Filter Content

- Australian Catholic Super

- Camp Australia

- Michael Carr-Gregg discusses the phone ban - what do you think?

- Teachers Health

- The Importance of Self-Care for Administrators

- School Shades

- Better pay and more challenge: here's how to get our top students to become teachers

- GOOD GRIEF

- Teeth on Wheels

- Students with disability have a right to inclusive education: Reviewing the Melbourne Declaration

- WOODS Furniture

- MSP

- Human skills needed in an unpredictable world!

- ParentTV

- One in 10 Aussie kids care for someone with a disability or drug dependence – they need help at school

- Switch Recruitment

- SPOTLIGHT - WESTERN AUSTRALIA

- Hear and Learn

- Education Matters Magazine Subscription

- Programmed Property Maintenance

- The Imagination Declaration: young Indigenous Australians want to be heard – but will we listen?

- PETAA

- Pixevety

- The Breakthrough Coach

- SZapp...Have you downloaded yours yet?

- ACPPA Alumni

- Just a Thought!

The Importance of Self-Care for Administrators

5 min read

School leaders benefit from setting up and maintaining a system of support to help them meet the many challenges of the job.

“The moment you want to retreat is the exact moment you have to reach in.”

As an administrator, I use this mantra when the work feels too difficult or the feedback seems too tough, to remind myself that the challenge is also a moment of opportunity.

For some school leaders, it is counterintuitive to think that they might need to ask for help. But in order to thrive, it’s vital that school leaders reach out and create pathways for support. How do they seek support?

Find Connection

Who are your supporters? Who can you trust to discuss challenges and solicit advice? Cultivating these relationships is important for any school leader. Online collaboration may be useful, and finding the right platform is critical. Voxer, a walkie-talkie app, allows me to ask questions of other educators and respond to their inquiries. I use Twitter and Facebook groups to find other leaders who are experiencing challenges similar to mine.

Don’t forget about opportunities for support in real life. Connecting with colleagues in your district or surrounding communities offers you an opportunity to discuss your situations and scenarios with someone who understands your context. About three years ago, I was struggling to figure out how to get it all done at school and at home. I contacted two other principals within my district whom I had admired throughout my career, to find out how they balanced school leadership and parenting. What started as a dinner to help me with immediate problems became a monthly event where we share our experiences.

Read to Learn

Reading up on best practices and tips from others can help administrators gain perspective.

- Making a commitment to a regular practice of reading gives a fresh viewpoint on ways to make your school better.

- Share your resources with your staff. In the weekly newsletter I send to my staff, I include a quote from what I’m reading. This has opened a door for staff to have conversations about what I posted or offer other reading suggestions of their own.

- Share with your students. Each week I post a #BookSnap—a short quote or image from a book that is usually shared on Twitter or Snapchat—outside my office. It’s exciting to see students’ reactions—to my social media skills as well as to the book.

Build Routines

Work stress often means stress outside of work as well. Recalibrating throughout the year is critical to stay focused and connected.

When was the last time you exercised? Read a book for fun? Went to the movies? Spent time with a friend? If the answers are distant memories, you may be in need of a self-care tune-up.

Build time in your calendar to commit to your passions. Attendance at school events, field trips, and board meetings may pull us out of balance, so it’s important to be intentional about our routines. Make time for exercise and family interactions. Good health is essential to the ability to do our job and must be a priority.

Reflect and Reframe

In those dark moments of doubt where you question your choice to become a school leader, step outside of your circumstances to see the bigger picture. Reframing a challenge is a useful way to gain perspective.

Each morning, I use daily journaling. On one side of a page, I write, “Grateful For,” and list my items of gratitude. On the other side I write, “Looking Forward To,” and reframe items I might otherwise avoid. For example, instead of writing, “yet another parent conference,” I write, “looking forward to creating a stronger connection with a parent through relationship-building at parent conference.” This daily reflection takes two to three minutes to complete and creates a sense of purpose for the day and gratitude for what can be accomplished.

Be Mindful

As the adage goes, “Be mindful, even when your mind is full.” Incorporate simple mindful strategies into your day for shelter from the day-to-day stress.

Take a breath. The next time a stress-inducing email shows up in your inbox, take a physical inventory. Are your teeth clenched? Did you hold your breath? Are your shoulders tight? Making sure our physical response to stress doesn’t impact our emotional response to a situation is critical.

If you’ve been in a meeting or working on a project for some time, take a moment to stand up, take a deep breath, and stretch. Adding a quick walk for fresh air gives you new ideas for the challenges ahead.

At the moment we feel most challenged as administrators, it’s important to pause and remember the value of caring for ourselves as well as our students, staff, and schools.

Edutopia

David Whetton

Phone: 0418283876

Email: david@schoolshades.com.au

Better pay and more challenge: here's how to get our top students to become teachers

5 min read

Peter Goss, Grattan Institute and Julie Sonnemann, Grattan Institute

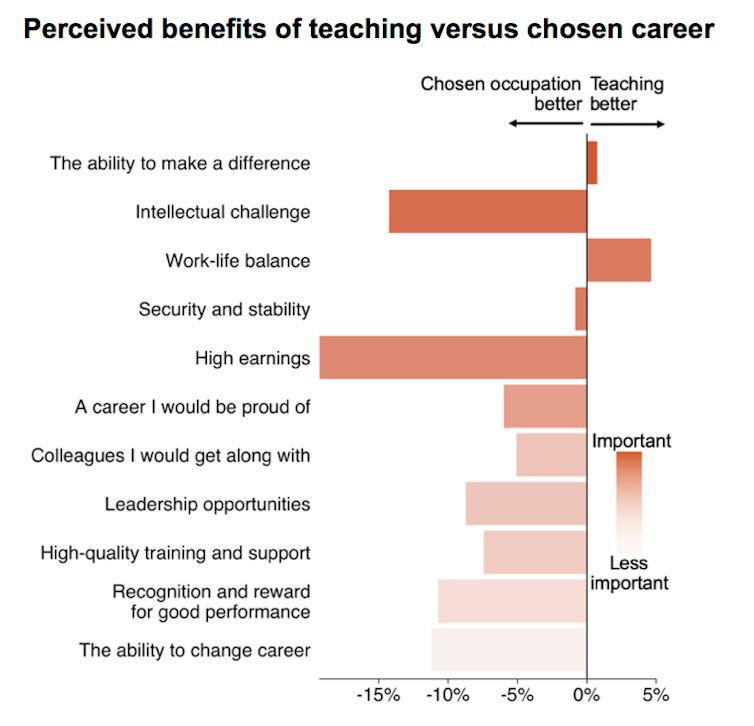

Australia’s young high achievers are turning their backs on teaching. They want to make a difference in their careers, and they are interested in teaching, but when it comes to the crunch they choose professions with better pay and more challenge.

This is not just a cultural problem – governments can and should do more to make teaching an attractive career for our best and brightest. If they don’t, we’ll feel it for generations to come.

A Grattan Institute survey of 950 young high achievers Australia-wide shows what might change their minds. In our new report, Attracting high achievers to teaching, we propose a reform package that would transform the teaching workforce within a decade.

Read more: Here's how to support quality teaching, with the evidence to back it

Attracting high achievers

More high achievers in teaching would mean more student learning. International evidence shows teachers who are good learners themselves do a better a job in the classroom. One New York City initiative cut the achievement gap between the poorest and richest schools by a quarter simply by encouraging high achievers to become teachers in poorer schools.

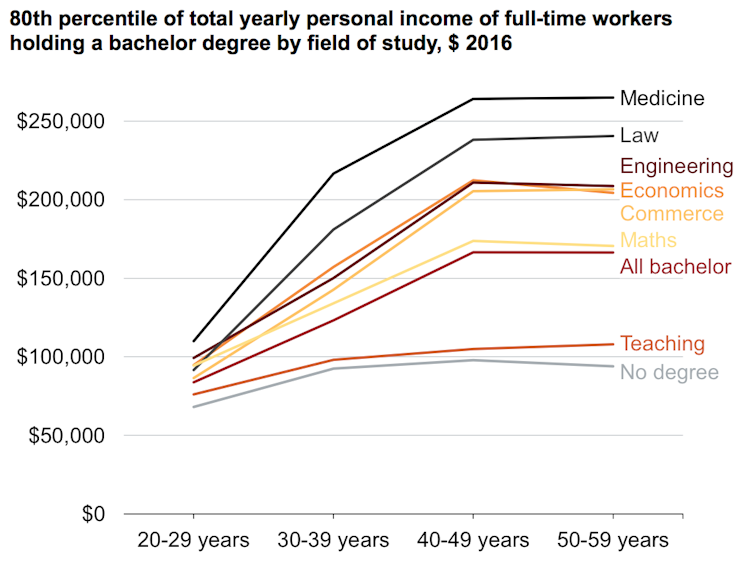

But in Australia, demand from high achievers for teaching has steadily declined over the past 40 years. As top-end salaries for teachers became less competitive with other professions, fewer high achievers chose to teach.

Over the past decade, high-achiever enrolments in teaching courses fell by a third – more than for any other undergraduate field of study.

Today, only 3% of young high achievers choose teaching in their undergraduate studies, compared with 19% for science and 9% for engineering.

Better pay and more challenge

Our survey of young high achievers (aged 18-25 and with an ATAR of 80 or higher) found the best and brightest would take up teaching if it offered better top-end pay and greater career challenge.

This does not mean young people today are not altruistic. In fact, all higher achievers in our survey said they wanted to make a difference. But they thought they could do so in any number of better-paid careers.

High achievers’ big worry was that they would get stuck in the one classroom, doing the same thing over and over again. They knew teaching is a tough job, but they wanted greater intellectual challenge and “the ability to move forward”. As one respondent told us:

It feels like teachers don’t have a clearly defined career progression path.

High achievers also know that teaching falls short on pay. They estimated that by the time they reached the top of their chosen career, they would be earning A$142,000 a year. That’s a very achievable goal in fields like law, engineering, and commerce. But for teachers, that sort of salary is only a very remote possibility.

How to reform the teaching workforce

We propose a $1.6 billion reform package for government schools to double the number of high achievers choosing teaching within a decade. The reform package would lift the average ATAR of teaching graduates from 74 to 85, and when fully implemented would give the typical Australian student an extra six to 12 months of learning by Year 9.

The package has three key components.

First, offer $10,000-a-year cash-in-hand scholarships to high achievers to study teaching, a fast and cheap reform.

Second, make career pathways more challenging, by offering new roles with much higher pay and significantly more responsibilities. About 5-to-8% of teachers would become Instructional Specialists, responsible for helping all other teachers in their school to improve, and paid around $140,000 each year – $40,000 more than the highest standard pay rate for teachers.

About 0.5% of teachers would become Master Teachers, responsible for improving the quality of teaching in their region, and paid around $180,000 a year – $80,000 more than the highest standard teacher pay.

Third, run a $20 million-a-year marketing campaign, similar to the Australian Defence Force recruitment campaigns, to promote the new package and re-position teaching as a challenging and well-paid career option for high achievers.

The reforms package will help current teachers too. All teachers benefit if there are better opportunities for career progression, higher pay and new dedicated roles that help teachers develop and improve.

The package would costs $620 per government school student per year, or $1.6 billion across the country. It’s not cheap, but it is affordable – and ultimately it would pay for itself many times over in improved educational outcomes for future generations.

Read more: Expert panel: what makes a good teacher ![]()

Peter Goss, School Education Program Director, Grattan Institute and Julie Sonnemann, Fellow, Grattan Institute

This article is republished from The Conversation under a Creative Commons license. Read the original article.

MacKillop Family Services and its Education and Grief and Loss programs are hosting a national two-day conference as part of its commitment to support children, young people and families to heal from adversity.

There is a strong evidence base about the impact of grief, loss and trauma on children and young people. Loss and trauma can come in many forms, from the death of a loved one, to family breakdown, or separation from family. It is critically important for professionals working with children and young people to understand the impact of trauma, and to develop the skills to create a safe environment to support them to recover.

National and international experts in helping children deal with loss and trauma will come together for the Lead the Way Towards Wellbeing conference in Sydney on 31 October and 1 November 2019. Through presentations and workshops, they will share their experience in innovative early intervention programs, whole school approaches and the latest research regarding the impacts of trauma, loss and grief on students’ wellbeing and learning.

Prof Anne Graham AO, teacher, founding Director of the Centre for Children and Young People at Southern Cross University and author of the well-known Seasons for Growth loss and grief education program will join the conference to share research outcomes linking student wellbeing and participation rights, including opportunities for children and young people to have a voice in decision-making that impacts on their lives. In addition, Anne will lead an interactive workshop focusing on what it means to authentically accompany children and young people as they make sense of the events and experiences that shape their lives.

Keynote speaker Assoc Prof Judith Murray, Director of the Master of Counselling and Psychology Programs at The University of Queensland, will explore the theory and lived experience of grief and trauma, guiding conference participants to make the connections between the ‘mind and body’, including the power of story to ensure we attend to the ‘whole’ experience of children and young people.

Brendan Murray, Director of Article 26, and founding Executive Principal of Parkville College, will present the innovative ReLATE Model, demonstrating how the capacity of school leaders and a core team of staff can be supported to lead and sustain trauma-responsive school change, guided by experienced education consultants.

In her keynote address, Rosie Batty OA will share the impact of Family Violence and the experiences of loss and grief, a major issue in Australia irrespective of age, culture, sexual identity, ability, ethnicity, religion or socioeconomic status.

Education workshops will address loss and grief, exclusion, conflict, emotional and behavioural difficulties and mental health issues with evidence-based strategies that can be integrated into classroom management, wellbeing and pastoral care practices in your school. These evidence-based strategies support students to heal and re-engage with learning while supporting staff wellbeing and sustainable change.

Particularly relevant for principals, teachers and wellbeing personnel who are eager to lead the way towards better wellbeing and learning outcomes in their schools, the conference will provide an opportunity to explore and network with colleagues and the speakers on emerging school-based issues. Professionals trained to deliver the Seasons for Growth Program will have the opportunity to build on their existing knowledge and network with Companions and Trainers from Australia and overseas.

The conference program has been approved by TQI and has been submitted to NESA for accreditation of professional development hours and meets the requirements for Special Needs of Teacher Registration Boards in other states.

Lead the Way Towards Wellbeing takes place on Thursday 31 October and Friday 1 November 2019. It will be held at Waterview, Bicentennial Park, Sydney Olympic Park.

Find out more about the conference and registration details by clicking the banner above.

Students with disability have a right to inclusive education: Reviewing the Melbourne Declaration

Students with disability were not identified as an explicit priority within the Melbourne Declaration, a statement that was agreed back in 2008 by all Education Ministers in Australia. It stated that the main goal for education in Australia should be equity and excellence for all young Australians and outlined a commitment to action.

Now the declaration is being reviewed and we believe this presents an opportunity to address a critical gap in the original Declaration, which made no reference to inclusive education for students with disability, despite being published in the same year that Australia ratified the United Nations Convention on the Rights of Persons with Disabilities (CRPD) and despite explicitly mentioning other equity groups.

The CRPD imposed legally binding obligations on State Parties including, through Article 24, to ensure an inclusive education system at all levels. This Review of the Melbourne Declaration provides the opportunity to emphasise the important role that inclusive education provides in combating discrimination to create a fairer and more cohesive society in which people with disability are active contributing members.

Omission of students with disability from the Melbourne Declaration

Many of the initiatives that resulted from the Melbourne Declaration perpetuated disadvantage for students with disability because they were not mentioned explicitly in the declaration. For example, by not naming students with disability as a priority equity group, there was no requirement to report disaggregated data for these students in NAPLAN or My School as there was for socioeconomic status and Indigeneity. As a consequence, students with disability have been viewed as a liability by many schools, resulting in increased gatekeeping. Troubling statistics regarding low school completion rates, poor engagement in further education, and high post-school unemployment also show that schooling outcomes for Australians with disability have not improved during the period of the Declaration. This Review presents an important opportunity to ensure that improving the equity and quality of education for students with disability is named as a key priority.

The right to an inclusive education

In 2016, the United Nations published General Comment No. 4 (GC4) to provide guidance on the right to inclusive education. GC4 defined inclusive education, making it clear it is distinct from (i) segregation, which is when students with disability are educated in separate schools and classes, and (ii) integration, which is when students with disability are enrolled in unreconstructed mainstream schools with the onus placed on the student to adjust to such environments. GC4 also explicitly specified the steps State Parties must undertake to realise the right to inclusive education. GC4 and General Comment No. 6 on equality and non-discrimination (GC6), which was published by the UN last year, state that the segregation of students with disability in education is a form of discrimination and a contravention of the United Nations Convention on the Rights of Persons with Disabilities. The UN Committee is reviewing Australia’s commitment and progress against the CRPD in September 2019. A new Declaration that reflects Australia’s international legal obligations under the United Nations Convention on the Rights of Persons with Disabilities would help demonstrate genuine commitment and intent, as well as provide a guiding framework to support realisation of the right to inclusive education across sectors nationally.

Proposed additions to the next Declaration

As members of AARE’s Inclusive Education Special Interest Group, and All Means All: The Australian Alliance for Inclusive Education, we have called upon the Federal Government to consider a range of important additions to the next Declaration.

First, we believe that the Declaration must include a commitment towards inclusive education at all levels of education. Any definition of inclusive education must be consistent with the CRPD. This would promote a nationally consistent understanding of inclusive education.

Second, the Melbourne Declaration stated that “Australian governments and all school sectors must provide all students with access to high-quality schooling that is free from discrimination based on … disability”. The lack of an explicit reference to inclusive education in the Melbourne Declaration leaves both the quality and model open to interpretation. Replacing “high-quality schooling” with“high-quality inclusive education” would align the new Declaration with the National Disability Strategy (2010 – 2020).

The new Declaration should also emphasise the importance of active participation, consultation and involvement of children and their representatives in needs determination and education provision. This would ensure Australia meets its obligations enshrined in the Convention on the Rights of the Child (1989), the Disability Standards for Education 2005, as well as elaborated in CRC General Comment 9 (2006) on the rights of children with disabilities, CRC General Comment 12 (2009) on the right of the child to be heard, and the aforementioned GC4 and GC6.

Third, the Melbourne Declaration stated that: “Australian governments and all school sectors must … reduce the effect of other sources of disadvantage, such as disability, homelessness, refugee status and remoteness”. However, the Declaration gave no indication as to how this might be achieved, and made no acknowledgement of the societal barriers that create and perpetuate the disadvantage that constitutes disability. In the next Declaration, we recommended the following revised statement,

Australian governments and all school sectors must ensure that structural, physical, attitudinal and cultural barriers to learning, participation and achievement are removed, that students are actively involved in decisions made about their education, and effective teaching and leadership practices are implemented, to support all students in making progress at school regardless of their personal characteristics.

Fourth, the Melbourne Declaration stated that: “Australian governments and all school sectors must … promote personalised learning that aims to fulfil the diverse capabilities of each young Australian”. This terminology is not consistent with the terminology being used in recent cross-government initiatives, such as the National School Improvement Tool or the Nationally Consistent Collection of Data on Students with Disability. In the next Declaration, we recommend the phrase “personalised learning” is replaced by “quality differentiated teaching practice”, “Universal Design for Learning” and “reasonable adjustments”.

Our vision for Australian education

The next national aspirational declaration on Australian education should put forward a view of educational purpose that is ambitious for, and inclusive of, all Australian students. It should provide guidance to ensure that purpose and vision is achieved for all students, in ethical and inclusive ways. It should require appropriate support to enable the educational growth of all students and embrace student diversity as inherently normal and economically, culturally and socially beneficial. It should cover all levels of education -- early childhood, school, vocational and higher education -- and express broad principles expected of each.

The Declaration should motivate and inspire educators, and school and system leaders, as well as gather all stakeholders around a common goal. It should be consistent with the Australian government’s obligations under the United Nations Convention on the Rights of Persons with Disabilities with a clear progression to end segregated education and exclusionary practices. The removal of systemic pressures that might inhibit the progress of inclusion has education, employment and lifelong benefits for all.

Dr Shiralee Poed is a senior lecturer in learning intervention at the Melbourne Graduate School of Education within the University of Melbourne. Shiralee is also the co-chair of the Association for Positive Behaviour Support Australia, member of the AARE Inclusive Education SIG, and member of the All Means All Academic Advisory Panel.

Professor Linda Graham leads the Student Engagement, Learning and Behaviour (SELB) Research Group in the Faculty of Education, Queensland University of Technology. Linda is also the co-convenor of the AARE Inclusive Education SIG, and board member of All Means All – Australian Alliance for Inclusive Education and Chair of the All Means All Academic Advisory Panel.

Cátia Malaquias is a lawyer, an award winning human rights and inclusion advocate and a co-founder and an Advisor of All Means All. Catia is also the founder and director of Starting With Julius, a board member of the Attitude Foundation and Down Syndrome Australia, and a co-founder of the Global Alliance for Disability in Media.

Dr Kate de Bruin is a lecturer in inclusion and disability in the Faculty of Education at Monash University. Kate is also a co-convenor of the AARE Inclusive Education SIG, and member of the All Means All Academic Advisory Panel.

Dr Ilektra Spandagou is a senior lecturer in inclusive education at the University of Sydney. Ilektra is also a member of the AARE Inclusive Education SIG, and member of the All Means All Academic Advisory Panel.

Dr Jenna Gillett-Swan is a senior lecturer and researcher in the Faculty of Education at QUT. Jenna is also a member of the AARE Inclusive Education SIG, and member of the All Means All Academic Advisory Panel.

Emily Cukalevski is a lawyer and disability rights advocate. Emily is also an advisor for All Means All.

Dr Peter Walker is a lecturer in inclusive education at Flinders University. Peter is also a member of the All Means All Academic Advisory Panel.

Marijne Medhurst is a senior research assistant in the School of Early Childhood and Inclusive Education within the Faculty of Education at Queensland University of Technology (QUT).

Haley Tancredi is a research assistant and sessional academic in the School of Early Childhood and Inclusive Education within the Faculty of Education at QUT, and a certified practising speech pathologist. Haley is also a co-convenor of the AARE Inclusive Education SIG.

Dr Kathy Cologon is a senior lecturer in inclusive education at the Department of Educational Studies, Macquarie University. Kathy is also a member of the All Means All Academic Advisory Panel.

This article was originally published on EduResearch Matters. Read the original article.

10 min read

Myra Hamilton, UNSW and Gerry Redmond, Flinders University

Children who care for a family member with a disability, mental illness or dependence on alcohol or other drugs are less likely to complete, or do well in, secondary school compared with young people without caring responsibilities.

Our study, published in the journal Child Indicators Research, compared the levels of school engagement among children who identified as carers with children who didn’t shoulder such responsibilities.

We measured levels of school engagement by asking how often children felt positive emotions, such as being happy and safe, towards school.

In a national school-based survey of 5,220 Australian children aged 8-14, more than 450 respondents (9% of the sample) indicated they were looking after a family member with a disability or another serious health issue.

More than half of these young carers had responsibilities for a family member with a mental illness or dependence on alcohol or other drugs.

Overall, we found children who cared for a person with a mental illness or one using alcohol or other drugs had significantly lower engagement at school than children without caring responsibilities.

Studies show children who are more engaged at school are more likely to stay in school longer, with better outcomes for employment and earnings.

The challenges facing young carers will continue without improved support in schools and broader policy and community services, as well as personalised intervention programs.

Who are young carers?

Young carers are children and young people who provide substantial unpaid care to a family member with a disability, chronic or mental illness, dependence on alcohol or other drugs, or frailty due to old age.

The people they care for include parents, siblings, grandparents, extended family or friends. Most young people take care of a parent or sibling.

About 5-10% of Australian young people aged under 26 (that’s between about 150,000 and 300,000) are carers. There is some suggestion the figure could be even higher.

They help their family members with a range of activities beyond those typical of a person that age.

This includes helping with personal care such as showering and going to the toilet, administering medication, liaising with doctors and services, overseeing household administration and finances or providing emotional support.

Previous research has shown young carers’ responsibilities negatively affect their educational outcomes. For instance, young carers are more than one year behind their peers in literacy and numeracy.

They are also less likely to complete secondary school and aspire to university after leaving school.

Why are young carers less engaged in school?

We compared the levels of young carers’ school engagement with those of their peers without care responsibilities.

We measured emotional engagement in school by asking young people whether they felt happy and safe at school, and whether they enjoyed going to school and learning. We also measured their behavioural engagement by asking about how often they did homework.

Young carers of a person with a mental illness or drug or alcohol dependence were significantly less likely than young people who were not carers to report feeling happy and safe at school and enjoying school. They were also significantly less likely to do homework daily compared with students who weren’t carers.

Our results showed little difference in the school engagement of young people who took care of a person with a physical or intellectual disability compared with young people who were not carers. But previous research suggests this group of young carers also faces considerable challenges at school.

Past research shows the responsibilities of a young person caring for someone with a mental illness or alcohol or drug dependence are often unpredictable. They manage crises, as well as monitoring the person’s well-being and medication use, which may heighten young carers’ levels of worry while at school.

Research also suggests many young carers of a person with a mental illness or drug or alcohol dependence keep their caring responsibilities a secret from their peers and school professionals. This is often to protect themselves and their families from bullying and for fear of intervention by child protection services.

The strain of concealment is likely to affect the carers’ own mental health and create a barrier to them seeking support. This may, in turn, affect the quality of their school experience.

We also found poor engagement in school of young carers of a person with a mental illness or using alcohol or other drugs was amplified by other indicators of marginalisation. These included whether the young carer themselves had a disability, was from a lower socioeconomic background or identified as Indigenous.

This suggests even stronger barriers to school engagement among young carers who experience multiple forms of marginalisation.

How can we help young carers?

Carer organisations and governments provide resources to schools, such as teacher toolkits, that raise awareness about young carers’ needs among staff and students and support their continued education.

The federal government has also announced new packages – available from later in 2019 – to support carers with education and employment. But only about 5,000 packages will be provided and only a small share of these will be earmarked for young carers.

Likewise, a Young Carer Bursary of A$3,000 was introduced in 2014 to support young carers to attend school – but only 1,000 of these are available in 2019.

Read more: Looking after loved ones with mental illness puts carers at risk themselves. They need more support

While current policies may be making a positive difference for some carers, the results in this study show there are more young carers than support services available for them.

More needs to be done for the large number of young carers who are not as engaged in school as their peers. This includes high-quality, affordable and accessible services for their family members requiring care.A personalised approach that includes the entire family and greater awareness and understanding among teachers and students of mental illness and drug or alcoholusecould help make the school environment more welcoming for young carers.![]()

Myra Hamilton, Senior Research Fellow in Social Policy, UNSW and Gerry Redmond, Professor, College of Business, Government & Law, Flinders University

This article is republished from The Conversation under a Creative Commons license. Read the original article.

CPPAWA Conference 2019

The annual CPPAWA Conference was held at the Joondalup Resort and Country Club from Tuesday 30 July to Thursday 1 August. It provided us the perfect opportunity to have time together to share new learnings as well as participate in networking and wellbeing opportunities. To extend the learning opportunities for all leadership teams, the Assistant Principals were invited to the first day of the conference as we believe in sharing these professional learning opportunities so as to enable change within schools where the Principal is not the sole driver.

This year’s theme was “Setting the Agenda” and we had two world class presenters. The first Keynote Speaker was Dr Tracey Tokuhama-Espinosa, who gave an outstanding presentation on the Neuroscience of Learning and designing educational experiences. Tracey runs an online course at Harvard University each year entitled, “The Neuroscience of Learning: An Introduction to Mind, Brain, Health and Education”. Some points that Tracy shared on what scientists know about the brain and learning are:

- The person who does the work is the person who does the learning

- The brain is rather social, most of us learn in groups

- We know ourselves better by knowing others

- All learning occurs through your senses

- There is no learning without emotions – a child who is anxious, stressed and/or depressed will not learn

Her session on how the brain works and long held myths/beliefs was very interesting.

- Human brains are as unique as human faces – TRUE (how does this knowledge impact our teaching?)

- All brains are equally prepared for all tasks – FALSE (differentiation is the key)

- The brain changes constantly with experience – TRUE (are we providing enough opportunity/time for rehearsal for all students in class, even those with little prior knowledge?)

- The brain is highly plastic – TRUE (children who believed their intelligence could be developed outperformed those who believed their intelligence was fixed)

Further information on Tracey’s work can be found on www.thelearningsciences.com

PICTURE: Sitting down: (Tracy Arnold (Executive Officer of CPPA), CPPA Executive Members – Sandro Coniglio, Mark Powell (President), Art Lombardi. Back Row: Laurie Bechelli (Conference Organiser), Dr Tracey Tokuhama-Espinosa.

Wednesday 31 July commenced with a beautiful Mass celebrated by Bishop Don Sproxton. Following the service, Bishop Don discussed some of the big issues currently facing the Church, and what he believed was the best way forward. The rest of the day was spent discussing CPPA issues, networking and taking part in wellbeing activities.

On Thursday 1 August, Dave Faulkner and Aaron Tait from Education Changemakers presented three lively, engaging and challenging sessions entitled “MBA in a Day” which looked at the future of education, dealing with change and working with challenging members of staff. If you would like to learn more about Education Changemakers, please go to their website www.educationchangemakers.com

‘The illiterate of the 21st Century will not be those who cannot read and write, but those who cannot learn, unlearn and relearn’. Alvin Toffler (He predicted the rise of personal computers, the internet, cable TV and cloning).

The CPPA 2019 Conference challenged our thinking and exposed us to the latest research on learning, the brain and how to go about having the courage to initiate and deliver change in our schools. These days where we come together as a body of professionals assists us to collaborate and learn whilst building support networks to help us through changing and challenging times.

Laurie Bechelli

Principal – Mary MacKillop Catholic Community Primary School, Ballajurra

CPPA Executive Member (Conference Organiser)

Education Matters Magazine Subscription

A free subscription offer for both the print edition of Education Matters and e-newsletter for all ACPPA members?

Click the special link below.

ACPPA members can then sign up by filling in the relevant details. There is a separate section for the Primary and Secondary magazine, enabling you to sign up to one of both magazines.

ACPPA President Brad Gaynor is featured in the latest issue with an opinion piece. Have a look!

The Imagination Declaration: young Indigenous Australians want to be heard – but will we listen?

10 min read

Marnee Shay, The University of Queensland; Annette Woods, Queensland University of Technology, and Grace Sarra, Queensland University of Technology

When you think of an Aboriginal or Torres Strait Islander kid, or in fact any kid, imagine what’s possible. Don’t define us through the lens of disadvantage […] Expect the best of us. – Excerpt from the Imagination Declaration, August 2019.

A group of school students from across Australia have just shown what real leadership on Indigenous issues looks like.

At last week’s national Garma Festival, 65 Indigenous and non-Indigenous students from years six to 12 came together for a Youth Forum and wrote their own follow up to 2017’s Uluru Statement from the Heart. They called it the Imagination Declaration. It’s a challenge to the prime minister and education ministers to involve young people – and Indigenous Australians in particular – in making policy about their future.

With 60,000 years of genius and imagination in our hearts and minds, we can be one of the groups of people that transform the future of life on Earth, for the good of us all.

We can design the solutions that lift islands up in the face of rising seas, we can work on creative agricultural solutions that are in sync with our natural habitat, we can re-engineer schooling, we can invent new jobs and technologies, and we can unite around kindness.

We are not the problem, we are the solution.

Young people under 25 years make up more than half of the Indigenous population, even more than the one-third proportion of non-Indigenous Australians the same age. Yet we rarely hear the perspectives of the future leaders and custodians of the oldest living culture in the world.

That was true even of last week’s Imagination Declaration, which was briefly reported by just one media outlet, NITV.

But there’s a good chance you’ll hear more about “the Imagination agenda for our classrooms” at your local school, childcare centre or university in coming months, as Indigenous mentoring organisation AIME plans to share the declaration nationally for other Australians to sign if they support the students’ goals.

Read more: How a robot called Pink helped teach school children an Aboriginal language

The students invite the prime minister and education ministers to meet them and listen to their ideas. Cynics might dismiss that as too idealistic – but as education researchers, we’ve seen the genuine difference listening to and “expecting the best” of young people can make.

Lessons from Queensland and WA high schools

We’ve spent the past three years in six urban, regional and remote communities across Queensland and Western Australia, working with more than 100 young people in a diverse range of high schools.

One of the reasons for doing the “Our Stories, Our Way” project was that while you can find hundreds of studies about Indigenous young people – usually with a negative, “closing the gap” focus – when we searched for health or education research on identity from recent decades, we found just 14 studies that specifically included the voices of Indigenous Australians under 25.

We helped create spaces where Indigenous young people had a rare chance to share their hopes with their communities, schools and each other, ranging from “I want to go to uni and study physiotherapy” to:

No matter what happens we should all be proud of whatever culture we are, no matter what culture/colour. We are all people, our skin colour shouldn’t matter

Our project focused on identity, health and well-being. Young people were given resources to make a creative piece that reflects their identities, in their words.

Some chose to create clothes and posters with art representing their stories, with messages such as “our pride, our culture” and “strive with pride”. In two urban Brisbane schools, young people wrote and recorded their own rap songs, filled with powerful lyrics such as:

Listen to the medley, black and deadly

Searching for acceptance, we must be respected

You can say what you want friend or foe

I feel good in my skin wherever I go

In contrast with negative representations of Indigenous young people, the young people in our project spoke about their values, such as pride, respect for Elders, succeeding, family and being a collective when they explained how they express their identities.

But they also talked about the high levels of racism they experience.

Navigating everyday things, like going to a shop, was a cause of real stress and anxiety for some Indigenous young people. Being followed around, often with the assumption Indigenous young people don’t have money or are going to steal something, is an issue that was reported to us by young people consistently across the project.

Some young people even said they weren’t able to continue attending school due to racism. Asked to explain this, the young people we worked with were frank:

When young black kids, like ourselves, when we feel like we have nothing to do, that’s when we go out and break the law. Then when you’ve got the other good black kids staying in school and going to real good schools … coppers will look at them funny too just because their skin is black. It’s like, you know, not every blackfella is the same.

Lessons for educators from our project

What struck us most was that, in spite of the impacts of negative stereotyping and racism, the young people we worked with showed enormous resilience and ability to understand and navigate complex issues.

Nine local Indigenous researchers worked with our project team. They provided reflections on the impacts they had seen, observing a transformation in young people’s confidence, with a greater “sense of self worth among students … (and) sense of pride and belonging”.

The local researchers also reported that there was more talk within the high schools than before the project about the value of “embedding Indigenous culture in the curriculum” and that “community members were talking about the creative projects by young people and were proud of their achievements”.

One non-Indigenous school leader expressed surprise that even at a high school that had made an effort to embed Indigenous culture into the curriculum, “it was a bit of an eye opener that there is still really a place for the kids for an Indigenous space”.

Read more: Indigenous art centres that sustain remote communities are at risk. The VET sector can help

An Imagination agenda, from childcare to Canberra

The students behind the Imagination Declaration have called on politicians “to establish an imagination agenda for our Indigenous kids and, in fact, for all Australian children”, which stops “looking at us as a problem to fix”.That hope of being included in making solutions – rather than having curricula or policy written without them – was echoed by one of our project’s students: Well if people just listen to us for once … we can make our own job. We can make our own shop, with all the art stuff or Aboriginal kids have grown up in dance and stuff. But the government justneeds tolisten to us.We reckon we’ll make a future. We’ll go all the way.![]()

Marnee Shay, Senior Lecturer and Senior Research Fellow, School of Education and Centre for Policy Futures, The University of Queensland; Annette Woods, Professor in the School of Early Childhood and Inclusive Education, Queensland University of Technology, and Grace Sarra, Associate Professor, Faculty of Education, Queensland University of Technology

This article is republished from The Conversation under a Creative Commons license. Read the original article.

Read LessSZapp...Have you downloaded yours yet?

Would you like ACPPA news and feeds straight to your phone… SZapp is here and can be downloaded on your device. Click the side bar to go to app store.

- Visit the app store for apple or playstore for android and type in SZapp in the search field

- Click icon that looks like this

- Click install

- Once installed Click open

- Click region Australia/Pacific

- Start typing Australian Catholic Primary Principals Assoc.

- Our logo and name should appear

- Registration required

- Register by Clicking and sign in with your email

- Create a password

REMEMBER...ACPPA 'Just the ESSENTIALS' is ONLY available through the APP

Download yours TODAY!

Would you like to get together for a drink or a meal when ACPPA meets in a capital city?

We have already received interest from past members…please email us now!

This photo below was taken at the 2005 Conference in Melbourne.

Great opportunties await for interested past ACPPA Executive to catch up occasionally!

Please contact Executive Officer – paul.colyer@acppa.catholic.edu.au

or Kevin Clancy kclancy@ozemail.com.au for more information.