to reduce and simplify administrative processes for teachers and provide them with more time for “high value tasks”. It is here that I have a quibble with this document and its definition of playground duty or supervision at lunch and recess as a “non-teaching activity”. I see this definition as problematic and at odds with the important role teachers play on school playgrounds and the learning that takes place in this setting.

Teaching does not just happen in the classroom

The playground is one of the most important places of learning, it is here that children and young people develop socially, physically and practice a degree of autonomy outside of the classroom. A learning that is as important as that which takes place indoors. The role of the teacher is far more than a provider of knowledge. Relationships are the heart of our work. The playground offers us a space to interact with our students, to observe them in a different light, learn about their interests, strengths and vulnerabilities- an understanding that is essential for building our professional knowledge and informing practice.

Teachers on the playground have a role that goes beyond keeping children physically safe and opening yoghurt. It is here they can offer support to students as they negotiate new or challenging social and physical situations. The playground offers young people a place for autonomy and socialisation. It is here they practice important skills that contribute to their social competence, such as sharing, managing conflict, making friends and learning new skills. Teachers participate in this learning by ensuring students have appropriate equipment to play, such as balls, hoops and skipping ropes. They can make suggestions about how to communicate more effectively, self-regulate, take risks or de-escalate conflicts.

In American schools, playground duty is provided by non-teaching staff, often a parent is paid to fulfil this role. In my experience this resulted in confusion as school rules were implemented inconsistently and according to the assumptions of the adult standing on the yard. I recall one officious parent banning children from trading pokemon cards for no apparent reason other than she did not like the game. Students had no idea when they could run, what they could play or often why they were in trouble. What happened on the playground often stayed on the playground and teachers remained unaware of the social dynamics and the impact they had on the children in the classroom.

Playing is learning

The wording in the action plan denies the important role of teachers in supporting this learning. The playground is a valuable resource for students and teachers as it is the primary place for playing. Play, in its many variations in primary and secondary years, offers much more than a place for children to “let off steam”. Vital social and emotional learning happens when children play and interact on the playground, they develop their awareness of themselves, of others and their capacity for acting with responsibility and kindness. Teachers can model this for children, to facilitate play in the early years, and in the primary and secondary years, encourage social inclusion and give emotional support when needed; this can be as simple as putting on a band-aid to address complex matters such as bullying. The playground is the heart of the school community and a place for students and teachers to play and come together for the wellbeing of all.

Our duty when schools reopen

Studies show that student wellbeing should be the highest priority for schools when they re-open. For many students, learning from home has been a period marked by significant anxiety and social isolation. Reports show what our students missed most about school was playing with their friends and their teachers. Removing teachers from the playground takes away their opportunity to reconnect with their students, to be present with them as they return to school, to share their concerns and more importantly experience the joy of being together again. Surely this should be considered as “a high valued task”.

Olivia Karaolis teaches across the School of Education and Social Work at Sydney University. She completed her research at USYD after working in the United States in the field of Early Childhood Education and Special Education. Her focus has been on creating inclusive communities through the framework of the creative arts.

Main image: CC BY-SA 2.5, https://en.wikipedia.org/w/index.php?curid=6427507

This article was originally published on EduResearch Matters. Read the original article.

10 min read

Brendon Hyndman, Charles Sturt University

A newly published study in the journal PLoS ONE suggests spending time on screens is unlikely to be directly harmful to young children. The US study attracted global attention, as screen time has been commonly blamed for disrupting the healthy habits of our youth.

Headlines announced “Screens are not as dangerous as you think”, “Screens don’t really hurt kids”, “Kids are not harmed by long screen times”, “Potential benefits of digital screen time” and “Kids being glued to screens doesn’t cause anxiety”.

However, we still need to be wary of health consequences, despite the absence of strong links between screen time and children’s health. The researchers suggested screen time was not a direct cause of depression or anxiety and was linked to improved peer relations, but their findings came with caveats. The study involved almost 12,000 nine-to-ten-year-olds from 24 diverse sites across the United States.

Read more: Kids and their computers: Several hours a day of screen time is OK, study suggests

Why worry about screen time?

Young people are using screens more than ever. The average number of screen-based digital devices reported to be owned and used by children in Australia has reached 3.3 devices per child.

These devices include laptops, smart phones, televisions, tablets, gaming devices and family computers. Similar to many Western nations, children are estimated to be using a mobile device or watching television for 3-4 hours a day and exceeding health guidelines.

Surveys have found almost all high school students and two-thirds of primary school students own a screen-based device. Children are spending at least a third of their day staring at screens.

In Australia, teachers and parents have expressed concerns that the fast uptake of digital devices (including social media use) is having negative impacts on children’s physical activity and their ability to be empathetic and focus on learning tasks.

Read more: Children own around 3 digital devices on average, and few can spend a day without them

Most concerns relate to screen time being associated with depression, anxiety, self-esteem, social interactions and sleep quality.

With children using screens so much at an early age, establishing a causal link between screen time and health outcomes has become more important than ever. Increased screen use as a result of the pandemic has added urgency to this research.

What did this latest study investigate?

The US study investigated the relationship between screen time and children’s academic performance, sleep habits, peer relationships and mental health.

Parents completed a screen time questionnaire, a child behaviour checklist and anxiety statement scales (including sections on children internalising or externalising problems and attention). They reported on their child’s grades at school, their sleep quantity and quality, family income and race.

The children independently completed a 14-item screen time questionnaire about the different types of recreational media use on screens. They were also asked how many close friends they have.

The researchers did find small significant associations between children’s screen time and decreases in quality of sleep, attention, mental health and academic performance. These effects were not confirmed as directly caused by screen time.

Possible explanations for the weak links between screen time and negative health impacts include:

- relying on parent reporting

- the design of the screen time survey

- social quality measurement.

Parent reporting has limitations

Most of the assessment relied on parents being able to report accurately on their children’s health behaviours. Surveys and questionnaires are often more reliably completed by the target participants, unless they are unable to do so (for example, due to illness).

It can be difficult for adults to properly identify children’s behaviours, and parents reporting on a child can lead to many inaccuracies or less sensitive data associations. For instance, it would be very difficult to report on a child’s sleep disruptions without using a digital measuring device.

Parents are also relying on how much they see their child, the depth and openness of their conversations, various family structures, shared interests and conversations with teachers.

Survey design matters too

It’s important that surveys are easily understood and suitable for the participants. At the ages of nine and ten, kids could still be grappling with the meaning of the different screen time aspects of the survey. They also might not yet fully understand their own behaviours or habits.

In the screen-time questionnaire, the maximum time category was four hours a day and above. This will not identify excessive use. An international study of almost 600,000 children found beyond four hours (for boys) and two hours (for girls) was harmful.

Future research also needs to consider important positive screen strategies such as eye protection, posture, role modelling and active screen games with physical health benefits.

Other major considerations include the different ways children engage with devices. For example, screen time can involve interactional, recreational or passive entertainment. Different devices also require different levels of screen intensity.

The different screen time intensities have varying levels of influence on children’s mental health, life satisfaction and interactions. Researchers strongly emphasise measuring the quality of screen time, rather than the quantity.

Read more: Children live online more than ever – we need better definitions of ‘good’ and ‘bad’ screen time

How do you define close friends?

The social survey focused on how many close friends a child has. This will not always mean social quality. A child may think of all contacts on social media as close friends and may simply be interacting with more people when using their devices.

Because the study relied on a quantity criterion with the wording “close friends”, we can’t be sure screen time actually strengthened peer relations.

In addition, it is an early age to be measuring screen use as research shows non-sedentary behaviours (that is, physical activity) peak later in primary school. This is when children are most active, engage in less screen time and most enjoy outdoor play compared to later years of schooling.

Where to from here?

The study has laid a foundation to add further comparisons and evidence as the participants approach adulthood in the next decade. It reinforced the influence of socio-economic status (SES) on children’s health and identified key trends, with boys reporting more total screen time during weekdays and weekends than girls.

Parents and teachers still need to show caution with children’s screen time, as the study did find associations between screen time and a variety of negative impacts on kids’ health.

Even if the negative outcomes were not identified as major and screen time wasn’t established as the direct cause, a review of research suggests we are unable to rule out these associations.![]()

Brendon Hyndman, Associate Dean (Research), Charles Sturt University

This article is republished from The Conversation under a Creative Commons license. Read the original article.

Read LessA prayer, a plea, a bird

A prayer, a plea, a bird

Julie Perrin

The title of Julie Perrin’s new book catches perfectly its style and its content. The words are as few as needed, and each of them is evocative. It contains many fine and chiselled prayers for all seasons and predicaments. They touch the heart and sit easily on the tongue and ear. The words are modest and direct. I was particularly taken by this prayer during Coronavirus that names unflinchingly the experience and yet moves into an image that can awaken hope.

God of Shadows.

Give shelter to hollow, shaken humans

bewildered by sudden closure.

Sturdy structures shattered, hopeful trade ended,

meaningful work gone.

In the shocking silence when nothing can be said

let birdsong be heard.

Each prayer is a plea, of course, but the whole book itself pleads to the reader to attend to the depths of experience and to the richness of the simplest of human meetings and of the world around us. It draws out the relationships between oneself and other persons and things. And the book is a bird: it takes wing and the reader with it into a world of spirit. Many spiritual books fail in this respect – though wise and perhaps authoritative they remained confined in words that have become stale. They don’t soar and play in the air. Julie Perrin offers new words and images, new stories to tell about ourselves and others.

This little book will be invaluable for personal prayer and for prayer services.

MediaCom Education

ISBN: 9781925722383

Counselling conundrum: How school psychology services have coped with COVID

5 min read

School psychologists and counsellors provide a critical service supporting students with learning and emotional needs. During COVID-19 restrictions, they had to change the way they provided this service.

Given that there have been seven international health crises over the past 20 years, COVID may not be the last one we face.

It’s important we learn from our experiences during COVID, to ensure we continue to support students’ learning and emotional wellbeing during possible future crises, including pandemics.

During COVID-related restrictions in 2020, we conducted a survey-based study across Australia to find out what school psychologists and counsellors did during this time, the innovations they employed, and how they overcame the challenges associated with delivering services during COVID lockdowns.

This is what we found.

1. Online support to students, parents and teachers

Almost all support to students, parents and teachers during this time was provided using video-conferencing or telehealth.

Pivoting to online services gave psychologists and counsellors more opportunities for interdisciplinary collaboration, especially with allied health and other medical professionals.

Various online innovations were used to keep students connected, such as online activity clubs (Lego online, for example). To promote wellbeing, activities supporting mental health were offered, such as online mindfulness for groups of students.

School psychologists presented webinars to parents on child and parent wellbeing, and sent emails to discuss the welfare of both. Teachers were invited to complete wellbeing surveys, and school psychologists and counsellors used online check-ins to support them.

They offered teachers online activities to promote wellbeing and connectedness, such as a virtual wall to post positive stories, and virtual yoga.

Read more: The need for mental health education in Australian schools

Providing online services to students, parents and teachers meant psychologists needed access to the appropriate technology, school IT support, and professional development – the Australian Psychological Society (APS) regularly provides professional development in this area.

How they might engage younger children in online services was a training gap for many. The Parenting Research Centre (PRC) launched a tele-practice website that includes a range of evidence-based information and resources for practitioners working with children and families that may be of relevance.

Pivoting to online services also meant school psychologists needed to quickly identify which online programs had a strong evidence base, and for which student groups (that is, targeting children of different ages and presenting issues). Many school psychologists adapted existing programs for their own needs, and more research is needed to identify intervention components that are essential for positive outcomes.

2. Supporting at-risk students

Various initiatives were employed school-wide to identify and support at-risk students, including asking all students to complete daily wellbeing check-ins.

Other approaches included setting up peer-to-peer support systems, providing regular contact via email, telephone or video conferencing, and connecting students and their families with additional services and support in the community as needed.

Online self-referral forms, and supporting at-risk students to attend school were other strategies employed.

More systematically, psychologists worked with leadership teams, liaised regularly with year-level coordinators, developed clear policies for wellbeing teams to follow, and had clearly defined processes for the identification and management of at-risk students.

3. Psychometric assessments

Perhaps unsurprisingly, school psychologists indicated that during lockdowns they weren’t able to conduct the usual assessments, such as intelligence tests. These are important for funding purposes, and to organise appropriate learning accommodations.

Read more: Leading schools in lockdown: Compassion, community and communication

Face-to-face psychometric assessments were able to be conducted for a small number of at-risk students. However, where psychometric assessments couldn’t be carried out, psychologists offered students, their families and teachers additional strategies and support until face-to-face learning resumed.

4. Managing ethical issues involved with delivery

The psychologists reported it was important to address the ethical issues of online service delivery, including confidentiality, privacy and security. This concern was addressed through the development of consistent policies, procedures and practices. Many psychologists described the value of guidance provided by the APS and AHPR.

5. School leaders

School leadership was vital in communicating the importance of student, staff and parent wellbeing. Likewise, the encouragement of school leaders for their communities, including staff, to access psychological support.

6. Self-care

Psychologists noted the importance of their own self-care and support networks, acknowledging the impacts of COVID-19 on both personal and professional levels.

Psychology and counselling services that support young people’s mental health and wellbeing are critical to their learning success and long-term happiness. This is especially important during high-stress periods such as lockdowns and when returning to face-to-face learning.

COVID-19 lockdowns gave rise to innovative practices that have the potential to increase student access to services when schools return to face-to-face learning. Whether, and how, these practices continue in the long term remain to be seen.

This article was first published on Monash Lens. Read the original article

Read Less