Filter Content

- From the President

- An awesome inspiring message from Cam Calkoen

- Australian Catholic Super

- The 3Ts - A phased approach to leading through crisis (AITSL)

- ACPPA Welcomes Catholic Church Insurance

- Mindfulness Inspiration and Techniques

- WOODS Furniture

- Children as content creators: 'Learning by doing' during the pandemic using technology

- ACARA Updates and Video

- Camp Australia

- The Breakthrough Coach

- 'Exhausted beyond measure': what teachers are saying about COVID-19 and the disruption to education

- GOOD GRIEF

- Online Resources from ESA

- MSP

- Should you hold your child back from starting school? Research shows it has little effect on their maths and reading skills

- Switch Education

- Just a thought!

Over recent months we have all been challenged by the circumstances presented to us through the COVID pandemic. The conversations I have had with both Board members and Principals in schools makes me realise that the resilience and strength in our leaders is very evident and appreciated by school communities. Keep up the great work and remember to care for yourself as we move through the second half of the year.

We held our most recent Board meeting this week, again via zoom.

Some points of interest:

At the meeting we progressed work on our new Principal Wellbeing Portal which will be a repository of free resources and links to assist principals to manage their health and wellbeing. Stay tuned for more updates on this great initiative.

We have also now completed the final design of our new ACPPA LOGO which will be launched at our AGM on 9th November via zoom. This is a very exciting step for ACPPA and we encourgae you all to tune in at the AGM. Invites will be sent soon.

During my report I shared a number of important updates:

- the ongoing impact of COVID -19 on schools and the economy

- the school visits being undertaken by ACARA as part of the F-10 Curriculum Review

- a number of ACPPA Directors have been a part of the AITSL Roundtable discussions regarding teacher abuse, esteem of the profession and Principal wellbeing.

A word from our valued Partners at Catholic Church Insurance and WOODS Furniture

It was again great to be able to hear from our partners, Hugh Easton at CCI and Greg Barnes from WOODS Furniture, who zoomed in to give us an update on how recent events have impacted on their organisations. In these times of virtual meetings it was good to connect and touch base with our supporters.

An awesome inspiring message from Cam Calkoen

Here is the final video message in our series to show support for all of you and the work you have been tirelessly doing in your communities during these difficult times.

We are honoured that New Zealand based Cam, who has had connection with our Principals in the past, offered his support to share his thoughts and help us visualise our dreams.

The 3Ts - A phased approach to leading through crisis (AITSL)

10 min read

A crisis is defined as a difficult or dangerous situation that requires immediate and decisive action. Crises are not the normal recurring challenges that schools experience on a day-to-day basis. Rather, crises are usually ‘confronting, intrusive and painful experiences’ (Smith & Riley 2012, p. 53), at least for some members of the school community. Crises of one form or another will inevitably occur in all schools, no matter how well the school is led.

There is no neat blueprint for leadership in such times, no pre-determined roadmap, no simple leadership checklist of things to tick off (Harris 2020).

The critical attributes of school leadership in times of crisis include:

- The ability to cope and thrive on ambiguity.

- Decisive decision making and an ability to respond flexibly and quickly and to change direction rapidly if required.

- A strong capacity to think creatively and laterally and question events in new and insightful ways.

- The tenacity and optimism to persevere when all seems to be lost.

- An ability to work with and through people to achieve critical outcomes, synthesising information, empathising with others and remaining respectful.

- Strong communication and media skills (Smith & Riley 2012).

Lessons from other sectors suggest that breaking down the broader challenge into phases may help leaders move forward without becoming overwhelmed by the scale of the problem.

In this way, the 3Ts is a framework that may be useful for schools: Triage, Transition, Transform (Lenhoff et al. 2019). The 3Ts can be used to reflect on a crisis situation, both during and after the event. This framework is not linear, for example, while moving through a later phase (transform), leaders may also be helping others in an earlier phase of the crisis (transition). The value of this model is to provide a lens for understanding the types of challenges leaders may face at each phase of a crisis.

Reflective questions to learn and grow as a leader

These questions on Triage, Transition, Transform and Wellbeing can guide school leaders and their leadership teams through the process of reflecting on a crisis response.

1. Triage

Triage refers to an initial sorting process on the basis of urgency. The task in the immediate onset of a crisis is to separate the now from the later. At this stage, adrenaline is high, there are plenty of practical things to take care of, and the leadership approach most likely to be selected from the school leader’s toolkit is authoritative leadership. Taking decisive action, the focus is on safety and wellbeing for everyone who is immediately affected. For school leaders this could mean rapidly sharing up-to-date government advice to school communities and proactively implementing changes in their schools.

Accounts from schools directly involved in the Canterbury earthquake in New Zealand, show school leaders taking control while remaining focused on creating a calm atmosphere.

Leaders in schools and early childhood services became role models for others. If the leaders stayed calm, then children, staff and parents were more likely to remain safe and calm (Education Review Office (ERO) 2013, p. 1).

While ensuring physical safety is the absolute first priority, psychological safety is also important. People need to feel safe to ask questions, raise concerns, and propose ideas. Transparency and open communication help build a better understanding of the full picture.

Transparency is ‘job one’ for leaders in a crisis. Be clear what you know, what you don’t know, and what you are doing to learn more (Edmonson 2020).

Transitioning from the triage stage, and carrying learnings forward, requires strong leadership. A key consideration for education leaders at this point is how to ensure learning continuity.

2. Transition

Once lockdown or evacuation is over, and people’s basic physical and security needs have been attended to, the leader’s focus is to increase stability, and reduce uncertainty for teachers, other school staff, students and their families.

The phase of transition is about adopting new ways of working and being, be it for a short time or a more extended period. After immediate responses to dangers or threats have been actioned, communities are often adjusting to new approaches. This may involve a dispersed school community, or a move to relocatable buildings, as well as replacing lost materials. For example, in the context of the current pandemic, this phase has involved a combination of remote learning and a transition back to socially distanced classrooms.

A further example can be drawn from the school closures in Hong Kong during the protests in 2019. David Lovelin from Hong Kong International High School provided the following leadership advice for managing such a crisis (Jacobs and Zmuda 2020):

- Establish a crisis management team.

- Use talent within your school community.

- Identify key common technology platforms for communication.

This advice, born out of this Principal’s experience, reinforces the evidence-base on effective leadership through change, which emphasises the importance of teams and communication.

Mobilising teams and expertise

The complexity of the challenges leaders face demands solutions that reach beyond one individual. Rather than looking to individuals to solve problems, people increasingly recognise that effective solutions come from networks and other collaborations (Jensen, Downing & Clark 2017, p. 20).

Leading through complexity requires working together to draw on the collective wisdom of the group to find solutions to the challenges presented. A collective approach to leadership is essential for the sustainability and wellbeing of leaders, teachers, schools and the broader education system. Distributed leadership is an approach that recognises multiple people influence improvement in a school, including middle leaders (Harris & Spillane 2008). A growing body of evidence on the power of shared leadership has found that it:

- Creates a more democratic organisation.

- Provides more significant opportunities for collective learning.

- Provides opportunities for teacher development.

- Increases the school’s capacity to respond intelligently to the many and complex challenges it faces (Leithwood 2012).

Collective impact

When working through complexity, leaders can mobilise their teams by setting clear priorities for the response and empowering others to discover and implement solutions that serve those priorities (D’Auria & De Smet 2020). This requires fostering collective and collaborative leadership capacity and acknowledging the impact of the collective. Collective impact is recognised in the area of social impact as a collaborative approach to addressing complex social issues (Kania & Kramer 2011; Cabaj & Weaver 2016). There are five conditions that produce alignment and move people from isolated agendas, measurements and activities to a collective approach and impact:

- A common agenda.

- Shared measurement.

- Mutually reinforcing activities.

- Continuous communication.

- Backbone support.

Leadership in a crisis should be collaborative but should also look to be sensibly hierarchical. There are times when school leaders need to wait and take advice from government, system-level leaders and first responders. Within the school, a well-formed crisis management team brings a cross-section of perspectives to a problem, and reduces the risk of missing certain voices.

Some in the school community have specific expertise and leadership responsibilities because of their role. Staff with professional qualifications beyond education such as the school counsellor, psychologist, nurse or chaplain, and information and resource specialists in the school’s library have additional skills to contribute in such situations. Information technology staff become heroes when remote schooling scenarios come into play, and cleaners and facilities staff bear the brunt of restoring sites post-disaster. Supporting the supporters is a key element of a school’s emergency management and recovery plan (Whitla 2003). Tapping into expertise and influencers in the parent body, local personalities and networks can also support the school’s leadership team.

Clear and open communication

Communication is vital. In the aftermath of the Canterbury earthquake, New Zealand leaders highlighted their need for communications systems that operate when people have no access to an office, school computer or power (ERO 2013). In an information age, the issue leaders face is often not a lack of information, but an overwhelming amount. The apparent wealth of communication channels can actually hinder free flow of vital information. In the same way we look to the Australian Broadcasting Corporation as our national emergency services broadcaster, schools that establish a common, official communication channel, and ensure up front that everyone in the school community can access this readily, are better equipped when the need arises.

Clear, simple and frequent communication is imperative to sharing up-to-date information and maintaining open communication channels. In fact, school leaders, who are themselves a key communication channel may benefit from media training (Smith & Riley 2012). Both verbal and written communication are important. In a school context this includes newsletters, assemblies and information sessions for lengthier communications, and the use of instant messaging systems, quick pulse surveys, daily staff meetings or bulletins, and wellbeing check ins.

3. Transform

Rebuilding school communities after major disruption and trauma requires a rethinking of social capital, resilience, of space, individuals’ roles and their contributions (Nye 2016, p. 88).

Leading the recovery of a school community after a crisis involves a delicate balancing act. Key findings from the aftermath of crises such as Hurricane Katrina in New Orleans and the Canterbury earthquake suggests that for schools, recovery may be less about minimising the loss of student learning time and more about the role schools play in emotional and social recovery, which can minimise longer term health concerns (Hattie 2020). During this phase the needs of those impacted by the crisis must be sensitively balanced with the community’s (staff, students and parents) desire to return as quickly as possible to business as usual routines.

Through this phase of transformation, schools may act as:

- community drop-in and re-bonding centres.

- pastoral care and agency hubs for staff, students, and families.

- frontline screening to identify community members experiencing severe effects.

- facilitators of appropriate recovery services (Mutch 2014).

Rebuilding during the transformation phase provides an opportunity for leaders to adapt “flexibly and strategically to changes in the environment, in order to secure the ongoing improvement of the school” (Professional Practice: Leading improvement, innovation and change, AITSL 2014, p. 17). In this phase, schools have a chance to refocus, re-energise and try new ideas (Smith & Riley 2012, p. 64). This involves learning and growing from the experience, and possibly experimenting with a new vision, values and culture. In this way, the recovery period can become an opportunity for transformation – to ‘build back better’ (BBB) by integrating disaster reduction and management strategies into the ‘restoration’ and ‘revitalisation’ of systems and communities to build resilience for future crises (Global Facility for Disaster Reduction and Recovery n.d.; United Nations General Assembly 2016). For example, the current COVID-19 pandemic demonstrates that rebuilding is not only about physical infrastructure, but about the health, safety and wellbeing of individuals and school communities.

Determining what has worked and what hasn’t and deciding what to cut, keep or further develop are key considerations to support learning and growth following a crisis. That is, the period of transformation is also about retaining any successful new practice that emerged during the crisis, to build the ‘new normal.’ An important role for school leaders in this process is to broker agreement on what ‘building back better’ or the ‘new normal’ should look like, ensuring it centres on the needs of students (Mutch 2014). Taking the time to reflect and learn from a critical incident is, therefore, an valuable exercise, both in terms of ensuring the school leader’s voice is part of the review that will inevitably follow a crisis or incident, and as an optimal time to revisit a school’s disaster/crisis policies (Myors 2013

Read LessACPPA Welcomes Catholic Church Insurance

It is with great pleasure that we annnounce a new 3 year partnership with Catholic Church Insurance (CCI)

Thanks to Hugh Easton, State Manager (QLD) for his work with ACPPA to bring this to reality.

Children as content creators: 'Learning by doing' during the pandemic using technology

5 min read

Instructional design in education - that is successfully designing what a student will learn and how they will learn it, both online and physical - is currently experiencing unprecedented attention and growth, which could prove to be one of the best things to come out of the chaos caused by the COVID-19 pandemic. All educators who are planning and preparing lessons for students to learn at home will be currently grappling with Instructional design.

Parents, faced with helping their children learn from home, are also increasingly involved with how learning takes place using technology.

‘Learning by doing’ using technology

South African-born American mathematician, computer scientist and educator, Seymour Papert, generally regarded as the father of educational technology, was one of the first people to see the potential for technology to enhance learning. He saw computers as an exciting new way to build on the established principle of learning by doing. Papert and his team from the Massachusetts Institute of Technology created opportunities for children to become lessons planners, coders, graphic designers, narrators, and to develop all of the associated skills required to construct learning artefacts. The idea of involving children so directly in their own learning seems radical, even by today’s standards, but never before has the need for authentic learning tasks been so closely matched by the abundance of technology available in most homes.

So what does the role of the teacher look like in this student-centred model? Alison King’s seminal (1993) article From sage on the stage to guide on the side captured this perfectly by writing about how teachers can move away “from being the one who has all the answers and does most of the talking toward being a facilitator who orchestrates the context, provides resources, and poses questions to stimulate students to think up their own answers”.

But this it is a difficult transition for those who see their role as delivering content. Most of us have Google in our hip pockets or handbags where you can literally search for anything but what are we to do with the multitude of answers that we are presented with? Clearly, information is not synonymous with knowledge or learning. Complexity is not something to fear but the current shake up of the whole education system presents some promising possibilities if we choose to embrace them at each level of the educational hierarchy. Perhaps it is this hierarchy that presents the promising potential for change.

The trouble with ‘back to basics’ mantras

Educational policy makers and government decisionmakers need to stop espousing fundamentalist mantras such as ‘back to basics’ as this is a paradox which is clearly not working. Perhaps a musical analogy is apt here. Musical scales are the building blocks of songs but imagine asking musicians only to focus on perfecting their scales. Training musicians in this way and then putting them on a stage would leave an underwhelmed audience as the basics are only a means to an end.

Are children truly capable of becoming content creators?

There is plenty of research to show that such higher-level tasks can improve both learning and engagement. Simple practices like encouraging children to add the date into their file names creates a chronology of the learning and an abundance of digital assessment data. The idea of ‘learning by teaching’ has been around since antiquity where Pliny the Younger said that “he [or she] who does the talking does the learning”.

Is this an ideal which is beyond the capability of most students? The ‘guide on the side’ model suggests that children will still require assistance but the nature of the assistance in these scenarios revolves around higher levels of thinking. The four Cs of 21st century skills are the same skills that creating digital artefacts can develop, namely; collaboration, communication, critical thinking and creativity. Now that circumstances are forcing teachers to abandon the teacher-centric model, their own practice is also morphing into instructional design.

Students learn by becoming content creators

My proposal, that students become content creators for the sake of their own learning, also resonates with two other approaches which are widely accepted as best practice, namely, project-based learning and open-ended tasks (tasks where achievement options are not pre-determined allowing learners to respond creatively).

Project-based learning is a move in the right direction as this reflects how adults work and function in the real world. It also does away with a lot of the time that teachers spend explaining standalone lessons and can be likened to a good TV drama where each episode begins where the previous one finished, unlike a movie where considerable time is spent establishing the characters.

Open-ended tasks cater for all students and mitigate many of the challenges involved with differentiation as each student can work at their own level. Another advantage of open-ended tasks is that they are an authentic example of formative assessment where teachers provide guidance throughout the activity rather than just a summative assessment at the end.

I must admit that I feel fortunate to have made the transition from teaching in primary schools into academia where I work with pre-service teachers in the Bachelor of Education at CQUniversity Australia. My role involves working with distance students from all around the country, but what I actually do is basically the same as last year, before the pandemic.

Online lecturers use learning management systems with the functionality to deliver content and manage assessment tasks seamlessly in this online environment. My point is that the higher-level thinking that I do as I prepare and curate online content involves the very same skills that we want our children to have. It is my hope that the children caught in the middle of this transitional phase become the new generation of instructional designers.

Dr Brendan Jacobs works in teacher education as a lecturer at the Mackay City campus of Central Queensland University Australia. He spent most of his career in primary school classrooms before publishing an early example of a multimodal PhD dissertation through the University of Melbourne. Since entering academia, Brendan has published widely in academic journals and spoken at various international conferences about learning and technology. His latest book is titled Explanatory animations in the classroom: Student-authored animations as digital pedagogy. Brendan is on Twitter @BrendanPJacobs

This article was originally published on EduResearch Matters. Read the original article.

5 min read

Top six lessons from MasterChef

Opinion piece by ACARA CEO, David de Carvalho, published in The Daily Telegraph

MasterChef is more than just a reality show – it also has some valuable lessons for students and teachers.

What does MasterChef 2020 have to do with school? More than you'd think.

At the show's Grand Finale, Emilia and Laura were vying for this year's trophy. As I was watching the season, I've noticed some things about the show that are relevant to education – and which parents should keep in mind as they follow their children's educational progress.

So what lessons are there in a reality cooking competition that follow through to the classroom?

The first three relate to the importance of having a knowledge rich curriculum if we want students to think creatively and critically. The second three relate to the role schooling plays in personal and moral development.

Creativity requires knowledge

When contestants are shown the ingredients they have to work with, they have little time to make up their mind what they are going to cook. Within a short period, they must come up with a range of possible ideas that could work, and then select one.

The range of possible ideas depends on what you know about the ingredients: how they taste, the different ways they can be cooked and how long that takes, what flavours go with what. If you don't have that background knowledge in your long-term memory, you're cooked. Creative thinking is not just a case of 'making stuff up' – it requires you to know things.

Critical thinking also requires knowledge

The judges must make fine distinctions of quality between dishes that, to untrained tastebuds, are pretty much the same. They must fairly compare dishes that have different ingredients and cooking methods. This takes expertise, wide and deep knowledge, and experience.

But while Melissa, Jock and Andy might be good at judging food, you wouldn't expect them to be good judges of a diving competition or ask them to decide who should get the Miles Franklin Award. Critical thinking is mostly subject specific. But all good critical thinkers have some things in common, such as paying attention to the relevant details and knowing the right questions to ask.

Order and proportion are the essence of beauty

"The flavours are beautifully balanced," the judges often said in praise of a dish. The beauty was in the balance of flavours, the way they worked together as a unity, not just a collection. This meant that the ingredients had to be in right proportion so that a sauce didn't "overpower", or the texture of the puree was "not too grainy".

In other words, there is virtue in things being done the right way in the correct sequence, and even the most creative dishes have to observe these principles of good order and proportion. Dishes were described as "a work of art", meaning not only was it visually appealing but that it expressed culinary order and beauty. Again, one can't apply these principles unless you have both theoretical and practical knowledge of them.

You can still win when you lose

Many in education worry about the psychological impact on students who don't meet expected standards, about them being "branded a failure". Whether a person is a failure depends on how they respond to failure. For me, whether Reynold won or not, the fact that he chose to cook in a high-risk elimination episode – the same type of fish that he cooked disastrously in an earlier season, leading to his elimination – spoke of his resilience and willingness to learn from his mistakes rather than let them defeat him.

A key question for parents and teachers is how we build resilience in our children and young people so they can experience disappointment and failure without being crushed by it, and adapt to the randomness and unfairness of life and get up when they are knocked down.

Competition encourages excellence

"These guys are all excellent cooks, so I have to bring my best game to the kitchen today." A cliche perhaps, but cliches become cliches because they have an element of truth to them. When we really want to win a prize that others are also striving to win, it pushes us to work harder and smarter. It encourages us to learn more, to develop and refine our skills, to do the best we can.

"You have to ask yourself: is this dish worthy of a final?" All of the dishes prepared by the cooks who made it into the final weeks of competition were good. Many were great. But fewer still were "finals-worthy". People rise to a challenge that is within their ability to meet.

Culture is important

Finally, what distinguishes MasterChef from other cooking shows is the supportive culture created between the contestants. While they are competitors, they are also colleagues. They want to do their best, but they also want the others to do their best. This is not about "beating" others or tearing them down. It's about building everyone up and developing everyone not just in terms of their cooking knowledge and skills, but so they also grow as people. That kind of culture is something every school aims to achieve.

The purposes of education

In this new ACARA web series, ACARA’s CEO, David de Carvalho, reflects on the purposes of education and the fundamental things that make education important.

Visit the ACARA blog to watch

Read Less

'Exhausted beyond measure': what teachers are saying about COVID-19 and the disruption to education

5 min read

Louise Phillips, James Cook University and Melissa Cain, Australian Catholic University

All Victorian school students will be learning remotely from Wednesday. Prior to the state’s premier Daniel Andrews announcing a tightening of restrictions over the weekend, only students in prep to Year 10 in Melbourne and the Mitchell Shire were learning from home.

But on Wednesday, schools will close for Year 11 and 12 students in Melbourne and the Mitchell Shire, as well as every student across Victoria — except for students in special schools and children of essential workers.

Like with the last remote learning period in Australia, the current uncertainty in Victoria might cause disarray and stress among teachers, parents and students.

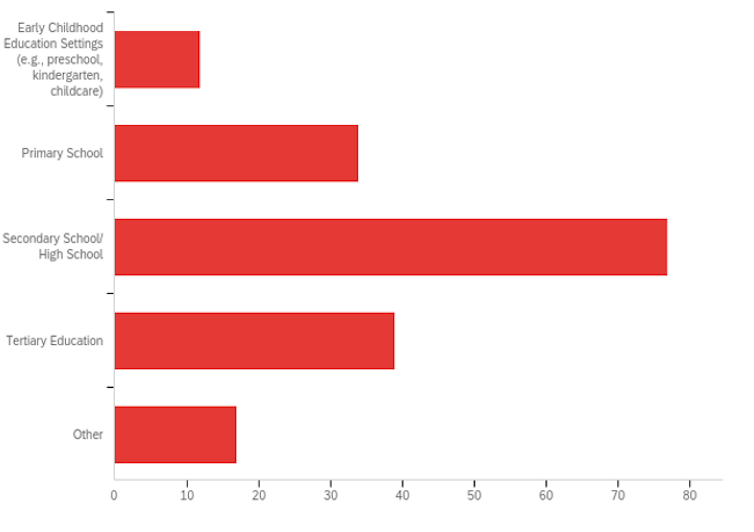

In response to the closures in April, with seven other researchers across Australia, New Zealand, Singapore and the US, we designed a survey that asked teachers 16 open-ended questions about how COVID-19 affected them and their students.

The teachers ranged from early childhood education through to school and university. We also included other educators, such as at museums.

The survey opened on May 4, 2020 while most countries in the survey engaged in home-based learning. There have been 621 responses to date. Of these, 179 are from Australian teachers, with 65% having over 21 years teaching experience, from which this article reports.

Our survey gained rich responses about the sudden closure of schools, transition to online learning, and the difficulties of negotiating social-distancing and increased hygiene maintenance.

Relentless workload

When asked, “How has COVID-19 impacted your teaching and learning?”, responses most commonly referred to technical issues, then the pragmatics of teaching and workload.

Overwhelmingly, teachers from early childhood to higher education experienced a significant increase in their workload. One teacher said the sudden change to online learning created “endless paperwork and programming issues” and “has been relentless”.

Another said

It’s definitely added significantly to my workload and taken the holiday time that would normally provide some respite, meaning I am closer to burnout than ever.

Social distancing requirements also increased teachers’ workload, creating “lots of additional cleaning requirements and having to collect children from the carpark as families are not allowed to enter”.

One teacher said

It is draining. Exhausting. Time consuming. The work never stops.

‘I don’t want to teach anymore’

The impact on the mental and physical health of teachers was the next most frequently expressed — after the technical, pragmatic and workload issues.

One teacher told us:

I struggle to sleep at night for thinking about work all the time. I’m very stressed and anxious; my physical health has been impacted.

Another said:

It has challenged everything I enjoy about teaching.

And another wrote:

All the teachers I work with are EXHAUSTED beyond measure.

Teachers said a lack of voice and agency in decision making made them feel “unmotivated” or “unvalued”.

(we) may have felt more supported had we been consulted and listened to by management and government.

One teacher wrote:

In the beginning, I felt I could have dropped dead at home and my workplace wouldn’t even notice.

Another said:

Going through this, not feeling safe, and then seeing teachers belittled in the media, has made me come to the realisation that I don’t want to teach anymore.

‘It was a scramble’

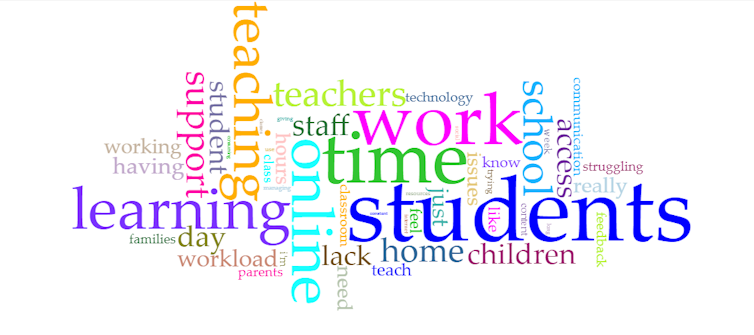

When asked, “What are the issues you are struggling with and need support with?” some teachers mentioned the management and decision-making concerning school closures.

The word cloud below shows the most frequent words in response to the question.

One teacher said:

Our school closed down at the end of term one. It was a scramble and our management made some decisions which made life harder for teachers.

One early childhood and childcare teacher said:

The government has largely ignored the realities of EC [early childhood] environments, the impossibility of social distancing with children under five, and the fact we have high exposure to bodily fluids.

But the most frequently mentioned struggle for teachers in Australia was maintaining quality in pedagogy and curriculum delivery. Teachers are worried the quality of education might be compromised during this uncertain time.

One teacher said:

We are in social repair time. And you know what — no one cares what we are doing in our rooms — just get through ‘til term’s end.

The teachers named student disengagement, uncompleted work and the disparity of access to online materials as the key challenges to quality.

The second most frequent struggle was insufficient time to attend to teaching and learning demands. Many reported working 60% to three times more hours than they were contracted and paid. The sudden shift to online required teachers to self manage production and delivery of online teaching and learning materials, without adequate training and resourcing.

In the longer term, this sudden change in education may lead us to think of innovation in the area. But for now, teachers, schools and students are just trying to survive, and they need all the resources necessary to make it through this year — and beyond.![]()

Louise Phillips, Associate Professor in Education, James Cook University and Melissa Cain, Lecturer in Inclusive Education and Arts Education, Australian Catholic University

This article is republished from The Conversation under a Creative Commons license. Read the original article.

Read LessResilient communities: The case for early response capacity building following natural disasters

MacKillop Family Service Institute’s first discussion paper, Resilient communities: The case for early response capacity building following natural disasters, reviews the existing vulnerabilities of communities impacted by the 2019-2020 summer bushfires and considers the support these communities require to effectively recover and build resilience, recognising the loss, grief and trauma they have experienced has now been compounded by COVID-19.

The bushfires across New South Wales, South Australia, Victoria and southern Queensland were unprecedented. Several of the communities devastated by the fires had also previously been impacted by other recent natural disasters. And now COVID-19 is reshaping the world and directly impacting these same communities by hampering efforts of locals to rebuild their homes, businesses and lives.

The Stormbirds (natural disaster program) and Seasons for Growth evidence-based change and loss programs aim to build the professional capacity of education sector to improve outcomes for children, young people and families. Stormbirds allows children and young people to give voice to their experiences and celebrate how they have managed and how the community has come together in response to an event.

The discussion paper provides an overview of the impact of these events for some communities in NSW and Victoria, providing recommendations for support.

Stormbirds training is available in the following areas:

NSW Southcoast funded by nib foundation & Coordinare: 28th August

Victoria – Alpine area and Gippsland funded by UNICEF & Gippsland PHN: early September

SA – Kangaroo Island and Adelaide Hills funded by the St George Foundation

If your school is in these areas and you would like to participate in the training, please complete this link. Please also complete your details if you would like to discuss additional training in the Stormbirds program. Further Stormbirds information can be found on the Good Grief website.

5 min read

Sally Larsen, University of New England and Callie Little, University of New England

Whether to hold a child back from starting school when they are first eligible is a question faced by many parents in Australia each year.

If you start a child at school too early, there’s a fear they may fall behind. But many working parents may wish to send their child to school as soon as they are eligible. Some data from NSW indicates children from more advantaged areas are held back more often than their less advantaged peers. And boys are more likely to be held back than girls.

We compared the NAPLAN reading and numeracy results of children who were held back with those who were sent to school when first eligible. Our results — published in the journal Child Development — suggest delayed school entry does not have a large or lasting influence on basic reading and maths skills in middle primary and lower secondary school.

Delaying school entry across Australia

School entry cut-off dates vary by state. In most Australian states children born between January and the cut-off date are allowed to begin school aged four. Or they can be held back for an extra year and begin school at five years old. In most states, students must be enrolled in school by the time they turn six.

The exceptions are Tasmania, where children must turn five by January 1 before entering school and Western Australia, where state education policy actively discourages holding children back. In WA parents must gain permission from education authorities before they can hold back their child from starting school.

In NSW, Victoria and Queensland, parents can make the decision to hold their child back without formal permission from school principals or state education departments.

The percentage of children held back from starting school when first eligible varies considerably across the country.

Holding some children back from school and sending others when first eligible means the age range in classrooms can be as much as 19 months between the youngest and oldest students.

Some international research shows children who are held back do better in academic tests in the early years of primary school — up to about Grade 3. There is also some evidence to show students held back are less likely to be rated as developmentally vulnerable by their teachers.

Read more: Which families delay sending their child to school, and why? We crunched the numbers

But other research shows no long-term academic advantage of being held back. Some Australian research found students who were younger in their grade cohorts were more motivated and engaged in early high school than their older peers.

In all, prior research has provided mixed evidence. Little largescale research has been conducted in Australia exploring the associations between delayed entry and academic outcomes in later grades. This is a gap we wanted to fill.

Our research on delayed entry

We were interested in finding out whether children who were held back from starting school performed better in NAPLAN tests in Years 3, 5, 7 and 9. NAPLAN tests can tell us broadly how well children are going in reading and maths.

We compared the scores of 2,823 children in the reading and numeracy sections of NAPLAN tests at each grade.

We found students in Year 3 received slightly higher results in NAPLAN if they were held back, compared to their peers who were not. But this slight advantage reduced at Years 5 and 7. By Year 9 students who were held back did no better on NAPLAN tests than those sent when first eligible.

When we took into account individual differences in students’ ability to focus attention, there was no difference in achievement between students who were held back and those sent on time in any grade level.

Read more: Don't blame the teacher: student results are (mostly) out of their hands

Even differences in age exceeding 12 months appear to make little difference to NAPLAN achievement later in school. The results also indicate individual differences in ability to focus may matter more for NAPLAN achievement than being held back a year.

What we didn’t look at

This research can tell us about averages but it can’t tell us about individual circumstances that might warrant holding a child back from school. Early childhood teachers may recommend children with developmental delays or notable difficulty with language or behaviour be held back for an additional year.

Parents may also take into account the social skills of children when making decisions about delayed entry. We did not investigate social or behavioural outcomes in this research so we cannot draw conclusions about the association between delayed school entry and these important skills.

But this research suggests that despite some initial advantages for children who are held back, all children - regardless of age at school entry - make consistent progress in their reading and numeracy skills from Grade 3 to Grade 9. And any initial advantages for delayed children arenegligible by the middle of secondary school.

Sally Larsen, PhD candidate, Education & Psychology, University of New England and Callie Little, Postdoctoral research fellow, University of New England

This article is republished from The Conversation under a Creative Commons license. Read the original article.