Filter Content

- From the President

- Australian Catholic Super

- Have your say! Principal Perspective of ITE and ways to collaborate and improve the process into the future

- WOODS Furniture

- A year without NAPLAN has given us a chance to re-evaluate how we gauge school quality

- Camp Australia

- The evidence says teachers need more time and more money. Why is the government ignoring it?

- MSP

- Empathy starts early: 5 Australian picture books that celebrate diversity

- From power battles to education theatre: the history of standardised testing

- ACPPAConnect - Have you had a look?

- Useful Tips from Brennan Law

- Is learning more important than well-being? Teachers told us how COVID highlighted ethical dilemmas at school

- GOOD GRIEF

- The need for mental health education in Australian schools

- Catholic Church Insurance CCI

- Celebrating 200 Years of Catholic Education

- ACARA Updates

- Connecting with others remotely: What have we learned from online learning?

- Young Voices Award - Jesuit Communications

- Toolkit for Schools

- Just a thought!

Welcome to you all as we near the end of our first term of 2021.

I think we can all agree that the start of this year in our school communities has been a welcome relief of ‘near normalcy’, which has meant we can all focus clearly on supporting the teaching and learning in our schools.

This week we held our first Board meeting of the year and I would like to share some of the national insights of the group.

- Our immediate past president, Mark Mowbray was awarded ‘life membership’ of APPA by the Minister for Education and Youth, Hon. Alan Tudge. This is well-deserved recognition of Mark’s many years of service and dedication to Catholic education in schools, Associations and now as a Board member of AITSL.

- At this meeting I was able to meet the Minister briefly and share with him some of our ongoing initiatives. We hope to meet with him further in the coming weeks.

- We held a valuable discussion with Mark Grant, CEO of AITSL, around initial teacher education, teacher registration, the Disability Review, and the progression of the reduction of ‘red tape’ for teachers.

- Recent ACPPA media releases have responded to both the launch of the ACU/Deakin University Principal Health and Wellbeing survey, now in its 10th year and the Ministers speech about “raising the bar’ in education.

- Our latest ACPPA national survey results again provided us with a snapshot of principal engagement with our Association. While we have seen steady trends in good levels of engagement, we now need to look at other ways to motivate Principals to see the benefit of having a voice on national agendas which impact their schools. We hope to put out a summary information page about our results in the coming months for your comment and review.

- As part of our ongoing commitment to Principal Health and Wellbeing, our ACPPAConnect portal has been well received. You can find out more about this initiative further on in TOPICS. We are also exploring some other member services for supporting your wellbeing, which we will share in the coming months.

- Lastly, I urge you to participate actively in our much-anticipated ACPPA research project. This is a key opportunity to have your voice heard about your perspective of Initial Teacher Education and ways to improve it in the future. At no other time in our Association’s history have we been better placed to have an impact on the development of teaching graduates which are the cornerstone of our schools going forward. The details are listed below for your reference.

Regards

Brad Gaynor

ACPPA President

Investing in a near-zero interest rate environment

The official cash rate has remained at an unprecedented low of 0.1% in response to severe economic weakness caused by the COVID-19 pandemic.

Expected returns on long-term bonds have also continued to fall with the 10-year government bond yield, which is the rate of return expected from investing in Australian government bonds, falling to 1% per annum in 2020.

Short-term cash rates and long-term bond yields tend to move in the same direction in response to changes to the economic outlook. The current rates, which are reflected in term deposit and mortgage rates, indicate a weak outlook for the Australian economy.

By decreasing the cash rate, the Reserve Bank of Australia aims to stimulate the economy by encouraging spending and investing via low returns on savings and reduced borrowing costs respectively.

What does this mean for investments in bonds, cash and term deposits?

Given the reduction in the official cash rate and fall in bond yields, there is a risk that future returns from these investments will be low and may even be negative.

In the past, falling interest rates have enabled the bonds to perform well with a return of 4.6% per annum over the past five years[i]. However, with interest rates currently at all-time lows, it’s unlikely that they would fall further. Hence, the returns on bonds that we’ve seen previously are not expected to repeat in the foreseeable future.

Similarly, the returns from cash and term deposits have significantly reduced. The average return for cash over the past 10 years has been 2.4% per annumi, but with current rates at such low levels, it is unlikely that we will see these returns repeat in the next 10 years.

What has Australian Catholic Superannuation done about this?

In response to the downward trend in cash rates and bond yields, Australian Catholic Superannuation has reduced its exposure to bonds, cash and term deposits in favour of investments that offer better prospective returns including corporate bonds, bank debt and increasing the Fund’s exposure to equities[ii].

What can I do about it?

You are encouraged to consider your personal circumstances and ensure that your investment decisions are aligned with your tolerance for risk.

If you are a member of Australian Catholic Superannuation and need help with managing your finances, we offer advice on your superannuation investments, contributions or insurance at no additional cost through our limited advice team. Alternatively, we also offer comprehensive advice that looks at a broader range of topics including your finances outside of superannuation. Find out more about our different types of financial advice services or make an appointment today.

If you’re not a member of the Fund but would like to find out more, visit catholicsuper.com.au or contact our award-winning Member Services team today.

Any advice contained on this webpage is of a general nature only, and does not take into account your personal objectives, financial situation or needs. Prior to acting on any information on this webpage, you need to take into account your own financial circumstances, consider the Product Disclosure Statement for any product you are considering, and seek independent financial advice if you are unsure of what action to take. Past performance is not an indicator of future performance.

[1] Bloomberg AusBond Government Bond Index.

[1] Investment options with a higher percentage of growth assets generally expect higher returns over the long term but have higher risk and are also likely to experience larger fluctuations in returns from year to year and more frequent negative returns.

Read LessThe much anticipated ACPPA research project is coming!

Over recent years ACPPA has been hearing from Principals across Australia about their concerns with both student teacher readiness and the connection with Universities in preparing these students effectively.

As a part of our commitment to all Principals across Australia to have a voice that is heard and acted upon, ACPPA has created a partnership with our two national Catholic universities to do a study around the following relevant topic in 2021.

The ACPPA National ITE project is underway.

It is in collaboration with Australian Catholic University and the University of Notre Dame (with sponsorship from National Catholic Education Commission (NCEC), ACPPA seeks to explore Principal understanding and lived experience of initial teacher education training and program delivery.

The project uses survey tools and face to face focus group interviews (subject to COVID-19 health announcements) to gain insight about the efficacy of ITE and opportunities for enhancing educational performance and Principal engagement.

It seeks data and feedback to improve and refine the process to ensure student teachers are well prepared for working in school communities in a changing and dynamic environment. Areas for exploration include:

- a) The day-to-day performance, activities, skill set and expectations of initial teachers.

- b) The input primary school principals have on employment, training, mentoring, performance review and feedback for initial teachers.

- c) Feedback from current primary school principals about the programs, offerings and value of tertiary education and training for initial teachers.

Project outcomes include:

- Potential to improve cross correlation – school sector with tertiary sector

- Opportunity to inform program improvement

- Increased front line input to ITE

- Opportunity to develop further pilot programs

- Build capacity in both sectors

Encouragement to Participate in both survey and focus groups

Proposed timeline

Indictive Project Timeline

|

March 2021 |

Finalisation of survey questions and focus group questions Ethics Approval sought |

|

20th April 2021 tbc |

Survey opens |

|

18th May 2021 |

Survey closes |

|

June -August 2021 |

Principal Focus groups and interviews take place |

|

August 2021 |

Reports created |

|

October 2021 |

Report launch and promotion |

The best outcome for the ACPPA members and the Universities is participation being extremely high. This is for both the online survey and the focus group sessions. We encourage members to take part in the project and a number of Diocesan Directors have shown interest in the project also.

This is a key and pivotal opportunity for our Association to share a clear and united voice as Australian Catholic Primary Principals on a topic which is fundamental to the advancement of our sector.

If you would like input about the project at a leadership meeting, Association meeting, Diocesan meeting or other event please contact me as soon as possible.

PAUL COLYER - Australian Catholic Primary Principals Association

Phone: +61478973767

Email: paul.colyer@acppa.catholic.edu.au

A year without NAPLAN has given us a chance to re-evaluate how we gauge school quality

5 min read

This has been a year of schools closing and a rapid switch to online learning. It’s also been a year with no NAPLAN. The cancellation of the National Assessment Program – Literacy and Numeracy due to COVID marked the first interruption of the annual testing cycle since 2008.

NAPLAN is a standardised test, conducted yearly for students across the country in years 3, 5, 7 and 9. It has been used by teachers, schools, education authorities, governments and the broader community to see how children are progressing against national standards in literacy and numeracy — and over time.

After the changes COVID brought to education, policymakers have an opportunity to rethink our national “high-stakes” testing system that focuses on literacy and numeracy skills. It often leads teachers to “teach to the test”, rather than ensuring students leave school with a well-rounded set of skills.

NAPLAN scores are used to gauge the quality of schools. But the overemphasis on only literacy and numeracy scores stands in the way of providing a more holistic education. We need a system that delivers confident citizens and creative problem-solvers. And that means re-evaluating what we mean by a good-quality school.

A history of NAPLAN and My School

More than a decade ago, Australian leaders envisioned a national system that assesses school quality. In 2010, led by then education minister Julia Gillard, the Australian Curriculum, Assessment and Reporting Authority (ACARA) launched the My School website.

The move was influenced by countries such as the US and UK, which employ formal and non-formal school rankings to show the quality of schools. My School did this by reporting NAPLAN data, accompanied by up-to-date information such as schools’ missions and finances.

Julia Gillard still stands behind her controversial decision, while acknowledging the system’s serious problems. These include its overemphasis on the test, rather than a focus on the processes of learning and inquiry.

Research shows the “teach to the test” approach can narrow the curriculum focus and make it harder to cater for students’ various needs. It can limit opportunities for students to engage with the materials in ways that develop their learning and critical thinking skills.

Read more: Too many adjectives, not enough ideas: how NAPLAN forces us to teach bad writing

A change to the My School website

While educators lamented the negative impacts of NAPLAN, parents have constantly complained the My School system left them confused, feeling as if they were sitting in a test themselves. The Council of Australian Governments (COAG) commissioned a review of NAPLAN.

The very long review process consisted of public submissions, focus groups and interviews with stakeholders, parents and unions. The resulting report showed a relatively unified confusion around the purpose of NAPLAN and My School.

It also showed concerns about displaying test scores alongside the school’s socioeconomic index. This amplified the fact students in the most disadvantaged areas were substantially more likely to score below the national minimum standard for each of the test’s three domains than those in more advantaged areas.

Read more: Not all parents use NAPLAN testing in the same way – and it may be related to their background

ACARA simplified the website, noting the changes agreed to by education ministers after the review’s report came out.

Before, it compared a school’s NAPLAN result against the average result of 60 similar schools. Now, a school’s results are benchmarked against the average NAPLAN score of all students across the country with a similar background.

The website seeks to provide a greater focus on student progress (using NAPLAN results), rather than on statistical comparisons. So, before entering My School, the user must accept a list of terms, which acknowledge:

"... the content on this site about the performance of a school on any indicator, including the National Assessment Program ─ Literacy and Numeracy (NAPLAN) tests, is only one aspect of the information that should be taken into consideration when looking at a school’s profile."

This statement is followed by another about the importance of speaking to “teachers and principals to get an understanding of what each school offers”. Both of these suggest there has to be more to a national system to provide meaningful information that supports transparency and accountability of Australian schools.

This notion is clearly reflected in other Australian education policies, including in the report from the Review to Achieve Educational Excellence in Australian Schools (also known as Gonski 2.0). The report urges the education system to be more creative in the curriculum, assessment and reporting.

How can the system be improved?

It would be foolish to say there is an easy silver-bullet assessment solution. But it may be worthwhile to consider some international initiatives.

'A year without NAPLAN' was the best thing to come out of this pandemic for education#aussieED

— Marc Warwick (@marc_warwick) 22 November, 2020

All 50 US states have established educational measurement systems based on standardised testing. These have been heavily criticised for hurting schools and students. Criticisms include concerns over widespread cheating issues and schools inflating test scores to create the illusion of improved equity and school quality.

Read more: What makes a school good? It's about more than just test results

US scholars lamented the nation’s “testing charade” and its measuring too little about schools and too much about families and neighbourhoods. They sought to look beyond a single test, suggesting a novel assessment framework that paints a more nuanced picture of schooling.

The framework explores what many would agree are crucial aspects of education. Aside from literacy and numeracy scores, they include:

-

student-teacher relationships

-

physical and emotional safety

-

a sense of belonging

-

student engagement and achievement

-

problem-solving

-

relationships between the family and school

-

cultural responsiveness

-

social and emotional health

-

community involvement.

These are measured through the use of tools such as administrative data, and student and teacher surveys. One such alternative system can be found, among others, in Massachusetts, US.

Research on pilots of such a framework show a less deterministic relationship between school quality and students’ socioeconomic status.

Standardised tests can be useful for educators and policymakers who seek to track some student progress and allocate resources. But these tools are limited in what they tell us, and can be misleading.

Creating a new schooling framework that has a less deterministic relationship between school quality and students’ socioeconomic status will be challenging. But it is possible and worthwhile in the long run.

Ilana Finefter-Rosenbluh does not work for, consult, own shares in or receive funding from any company or organisation that would benefit from this article, and has disclosed no relevant affiliations beyond their academic appointment.

This article originally appeared on The Conversation.

This article was first published on Monash Lens. Read the original article

The evidence says teachers need more time and more money. Why is the government ignoring it?

10 min read

Governments must stop telling teachers to scale up practice by copying strategies developed for another school’s context. The latest change in NSW education policy again confuses teacher learning from their own evidence-based practice with guidance from practice developed elsewhere.

Scaling up won’t work for improved learning outcomes. Here’s why. The context of our schools is significant for developing evidence-based practice. Trotting out: “Here’s what worked in this A ranked school” is as pointless as mandating protocols across subjects or year levels within one school.

And let’s not even get into the contentious lack of clarity on measures of the ‘most successful schools’. UNSW Professor Pasi Sahlberg told us this exactly three years ago. He cautioned teachers to ‘avoid urban legends’ in his 2018 book FinnishED Leadership. After decisive longitudinal research in Australia, the call for no more reform hangs on hope.

But hope just won’t cut it with the latest proposed Successful Schools Model for NSW. The first point the model makes (evidence-based practice) and last point (scaling of practice) are counter-productive, counter-research and counter-teacher-led-inquiry in context.

The hopes educators have for fewer administrative burdens and practical support are illusive. The government says it requires teachers to work from an evidence base yet overall policy selectively draws on the wording of research without a concrete offer of structural change.

Governments must action the well-worn call for time and money for teacher professional learning (TPL) where it happens - in schools.

The complexity and time required for TPL are highlighted in the recent findings and recommendations from the independent Gallop inquiry Valuing the teaching profession commissioned by the NSW Teachers Federation. A case in point - will teachers have time to respond via survey on the recommendations of the report? The imperative for government is clear. TPL requires significant structural change to provide the allocated time and salary increases for the essential collective work efforts of the teaching profession.

The profession and the research literature tell us all we need to know. The Australian experience of TPL within a global perspective is outlined in my book Enacted personal professional learning (EPPL): Re-thinking teacher expertise with story-telling and problematics. The idea of EPPL is that teacher learning is complex, contextual, collectively driven, and takes time.

Now, complexity is not the same as difficulty. More difficult means that the understanding and skills become harder by building from the same basic level, that is, the examples become harder. More complex means that the understanding and skills require multiple relations or interactions within context.

So for teachers, complexity occurs among individual learners in one class, between classes when teaching the same subject, or across different learner developmental levels. This complexity occurs throughout the teaching and learning process, which is why pedagogical models continue to be grappled with by both teachers and researchers.

Teachers develop expertise together in dealing with complexity of practice throughout their career. However, teacher collective efficacy (CE) doesn’t come from being a ‘diva’. A diva school or teacher is inwardly focused on their own development and outwardly focused on achievement in competing with others. This undermines empowered teacher learning through a collective practice-based inquiry that meets all individual needs. Enacted personal professional learning (EPPL) requires approaches that develop professional trust in context with colleagues and enable collectively successful practice to flourish. Communities of teachers working in situ on longitudinal TPL programmes draw on teacher’s individuality to harness the collective learning. This work is both difficult and contextually complex - and ongoing. Articulating the thinking of teachers and their students is a continuing challenge in developing a shared language of learning. One of the positives teachers were able to take from the COVID-19 crisis is that it highlighted the difficulty and complexity of teacher work and learning to those uninitiated to the profession.

Challenges and achievements of teacher professional learning

One teacher professional learning (TPL) programme that was conducted across nine different school contexts enabled teachers to develop strategies through evidence-based practice. Cultivating a schoolwide pedagogy: Achievements and challenges of shifting teacher learning on thinking details the findings and recommendations. Various combinations of teaching teams from either a learning stage, curriculum area, or cross-curricular areas considered their own practice for cultivating a schoolwide pedagogy. The longitudinal time frame allowed teachers to trial a variety of strategies drawn from the formal and informal research literature. Teachers used a shared pedagogical model to understand the scope of learning thinking through an inquiry-based approach. Evident in the creation of pedagogical protocols was the need for teachers working together in context. The impact on learning outcomes was evidenced in the shared thinking on and language of learning for students and teachers.

The teaching profession needs allocated learning time and commensurate salary increases

Governments must make the overdue structural change for the teaching profession. Workloads need to allocate time for TPL and salaries of teachers need to be increased to recognise the increasingly difficult and complex work of the profession. This action is supported by the research and best-practice of TPL.

Teaching as the learning profession models the use of research to develop evidence-based strategies through inquiry into practice. In some jurisdictions internationally, TPL is included in the employment hours resulting in reduced face-to-face teaching hours and the use of agreed standards to progress individual development plans. In jurisdictions like NSW Australia, TPL is completed in addition to teaching loads with a government mandated approach to PD requirements. This does not allow for the potential achievements of changed practice through the collective work efforts of teachers.

The end of the 2020 school year for teachers was difficult whilst still coping with the constant changes to COVID-19 protocols. In NSW, instead of a steady start to the 2021 school year, teachers were faced with understanding new teacher professional development (PD) maintenance requirements. Teachers now have limited choices with the drastically reduced accredited courses through the decimating de-registration of providers. The NSW government’s action has resulted in the economic damage experienced by many de-registered providers. TPL once offered by these providers is no longer available to meet the diverse needs of teachers and the required re-engineered approach for a blended online and face-to-face environment. Significantly, the bureaucratic approach to PD belies the complexity and time required for long term sustainable TPL that impacts teaching practice and results in improved learning outcomes for students.

What can the time and money do for teacher learning in context?

Below are three identified areas of teacher influence on their own practice and that of colleagues for improved outcomes.

1. Individual and team thinking built through teacher collective efficacy (CE)

Developing new efforts with collective thinking to influence schoolwide improvement is challenging. The constraints on teacher’s time have developed practices of cooperatively dividing the work effort. Teacher collective efficacy (CE) is often misrepresented as collaborative task generation or cooperative marking or reviewing of student work. CE entails the work of teaching teams to garner collective contributions for:

- developing understanding of observations on learning,

- critiquing task requirements,

- assessing student work samples,

- creating reasoned strategies to implement and evaluation in context,

- expanding and clarifying individual teacher thinking with colleagues, and

- collectively developing practice in context.

2. A pedagogical model to support evidence-based inquiry and performance predictions

TPL that offers a pedagogical model enables teachers to predict performance and map progress of learning thinking. Trialling new strategies in classrooms requires allocated time and structural support to overcome various challenges. This is evident for teachers who struggle to change entrenched routines, as well as teachers currently working out of their curriculum learning area or with a new stage level, or those early career teachers still resolving the theory-practice divide.

3. Teacher and student language and thinking on learning

TPL situated in context gives meaning to teacher’s practice and enables shared findings to address what mattered to teachers. Over a longitudinal implementation time frame, teachers are able to track changes in the collective thinking on the influences of student learning and identify changes in practice school-wide. Developing student reasoning and a language of learning in context requires dedicated time for TPL.

The essential call to action for governments is clear. Reward teachers for their collective efforts in learning and teaching through salary increases and allocated time in workloads.

Carmel Patterson, PhD, is Director of Professional Learning and Pedagogy at Stella Maris College Manly and an Industry Fellow in the Faculty of Arts and Social Sciences at the University of Technology Sydney. She has published in her research areas of teacher professional learning and qualitative methodology. Carmel consults on professional learning courses provided by schools, universities, and private enterprise and has a wide array of professional networks.

This article was originally published on EduResearch Matters. Read the original article.

Empathy starts early: 5 Australian picture books that celebrate diversity

5 min read

Ping Tian, University of Sydney and Helen Caple, UNSW

Early exposure to diverse story characters, including in ethnicity, gender and ability, helps young people develop a strong sense of identity and belonging. It is also crucial in cultivating compassion towards others.

Children from minority backgrounds rarely see themselves reflected in the books they’re exposed to. Research over the past two decades shows the world presented in children’s books is overwhelmingly white, male and middle class.

A 2020 study in four Western Australian childcare centres showed only 18% of books available included non-white characters. Animal characters made up around half the books available and largely led “human” lives, adhering to the values of middle-class Caucasians.

In our recent research of award-winning and shortlisted picture books, we looked at diversity in representations of Indigenous Australians, linguistically and culturally diverse characters, characters from regional or rural Australia, gender, sex and sexually diverse characters, and characters with a disability.

From these, we have compiled a list of recommended picture books that depict each of these five aspects of diversity.

Read more: In 20 years of award-winning picture books, non-white people made up just 12% of main characters

Aboriginal Torres Strait Islander characters

Tom Tom, by Rosemary Sullivan and Dee Huxley (2010), depicts the daily life of a young Aboriginal boy Tom (Tommy) in a fictional Aboriginal community — Lemonade Springs. The community’s landscape, in many ways, resembles the Top End of Australia.

Tom’s 22 cousins and other relatives call him Tom Tom. His day starts with a swim with cousins in the waters of Lemonade Springs, which is covered with budding and blossoming water lilies. The children swing on paperbark branches and splash into the water. Tom Tom walks to Granny Annie’s for lunch and spends the night at Granny May’s. At preschool, he enjoys painting.

Through this picture book, non-Indigenous readers will have a glimpse of the intimate relationship between people and nature and how, in Lemonade Springs, a whole village comes together to raise a child.

Characters from other cultures

That’s not a daffodil! by Elizabeth Honey (2012) is a story about a young boy’s (Tom) relationship with his neighbour, Mr Yilmaz, who comes from Turkey. Together, Tom and Mr Yilmaz plant, nurture and watch a seed grow into a beautiful daffodil.

The author uses the last page of the book to explain that, in Turkish, Mr Yilmaz’s name does not have a dotted “i”, as in the English alphabet, and his name should be pronounced “Yuhlmuz”.

While non-white characters, Mr Yilmaz and his grandchildren, only play supporting roles in the story, the book nevertheless captures the reality of our everyday encounters with neighbours from diverse ethnic backgrounds.

Read more: 5 reasons I always get children picture books for Christmas

Characters from rural Australia

All I Want for Christmas is Rain, by Cori Brooke and Megan Forward (2017), depicts scenery and characters from regional or rural Australia. The story centres on the little girl Jane’s experience of severe drought on the farm.

The story can encourage students’ discussion of sustainability.

In terms of diversity, it is equally important to meet children living in remote and regional areas as it is to see children’s lives in the city.

Gender non-conforming characters

Granny Grommet and Me, by Dianne Wolfer and Karen Blair (2014), is full of beautiful illustrations of the Australian beach and surfing grannies.

Told from the first-person point of view, it documents the narrator’s experiences of going snorkelling, surfing and rockpool swimming with granny and her grommet (amateur surfer) friends.

In an age of parents’ increasing concern about gender stereotyping (blue for boy, pink for girl) of story characters in popular culture, Granny Grommet and Me’s representation of its main character “Me” is uniquely free from such bias.

The main character wears a black wetsuit and a white sunhat and is not named in the book (a potential means of assigning gender).

This gender-neutral representation of the character does not reduce the pleasure of reading this book. And it shows we can minimise attributes that symbolise stereotypes such as clothing, other accessories and naming.

Read more: Teen summer reads: 5 books to help young people understand racism

Characters living with a disability

Boy, by Phil Cummings and Shane Devries (2018), is a story about a boy who is Deaf.

He uses sign language to communicate but people who live in the same village rarely understand him. That is, until he steps into the middle of a war between the king and the dragon that frightens the villagers.

He resolves the conflict using his unique communication style and the villagers resolve to learnto communicate better with him by learning his language.![]()

Ping Tian, Honorary Associate, Department of Linguistics, University of Sydney and Helen Caple, Associate Professor in Communications and Journalism, UNSW

This article is republished from The Conversation under a Creative Commons license. Read the original article.

Read LessFrom power battles to education theatre: the history of standardised testing

Ilana Finefter-Rosenbluh, Monash University

Results from the Trends in International Mathematics and Science Study (TIMSS) 2019 testing round were released last week. They showed Australia had improved in Year 8 maths and science, and Year 4 science, from the previous testing cycles.

The TIMSS is a standardised, international assessment administered to check how effective countries are in teaching maths and science. Another international standardised test is the OECD’s Program for International Student Assessment (PISA). PISA examines how well students in secondary schools across 36 OECD countries, and 43 other countries or economies, can apply reading, maths, science and other skills to real-life situations.

Read more: Australia lifts to be among top ten countries in maths and science

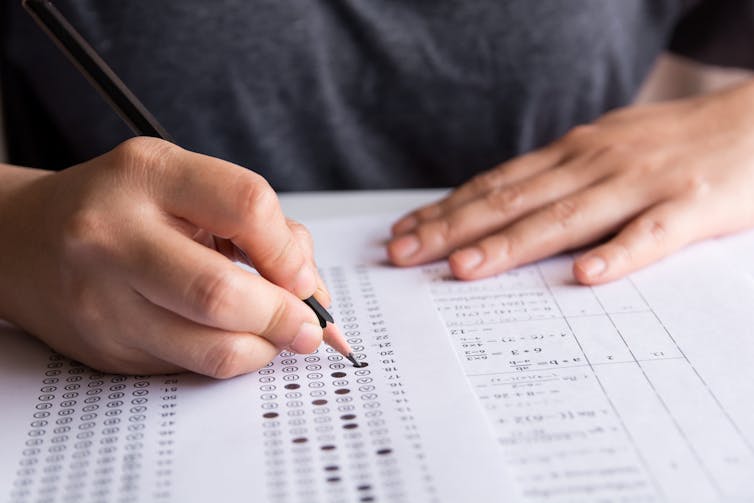

Standardised tests have been in place in a number of educational systems for nearly two centuries. They are rooted in reformers’ desire to regulate schooling and hold educators accountable, in the hopes of improving teaching and learning. But how did such exams gain momentum and why are they so controversial?

What are standardised tests?

Standardised tests are exams administered and scored in a standard, or consistent, manner. They are scored using particular scales of standards in knowledge and skills.

Such tests can be given to large groups of students in the same area, state or nation, using the same grading system to enable a reliable comparison of student outcomes. The tests can be composed of various types of questions, including multiple-choice and essay queries.

In Australia, for instance, 740 schools and just over 14,200 students participated in PISA 2018. The results were compared to those of students in other countries, but also between students inside Australia.

Another well known exam is Australia’s national standardised test, the National Assessment Program-Literacy and Numeracy (NAPLAN), intended for all Year 3, 5, 7 and 9 students across the country.

Similar testing programs to the NAPLAN can be found in other nations, including the UK, Israel, Germany, Mexico and Canada.

So how did it all begin and what makes countries take this approach?

A history of one-size-fits-all student testing

The 17th and 18th centuries saw English and American ministers preaching annual sermons to raise money to educate the poor. This appealed to the generosity of elites, while promoting policies that enforce tax support for charity schools.

The public expected to literally see the fruits of mass education during the industrial revolution; creating a reality in which fundraising and the display of students went hand-in-hand.

As William Reese describes in his prominent book Testing Wars in the Public Schools, “exhibitions” or “examinations” of learning became part and parcel of the US educational system. Such displays were used as a tool for citizens to judge teacher effectiveness and student accomplishment.

Read more: PISA doesn't define education quality, and knee-jerk policy proposals won't fix whatever is broken

Once the days of exhibition were announced, educators’, students’ and even parents’ preparations began. It highlighted their eagerness to impress the public with the childrens’ knowledge.

Often reported by the press to lift community pride and morale, such exhibitions brought a milieu of people, including politicians and members of the school committee, who distributed prizes for meritorious achievement.

Students were focused on the task-at-hand, memorising topics and orally reciting ideas to impress the crowd. Impressions did not only rest on their public performance, but teachers’ ability to successfully discipline them “on stage”.

The rise of standardised testing in the US

By the early 1840s, US reformers Horace Mann and Samuel Gridley Howe, among other reformers, became frustrated by the “theatricality” of education and aggravated by the cruelty of corporal punishment and school exclusivity.

Mann and Howe had witnessed English reformers practising advanced statistics and debating the merits of competitive testing, which soon led to civil service reform and the appointment of inspectors to examine schools.

The two reformers grappled with fundamental questions such as “What makes one school better than others?” and “How can one identify changes in teacher practice and student learning over time?”.

They decided it was time to establish a more formal, consistent and critical testing program than a simple exhibition. They were in favour of written (rather than oral) exams in schools.

Materialising in various Boston grammar schools in 1845, the reformers surprised students with a one hour test attached to a blank answer sheet. A reality of competitive, written, standardised exams that offer quantifiable configurations of teaching and learning had emerged.

Holding sensitive school data in their hands helped the reformers to control issues of teaching, teacher promotion and leave, as well as acceptance and graduation in secondary schools (and later on higher education settings).

A new power battle became the centre of a long-lasting debate about the politics and the meaning of assessment.

What about Australia?

Standardised tests are not new to Australia. Research shows that since the 1800s, and although not consistently, some Australian students have taken part in some form of standardised tests to determine their knowledge, regardless of age.

Large numbers of students, for example, participated in half-yearly exams in the 1820s, administered by Principal Lawrence Halloran at his Sydney school. Similar to the US, external inspectors were also involved for some time in monitoring student achievement on various sets of tasks in schools.

But the standardised testing similar to what we’ve seen in the US was introduced to Australia in 2008 by way of the NAPLAN. This was accompanied by the MySchool website, which lists results for Australia’s students.

Then Federal Education Minister Julia Gillard introduced NAPLAN to give accountability and transparency to families and policymakers on student performance.

The message was very much familiar: let the crowd judge while we, the reformers, steer the schooling ship.

The tests drummed up similar controversy and criticism as in the US. It was mostly around them being a political and negative control mechanism, and their distorted critique (of what goes on in schools), waste (with regard to classroom time spent teaching to the test) and misclassification (reflection of the students’ socioeconomic circumstances rather than learning).

Read more: A year without NAPLAN has given us a chance to re-evaluate how we gauge school quality

These came alongside confidence the tests can help diagnose learning gaps and keep parents, researchers and policymakers informed of students’ performance.

But NAPLAN’s cancellation during the 2020 COVID pandemic, as well the hiatus of standardised tests in other countries like the US, has made interested parties question whether it may be the beginning of the end of the obsession with the testing method.

Where to now?

Some successful education nations like Finland — which rank highly in international standardised tests like PISA — avoid external, national standardised tests.

Finland has been a poster child for school improvement since finding its way to the top of the international rankings after emerging from the Soviet Union’s shadow. The country has magnificently shifted from a centralised education system, that celebrating external testing, to a more localised one in which highly trained educators provide more narrative feedback to students.

As the Finnish policy analyst Pasi Sahlberg explains, Finland has made a conscious decision to avoid investing in standardisation of curriculum enforced by frequent external tests.

Instead, it focused on teacher education and providing time for teacher collaboration on issues of instruction. Student-free daily meals, health care, transportation, learning materials and counselling are also part of the package.

With the ongoing conversation about quality, possible assessment alternatives and new ways of schooling, only time will tell whether standardised testing programs continue shaping Australian and international education practices.![]()

Ilana Finefter-Rosenbluh, Lecturer, Faculty of Education, Monash University

This article is republished from The Conversation under a Creative Commons license. Read the original article.

Read LessACPPAConnect - Have you had a look?

You may remember, late last year we launched our new Principal Health and Wellbeing portal, as a direct a result of our strategic planning based on your needs and requests.

This MEMBER ONLY, dynamic wellbeing platform is a member benefit with a focus on advocacy and action for Principal mental health and wellbeing.

Your health and wellbeing is important and we want every Principal to thrive and be supported as you lead your school communities.

Watch the ACPPAConnect launch video here:

Go to our ACPPA webpage and click on the ACPPAConnect button in the top right corner. ACPPA Homepage

If you are a Principal, use your password to login and have a look around, use the resources and tell us what else you want to see on the ACPPAConnect portal.

Email paul.colyer@acppa.catholic.edu.au if you have forgotten your password.

Our aim is to ensure that ACPPAConnect is driven by your needs and we would appreciate lots of feedback.

I encourage you to explore the portal now and over the coming weeks.

This is for you and we hope you like it and find it useful!

PAUL COLYER - Australian Catholic Primary Principals Association

Phone: +61478973767

Email: paul.colyer@acppa.catholic.edu.au

5 min read

Can an employer compel employees to get the COVID-19 vaccine?

Australia's COVID-19 vaccine rollout has begun. The Commonwealth Government's goal of offering everybody in Australia a vaccination by the end of October 2021 raises an important ethical and legal issue for Catholic primary school Principals to navigate during these turbulent times; that is, can staff members be forced to have the vaccination?

What is a lawful and reasonable direction?

All employment contracts contain a term implied by common law which requires the employee to obey the lawful and reasonable directions of the employer. The implied duty of obedience imposed on all employees is subject to the express terms of the employment contract and any applicable workplace instrument (e.g. modern award or enterprise agreement).

A ‘lawful’ direction is one that falls within the scope of the employment contract and does not fall foul of the law.[1] An employee has the right to refuse to carry out any directions that are unlawful, including:

- Directions to engage in unlawful behaviour;

- Directions to engage in dangerous behaviour that would create a risk to health and safety;

- Directions to engage in conduct that is contrary to the employment contract and/or applicable workplace instruments.

A ‘reasonable’ direction is one that is sensible, logical and/or rational having regard to the individual circumstances of each case. There is no obligation on the employer to demonstrate that the direction was preferable or the most appropriate course of action or in the best interests of the parties.[2]

Any breach of the implied term will constitute breach of contract for which the employee may face disciplinary action, including summary dismissal if the breach amounts to ‘serious misconduct’.

COVID-19 vaccine

The question that arises in the context of the current global pandemic is whether employers have the power to force employees to take the vaccine; that is, is directing an employee to have the vaccine a lawful and reasonable direction?

One relevant consideration would be an employer’s obligation under relevant State and Territory legislation to provide and maintain for employees a working environment that is safe and without risk to health. These obligations commonly include, amongst other things, an obligation for employers to reduce or eliminate as far as practicable, risks to the health and safety of employees. Accordingly, it could be argued that an employer’s work health and safety responsibilities extend to requiring staff vaccinations, especially as the country continues to struggle with containing outbreaks in workplaces.

Whilst no case law exists on this novel issue, a recent Fair Work Commission case provides an indication on the direction this issue may take in Australia. The matter of Kieran Knight v One Key Resources (Mining) Pty Ltd T/A One Key Resources [2020] FWC 3324 involved an unfair dismissal application by employee who was terminated for failing to follow a lawful and reasonable direction to complete a COVID-19 survey regarding travel information. The Fair Work Commission found that the employer’s direction was lawful and reasonable because the information requested in the survey was not sensitive or protected by privacy laws and the survey was for the purpose of attempting to fulfil its obligations under workplace health and safety laws. As such, the employee’s refusal to complete the survey constituted a valid reason for the dismissal.

Implications

Whether an employer has the power to compel their employers to get vaccinated against COVID-19 has not been clearly stated. In the absence of a government or Health Department directive, employers will generally not have an unfettered right to require their employees to be vaccinated against COVID-19 but this space will likely evolve rapidly over the coming months.

Despite this, the potential consequences are grave for an employer who gets it wrong. It is hoped that the Commonwealth Government will legislate to provide clear direction on this issue. In the meantime, employers must be aware of the possible legal and moral ramifications of directing mandatory vaccinations in their workplace and of taking disciplinary action and/or dismissing any employees who fail to follow such direction. What is the situation if the employee refuses for medical reasons? What is the situation if the employee refuses for religious reasons? What if the employee refuses purely on the basis of anti-vaccination beliefs? What do you do if a staff member refuses to return to work out of fear of contracting COVID-19 from unvaccinated employees?

Employers may be exposed to unfair dismissal claims under the Fair Work Act 2009 (Cth) (on the basis that any termination was harsh, unjust or unreasonable). Furthermore, given the potential human rights concerns at play, employers may be exposed to general protections claims under the same regime (on the basis that any termination or other adverse action was taken for discriminatory reasons such as religion or political opinion) or a discrimination complaint pursuant to the relevant State and Territory anti-discrimination legislation.

[1] Grant v BHP Coal Pty Ltd (No 2) [2015] FCA 1374

[2] Briggs v AWH Pty Ltd [2013] FWCFB 3316

How Brennan Law Partners can assist

We recommend that you get proactive on this issue whilst waiting for further guidance from the relevant authorities, including governments and educational institutions. It would be prudent to consult with staff, and have decisions made and plans in place so that you are appropriately positioned when the vaccine rollout commences.

If you would like to know more about how these issues are likely to effect your school or would like our assistance to draft relevant correspondence or policies, contact us to discuss.

Click the logo to find out more

Read Less

Daniella J. Forster, University of Newcastle

As an educational ethicist, I research teachers’ ethical obligations. These can include their personal ethics such as protecting students from harm, respect for justice and truth, and professional norms like social conformity, collegial loyalty and personal well-being.

Moral tensions in schools can come about when certain categories of norms conflict with each other. For example, sometimes students’ best interests are pitted against available resources. These present difficult decisions for the teacher, the school community and its leaders.

As part of a global study on educational ethics during the pandemic, I conducted focus groups with Australian childcare, preschool, primary and secondary school teachers to find out what ethical issues were most pressing for them.

Below are three ways in which the pandemic highlighted existing tensions between ethical priorities.

1. Student well-being versus learning

The Australian Professional Standards for Teachers emphasise student well-being is important to learning. But they note teachers’ main priority is making sure the student learns at their stage of the Australian National Curriculum.

During COVID, this flipped and well-being took precedence. A primary school teacher told me:

It’s the first time in my teaching career where the learning became a low priority, and well-being took over … if we could keep them chugging along, that was good enough.

An Aboriginal-identifying teacher who shared their strong cultural background with students said:

… a lot of the Aboriginal students … didn’t have access to … resources. And so there was already this disconnect that became even wider by the time they had to learn from home … Some students were not able to complete the work that I was putting on the online forum because they were caring for little brothers and sisters when they were at home … or home life was extremely volatile …

A secondary school teacher said:

There were certain students that we were made aware of by the well-being coordinators that we weren’t to make contact with. If there were more extenuating circumstances in the life of the child then we weren’t to … exacerbate that by sending emails home about them not completing work …

Some teachers found it particularly difficult to identify students at heightened risk and to put in place their duty of care requirements.

Read more: 'The workload was intense': what parents told us about remote learning

A public primary school principal in a low socioeconomic area said:

We had a couple of instances where we would have had more contact with family, community services and since (then) we have heard stories of what happened when the children weren’t coming to school … we would have made an instant call to DOCS [Department of Community Services], but because we weren’t having that day to day contact we didn’t know. A lot of those things were hidden, very serious issues.

2. Government policy versus staff well-being

Leading teachers and principals found the tension between their personal safety and that of their colleagues were often in conflict with a lag in institutional directives.

For instance, on March 25 The NSW Teachers’ Federation urged the education department to immediately prioritise the safety of staff and students.

But the department took time to mandate social distancing measures, school closures and learning from home. In the meantime principals were on alert for risk management, anticipating directives for extensive social distancing, such as cancelling school assemblies, before being instructed to do so.

One public school principal said:

The federation is telling us this. The department is telling us that … I would make a decision and then a couple of weeks later … the department would come up with the same strict instructions … it was the well-being of the staff first for me … even to the point where we sent the kids home for the first week with no learning … the second that one child comes to school and catches COVID, then I’m not going to be able to live with myself.

But it wasn’t the same in all schools. A primary school teacher in a bushfire affected area reflected on the decisions made by the principal.

I’m trying to be diplomatic … We were very slow to engage with kids who were starting to be kept home from school. And we were very slow for teachers to be able to work from home and we were very quick to come back to … school … We have a parent who worked at the local high school saying, ‘Oh, yeah, we’ve been working at home all week’. We haven’t even been told that’s a possibility …

3. Personal well-being versus professional integrity

A teacher’s professional integrity is how they evaluate the alignment between the expectations of their role and their values. When a schism arises, it throws into question some core professional values.

One public school principal’s integrity had an extremely high bar.

I’ll be really honest, despite all of the warnings and all of the advice, my own well-being was my last priority. And the ethical dilemma for me was, I can’t look after myself because I’ve got so many other people to look after first, despite all the warnings, despite all the advice.

Teachers reported the personal cost of changing work arrangements into remote settings, concerned about how they were to fulfil their professional integrity to provide the kind of meaningful interactions students needed.

A secondary Catholic school teacher said:

Remote learning really threw me off balance and I struggled to find myself and how I fit into that situation … I had to learn to let go and … work out what is really important.

For the next generation of teachers, the dilemma was more about how to set boundaries in an emerging professional identity.

One early career public secondary teacher said:

I did go out of my way to with my Year 11s, them being my most senior year … Which did bring up the ethical thing … there were times I would get a message at one o'clock and I’d be up but I’d say, I’m not answering that, I’m not looking at it. I’m looking at it in the morning. That’s too much in each other’s heads. And, yeah, the barriers were tough.

An experienced secondary teacher in an International Baccalaureate school said:

I was working sending emails at midnight, and getting up three hours before my lessons to try and make sure that the platform is working … and obviously all my lessons that I plan had to be then turned into online lessons. So that takes a whole other weekend for everything … I got WhatsApp messages at all hours …

She said students sent her emails to thank her for the commitment. She realised it was a toxic message to send, and that implied this should be the norm for teachers. While teaching is a generous profession, COVID highlighted the expectations on their generosity.

Read more: 'Exhausted beyond measure': what teachers are saying about COVID-19 and the disruption to education ![]()

Daniella J. Forster, Senior Lecturer, Educational ethics and philosophies, University of Newcastle

This article is republished from The Conversation under a Creative Commons license. Read the original article.

Read LessSupporting children learn resilience through adversity

In a year of change and uncertainty, schools have consistently provided a safe and supportive haven and community hub for many children and their families. In the past year, Catholic schools and their staff have been called upon to support students and families experiencing a range of emotions and reactions to challenges that have been sustained and unprecedented. We have heard and witnessed the concerns from many teachers and counsellors also regarding the additional changes faced by many children and young people – separation and divorce, limited access to grandparents and other support networks.

We hope that our Stormbirds and Seasons for Growth programs have assisted school principals and teachers to help students navigate their feelings and provides them with an opportunity to develop knowledge, skills and resilience for their experiences now and for those they will encounter in the future.

Stormbirds has been funded in many bushfire impacted communities, providing an opportunity for children and young people who have experienced a natural disaster to share their experiences of change and loss in safe and creative ways, understand and attend to their feelings, and learn skills for adapting and recovering.

In response to Covid19, we transitioned all our training for Seasons for Growth online and we continue to offer the training to support children and young people with their varied experiences of change and loss. We have funded places available for professionals working who can commit to supporting children and young people with the program. We have funded training available on our training list. Read more

Over the past 25 years, our programs have supported over 300,000 children and young people in Australia and internationally - we hope that participation in the programs has supported children and young people to respond to their experiences of change and loss, and support them to be in a place to engage with their peers and engage in their learning.

Programs like Stormbirds and Seasons for Growth bring expertise and add value to a busy curriculum while focusing on student welfare and promoting resilience and connection for the whole school community.

To find out more about Seasons for Growth and Stormbirds, contact by email Godelieve

Check out the:

Seasons for Growth helpful factsheets and resources for you to explore, download and share with your community.

The need for mental health education in Australian schools

7 min read

The disruption and stress of 2020 resulted in a spike in mental health problems that are likely to continue into 2021.

Mental illness accounts for 16% of the global burden of disease and injury for youth aged 10-19. One in seven Australian young people are affected by a mental disorder, with a recent report finding that Australian youth were five times less likely to seek help at times of psychological distress.

Mental illness in young people can affect core areas such as education, achievement, relationships, and occupational success. The prevalence of mental health concerns has increased among children and adolescents due to the COVID-19 pandemic, with mental health services struggling to keep up.

A Headspace report conducted during the peak of the COVID-19 pandemic found approximately one in three young people experienced high levels of psychological distress. In Victoria, there was a 72% increase in 2020 of the number of serious self-harm and suicidal ideation presentations in emergency departments for young people, and an increase of 23% of mental health concerns presented in emergency departments compared with the previous year.

These statistics show the disturbing incline of youth mental health problems, highlighting that more effort is needed for support and prevention.

Read more: Now is the time for a paradigm shift in how we treat mental ill health

Stigma towards mental illness, and a lack of mental health education, present a barrier to youth seeking help for mental health problems. However, research suggests that young people want to learn about mental health and coping strategies in school.

Mental health encompasses more than mental illness; it includes educating people on how to nurture mental wellbeing, and seek help if necessary.

As the World Health Organisation states: “Mental health is a state of wellbeing in which an individual realises his or her own abilities, can cope with the normal stresses of life, can work productively, and is able to make a contribution to his or her community.”

In this sense, mental health collectively includes prevention, promotion, and treatment. Until recently, mental health has followed a medical model, mostly associated with illness and treatment, rather than prevention and promotion.

Mental health literacy

Mental health literacy has evolved in the past 20 years since first proposed by Anthony Jorm, and refers to knowledge of mental health (including how to promote positive mental health), and help-seeking/treatment options.

Components of mental health promotion and prevention programs such as learning about coping strategies, mental health problems, and increasing self-efficacy and resilience are aspects of mental health literacy that are associated with improved overall mental health.

When considering the high prevalence of mental illness in children and adolescents in Australia, it seems logical to focus on preventative approaches incorporating mental health literacy.

There’s a need to move away from the narrow focus on absence of mental illness, and towards promotion of positive mental health. This could equip children and adolescents with tools and knowledge that may potentially decrease the prevalence of mental illness in the future.

Schools provide a safe learning environment

Schools have been established as an optimal space for learning, and young people spend the majority of their time in school. Therefore, incorporating mental health literacy programs in schools could solve issues of transportation and access that often inhibit young people’s involvement in such programs.

Experts say mental health should be a priority in schools in 2021. The Mental Health Practitioners initiative began in July 2019, and provides funding to Victorian public schools to employ a mental health practitioner. This is part of the $65.5 million investment from the Victorian government in student health and wellbeing initiatives in schools.

Read more: Mind gains: Time to expand the offering of psychology study in schools

Schools provide an optimal setting for health promotion initiatives for children and adolescents, so why is there a lack of school-based mental health education?

Some leading researchers in the field have called for mental health literacy research to link with how to change help-seeking behaviour and improve mental health. Many propose this be a widespread goal to increase the uptake and acceptability of mental health literacy among the population.

Research shows that teachers/educators lack confidence and training to effectively support child and adolescent mental health. Additionally, studies of school-based programs targeting mental health literacy for children and adolescents are limited.

Here’s how we can support the mental health of young people

Mental health literacy programs need to be implemented and evaluated for youth to increase the evidence base supporting programs within the Australian setting. International studies, such as the evaluation of the Youth Education and Support program in the US have found promising results on increasing mental health literacy for youth in an educational setting.

While teachers may not have the time or competency to deliver such a program, mental health practitioners placed in schools may have capacity.

Read more: Mental health and the coronavirus: How COVID-19 is affecting us

The recognition of the need for mental health support in schools, and investment from the government is a step in the right direction, though currently school-based mental health literacy programs appears to be a neglected opportunity. Educating young people through mental health literacy programs in school with a preventative approach could lead to positive mental health and better life outcomes.

Our research team in the Faculty of Education at Monash is seeking to do just that – we aim to examine and validate a youth-centred school-based mental health program.

Young people’s experiences and knowledge of mental health and wellbeing are at the heart of the prevention program that will be established to suit the Australian context responding to the increase in youth mental health challenges during and post-COVID-19.

This article was first published on Monash Lens. Read the original article

Read Less

Connecting with others remotely: What have we learned from online learning?

10 min read

The importance of teacher-student relationships in the classroom, and the impact it has on students’ success, is acknowledged. Remote/online learning – in primary, secondary and higher education institutions – has challenged how we’ve traditionally created strong relationships and positive learning environments.

Yet, those learning environments – whether face-to-face or online – are created by people. They cannot be replicated with the click of a button, and they can’t be standardised. They’re uniquely crafted, imbued with emotion and humanity, built through, and utterly dependent upon, relationships.

As four lecturers from Monash’s Faculty of Education, we reflect here on our experiences of teaching in an enforced online situation – how we attempted to address teacher-student relationships, and maintain connections with our students.

The world of online relating is here to stay for the foreseeable future. Our lessons from the online classroom provide insights for all of us as we seek sustainable ways to connect with teachers, students, work colleagues, family members, and even blooming romances.

We introduce four principles, drawn from our online teaching experience, for how to approach online relationships: acting with intention; humanising the online experience; attending to emotions; and bringing ourselves to the online space.

Acting with intention

The relative ease of relating in person is missing online. We can’t read the Zoom room as accurately as we can the physical room. It’s more difficult to convey warmth and welcome. What emerges in-person mostly effortlessly – from a smile or glance – now needs to be created. With intention.

We need ways to convey the taken-for-granted bits. As the teacher, there’s benefit to surfacing and naming what’s behind our pedagogical actions, as well as attuning our ear more intentionally to what our students have to say, while we recognise – in perhaps more honest ways than in person – that we can’t have the whole picture.

As an example, circle discussions can be facilitated, with students named as co-creators of knowledge. Students pass the microphone person-to-person to share their experiences and insights on the topic in question.

Online relating requires us to proactively name relationships as central – to whatever activity we’re undertaking – and to build in explicit ways to nurture connection.

Humanising the online experience

In teaching, it’s important to connect what students are learning with their life experiences and the world around them. This makes learning both relevant and personal.

With the transition to online learning, we knew some students would struggle to engage. In order to humanise students’ online learning experience, an effort was made to provide opportunities for students to connect, share and “talk”, linking their personal experiences with what they were learning.

Read more: We are with you: Parents share their teaching and learning lessons from the lockdown

Students were provided extra opportunities to “talk” and connect in a range of interactive platforms. Variety has been key in order to satisfy student learning preferences – providing both one-on-one consultations with their teacher, small-group discussions with peers (with or without the teacher), online discussions, and social media discussions.

COVID-19 has impacted our daily routines and human interactions – the very things that used to make us feel normal. However, we’ve learnt that our online experiences can provide valuable opportunities to meaningfully connect with others – if we choose to create the space for them.

Attending to emotions

As we seek to humanise online spaces, emotions cannot, and should not, be ignored. By attending to emotions, we can maintain meaningful connections within the virtual space.

From the beginning of our teaching, we noticed that our students’ emotions were directly and indirectly impacted by the COVID-19 crisis, which in turn influenced their learning and connections in the online platform.

It was important to acknowledge these emotions and carefully plan them into the lessons, rather than treat them incidentally.

At the beginning of the tutorials, students would share their emotional states through an informal anonymous survey, which gave them the message that we cared about them and their emotional states. Running the same survey at the end of the tutorial helped students become cognisant of any positive changes in their emotions.

It was also a chance for us to see if we had been effective in creating changes by discussing or acknowledging any high-running negative emotions communicated at the beginning.

Bringing ourselves to the online space

Teaching online through a narrow Zoom portal, often talking “to” black squares with a series of student names emblazoned across the screen, no way of knowing who’s engaging and listening, who’s sleeping and snoring…

While many of our students are hidden from the teacher’s “gaze”, as a teacher trying to facilitate online learning, we found reorienting our teacher personality online the biggest struggle.

Initially, we found focusing on the content and online activities with which we were trying to engage students lacked the spontaneity and personality developed over years of face-to-face teaching. It took several months of online teaching to realise that was a key missing variable of the online teaching – us!

Read more: Inclusive education during COVID-19: Lessons from teachers around the world

Whatever online space you’re engaged in, it’s imperative your online presence isn’t reduced to a generic and anonymous persona – allow your personality to be present, however that might look for you.

COVID-19, in its upheaval of our usual ways of relating, has made us acutely aware of the nature and quality of our connections.

As we, as lecturers, have navigated through these past months of online learning, we offer these insights for all our online relationships – with intentionality, keep the online space human by bringing a sense of self and attending to the emotions of those within the environment.

This article was first published on Monash Lens. Read the original article

Read Less

Young Voices Award - Jesuit Communications

Australian Catholics Young Voices Award is open to all students around the country, having evolved from the Young Journalist Award, run through the magazine for the past 25 years. The Awards this year expand to recognise a wider range of media including poetry, photography, video and audio as well as written-form journalism.

Sponsored by long-time YJA sponsor Australian Catholic University (ACU), the Awards give primary and secondary schools students around the country a voice - and the opportunity to be published in the largest circulation Catholic print publication in the country. Winning entries also feature on Australian Catholics digital channels.

Entries close at 5pm, Friday, 28 May 2021.

Toolkit for Schools | eSafety Commissioner

The eSafety Toolkit for Schools is designed to support schools to create safer online environments.