Filter Content

- Self-care essential for school leaders

- MSP

- SPOTLIGHT - TASMANIA

- ParentTV

- Most Australian teachers feel unprepared to teach students with special needs

- Good Grief

- Australian Catholic Super - The steps to an early retirement

- WOODS Furniture

- School Shades

- The flawed thinking behind a mandatory phonics screening test

- Hear and Learn

- Stop worrying about screen 'time'. It's your child’s screen experience that matters!

- Teachers Health

- Interactive Leadership Profiles Resource from AITSL

- PETAA

- Kindy to Prep Transitions. A new mindset for all Catholic Schools. St Therese's School Bentley Park

- Pixevety

- Teeth on Wheels

- What's the point of education? It's no longer just about getting a job

- Programmed Property Maintenance

- Switch Recruitment

- The Breakthrough Coach

- ACPPA Alumni

- SZapp...Have you downloaded yours yet?

- Just a thought!

Self-care essential for school leaders

5 min read

OPINION: A failure to take care of one’s own wellbeing will quickly blunt a leader’s capacity to do what’s best for others.

A dangerous and flawed perception is doing the rounds of many schoolyards – one that is escalating and rarely challenged.

This perception appears to garner such blind and erroneous acceptance within the education community that, on a daily basis, it blemishes the careers of many school leaders. In the longer term, it prevents them from leading fulfilling professional and personal lives.

This (flawed) perception held by many is that the very best leaders, those who sacrifice their own wellbeing for that of others, create the very best schools.

Many school leaders will tell you that their sense of purpose, commitment and belief in what they do forces them to spend more than 60 hours a week at work, to cope with extraordinary increases in their workload over the past 10 years.

For many, that increased workload has arisen as they grapple with the increased expectations of employers, teachers, parents and even students.

At the same time, school leaders as a group have forged a notorious reputation for failing to embrace proper self-care.

A well-held collective belief among many school leaders is that giving to themselves reduces the time available to give to others. In other words, many school leaders believe that taking time out for exercise or simply to catch up on sleep actually pulls them away from their commitment to helping others.

And it is this belief that has many school leaders teetering on the edge of burnout on a day-to-day basis.

As a condition, the broad characteristics of burnout include feelings of depleted energy levels, increasing disengagement form one’s work, feelings of negativity and cynicism, and reduced professional competency. Hardly ingredients for successful leadership, right?

And despite data from The Australian Principal Occupational Health, Safety and Well-being Survey, which highlights a decline in the wellbeing of principals, many school leaders are yet to jump on the self-care bandwagon.

There are plenty of reasons for school leaders’ apparent failure to embrace their own self-care. Some, for example, are not convinced that burnout is real. After all, it is increasingly being used as a catchall term for a variety of workplace conditions and ailments.

The World Health Organisation has nipped that doubt in the bud, however, by upgrading the definition of ‘burnout’ in its International Disease Classification – the official compendium of diseases – from a ‘state of exhaustion’ to a syndrome resulting from ‘chronic workplace stress’.

Yet some school leaders believe burnout is temporary and can be fixed with a decent holiday. This will help in the short term but do little in the long term if school leaders return to work fresh and recharged, only to then again neglect their daily self-care.

Then there are those who simply believe the cure for burnout is to work smarter, not harder.

Granted, working smarter might free up some time to engage in self-care activities. However, there is a tendency for many school leaders to invest the extra time gleaned from working smarter back into new leadership initiatives, rather than self-care.

But here’s the kicker: school leaders who take care of themselves end up being far better leaders and able to give a lot more than those who hold the view that being a great leader means sacrificing one’s mental health.

If you have travelled on a plane and listened intently to the pre-take off safely announcements, you will find they contain a message for school leaders.

Airlines will advise you to fix your own oxygen mask before you assist others. The easily understood theory is that if you pass out while trying to help others, because you have ‘sacrificed’ yourself in pursuit of prioritising the care of others, you are helping no-one.

The same theory can apply to the school leader. If you relegate the need to take care of yourself to the back of the queue, you won’t be able to serve others in an effective way in the longer term.

So help yourself before you help others by developing an effective professional support network, getting more sleep, taking more time to prepare healthy meals, engaging in regular exercise, taking regular breaks during the day – and perhaps even consider attending a mindfulness workshop, which might help to shelter you from stress.

You will be a better leader for it and take a giant step towards avoiding burnout.

• Professor Gary Martin is chief executive officer at the Australian Institute of Management WA

Teddy bear care teaches valuable skills

PREP students at St Cuthbert’s Catholic School in Lindisfarne put their teddy bears through their paces recently when they were visited by local medical students as part of the University of Tasmania’s (UTAS) Teddy Bear Hospital program.

As part of the program, third-year UTAS medicine students set up a number of different medical experiences for the children including Teddy GP, Teddy surgery, Teddy handwashing, Teddy x-ray, Teddy emergency and Teddy exercise.

The Teddy Bear Hospital initiative was started at UTAS’s School of Medicine in 2013 and is aimed at familiarising young children with hospitals and medical treatment.

“I think it is a great way for the prep students to not only learn more about medicine, but also to help alleviate any fears around things such as going to the GP or the hospital and other medical procedures,” St Cuthbert’s prep teacher Stephanie Cripps said.

“It’s very beneficial for children to have an active interest in their own health and wellbeing.

“Children learn through play and this program was a wonderful hands-on experience for the children to not only learn more about it, but also enjoy getting to know different doctors and other people they may come across in their community.”

Mrs Cripps said the students “absolutely loved” being a part of the school’s first-time participation in the program.

“I asked them what their favourite part was and some of them drew pictures of the different things they did – they were talking about it for a long time afterwards,” she said.

“We might have to make our own Teddy Bear Hospital in our classroom to keep the interest going.”

Third-year medical student Aleksander Wejman said the program was continuously expanding into more Tasmanian schools and had benefits for all students involved.

“The program provides a fun and non-threatening environment for children to learn more about medical encounters, while at the same time helping medical students to develop communication skills in the paediatric setting,” he said.

The Teddy Bear Hospital concept was founded by the International Federation of Medical Students Associations, and the UTAS program is modelled on existing programs run in Australia and overseas.

Marcus Donnelly - St Cuthbert's Catholic School Lindisfarne

Email: marcus.donnelly@catholic.tas.edu.au

Most Australian teachers feel unprepared to teach students with special needs

Jane Jarvis, Flinders University

Fewer than half (38%) of Australian teachers feel prepared to teach students with special needs when they finish their formal training. This is despite 74% having trained to teach in mixed-ability settings as part of their studies.

The latest Teaching and Learning International Survey (TALIS) shows teachers across the OECD felt professional development opportunities were particularly inadequate for teaching students with special needs.

Students with special needs are students for whom a learning need has been formally identified due to cognitive, physical or emotional difficulties.

According to the TALIS report, nearly 30% of teachers in Australia work in classes where at least 10% of students have special needs. The report adds to a body of research suggesting teachers feel unprepared to teach students with special needs in mixed-ability classrooms.

So, how can we better prepare and support teachers for the reality of diverse Australian classrooms? Investing in high-quality pathways to qualification for special education teachers, and expecting every Australian school to employ at least one specialist teacher to support teachers and students, would be a worthwhile place to start.

Better teacher preparation to begin with

Depending on the data source, between 8% and 20% of school-age children have identified disabilities or special educational needs.

Teachers are expected to design learning experiences for students of all abilities and support students with disabilities to participate in learning. This is set out in a national set of professional standards, introduced in 2011, that guide the program content for initial teacher qualifications.

But some critics believe the standards don’t go far enough in relation to teaching students with special needs. Typically, teacher education programs include a semester unit related to teaching students with special needs.

Traditionally, the content was taught “categorically”, meaning lecturers provided introductory information about multiple categories of special need. Contemporary units have shifted away from the categorical model, recognising that teaching in diverse classrooms is more complex than just responding to one individual need at a time.

But while a semester unit can focus on key concepts and practices, these need to be reinforced throughout the program. In fact, given the nature of today’s classrooms, they should be at the heart of the program. Preservice teachers need support to understand evidence-based inclusive practices, address common concerns and misconceptions about inclusion, and apply strategies in practice.

Even with excellent preservice education, a graduating teacher, by definition, is inexperienced. Teaching students with special needs requires skills that develop with time and ongoing support.

Yet, only 37% of early career teachers (those in their first five years of practice) in the survey said they work with an assigned mentor.

Employ qualified specialist teachers

In the TALIS report, almost one in five principals reported the quality of their school’s inclusive education was hindered by a shortage of teachers who were competent in teaching students with special needs.

Not every school is required to employ qualified special education teachers. And the percentage of schools with at least one qualified special education teacher is not known.

One study found even when schools advertise for a special education teacher or coordinator, they often fail to list formal special education qualifications among the selection criteria. And less than one-third explicitly call for special education experience.

Further, there is no nationally recognised pathway to qualification as a special education teacher in Australia. Special education is not a recognised area of specialisation in the standards that guide accreditation of teacher education programs.

This makes it difficult to design specialist undergraduate degrees. At the same time, there is no financial incentive for teachers to do postgraduate qualifications. Under these conditions, it is hard to see how the shortage of qualified specialist teachers will be addressed.

Countries including the US and the UK have developed national, professional standards detailing essential knowledge and skills for special education teachers. These have been formally adopted and guide the content of accredited teacher education programs.

Both countries have clear regulations about qualifications and/or licensure for employment as a special education teacher or coordinator (in the US, these are supported by legislation).

Australia is lagging behind in these key areas, despite calls from researchers and professional associations.

Quality professional development

The TALIS report shows teachers prefer professional development opportunities in which they collaborate with colleagues, such as through peer learning or coaching. Attending one-off workshops remains the most common option for professional development (reported by 93% of teachers), despite the lack of evidence for its effectiveness.

There are promising national efforts to improve induction, mentoring and professional development for teachers.

But the content of professional development also matters. Mentors should understand and be able to support evidence-based inclusive practices. Professional development should also be facilitated by those with expert knowledge. And teachers need ongoing access to information, advice and support in their daily work.

Professional development for inclusive practice can be effective when it:

- actively engages teachers over extended periods

- has clear links to student learning in local contexts

- allows teachers to learn together as part of communities of practice

- is supported by strong school leadership.

Preparing teachers who feel confident to teach students with special needs is essential to having inclusive schools as part of an inclusive society. We shouldn’t underestimate the challenge of teaching for a very broad range of students. Equally, we shouldn’t underestimate the capacity of good teachers to do so, given the right support.![]()

Jane Jarvis, Senior Lecturer in Education, Flinders University

This article is republished from The Conversation under a Creative Commons license. Read the original article.

ACPPA welcomes Good Grief and The Seasons for Growth Program.

Good Grief develops and supports a range of evidence-based loss and grief education programs that help children, young people and adults to understand their experience and attend well to their grief following major loss experiences.

Poll is closed

Australian Catholic Super - The steps to an early retirement

Here are the five things you should consider if you want to retire early.

No matter how much you love your work, chances are that you’re also thinking about the life you want in retirement.

Early retirement is an achievable dream. There are, however, some things you’ll likely need to do to ensure that it’s not just a financially feasible future but a comfortable one as well.

Things to know: When can I access my super?

You can access your super after you reach your preservation age. Depending on when you were born, it’s between ages 55 and 60.

Things to know: How much do I need to retire?

The short (if unsatisfying) answer is that it depends entirely on the kind of life you want to live in retirement. Want to travel a lot? You’ll need more than if you plan to stay close to home.

That said, assuming you own your home, the Association of Superannuation Funds of Australia (ASFA) estimates you will need around $43,000 per year ($61,000 for a couple) to enjoy a comfortable retirement.

Comfortable is a great goal, but if you’re thinking about retiring early you might want more. It’s doable, but it’ll take some planning. Here’s what you should consider to help make it a reality.

- Get a plan

Having goals is a great way to start planning for retirement, but you also need a plan for the small steps along the way. A financial adviser can help you address your debt and expenses while maximising your income and savings.

- Save more, spend less

Retiring early means that you’re going to need more money, sooner. Your focus should be on making the most of every dollar, whether that means paying down debts or putting it into your super. One good place to focus is on paying down the biggest debt most people ever have, your mortgage!

- Take advantage of your super

There are tax benefits to using your superannuation account that may mean your dollar can stretch farther both now and in the future. Pre-tax contributions are taxed at 15% and withdrawals aren’t taxed once you reach age 60.

You can also put after-tax money into super, up to $100,000 with the ability to bring forward up to $300,000 in a single year. This can be a good way to maximise the proceeds from a home sale or inheritance.

The money you put in super is invested and may earn a rate of return significantly higher than a standard savings account.

- Budget for your life in retirement

Knowing how much you’ll need comes down to what you want to do in retirement. What will be your ongoing expenses, like food and utilities? What kind of one-off payments do you foresee, like trips, purchasing a caravan or renovating your kitchen?

Also, factor in future healthcare and aged care costs, things can get more expensive as you age.

- Make your money work for you

How your money is invested can have a significant impact on how much you will have in the future. Keeping your savings in a bank account will keep it accessible, but the return will likely be lower. Having a holistic strategy can be extremely useful in having liquid capital for now without sacrificing growth potential.

You don’t have to go it alone

Having a solid plan for your retirement is the best way to achieve your goals, whatever they may be.

Our financial advisers can help you look at all of your options and find the best path for you.

Let’s have a chat about making your dreams a reality. Call us on 1300 658 776 or speak with your local Australian Catholic Superannuation representative about what we can do for you.

*The information is general in nature and does not take into account your personal objectives, financial circumstances, needs, fees or taxes. You should assess your own financial situation and consult a financial adviser or tax advisor, if required.

David Whetton

Phone: 0418283876

Email: david@schoolshades.com.au

The flawed thinking behind a mandatory phonics screening test

The New South Wales Government recently announced it intends to “trial an optional phonics screening test” for Year One students. This seems to be following a similar pattern to South Australia where the test, developed in the UK, was first trialled in 2017 and is now imposed on all public schools in the state.

The idea of a mandated universal phonics screening test for public schools is opposed by the NSW Teachers Federation, but is strongly advocated by neo-liberal ‘think tanks’, ‘edu-business’ leaders, speech specialists and cognitive psychologists. The controversy surrounding the test began in England, where it has been used since 2012. As in England, advocates of the test in Australia argue it is necessary as an early diagnosis of students’ early reading.

No teacher would dispute the importance of identifying students in need of early reading intervention, nor would they dispute the key role that phonics plays in decoding words. However I strongly believe the efficacy of the test deserves to be scrutinised, before it is rolled-out across our most populous state, and possibly all Australian public schools.

Two questions deserve to be asked about the tests’ educational value. Firstly, is it worthwhile as a universal means of assessing students’ ability in reading, especially as it will be costly to implement? Secondly, does it make sense to assess students’ competence in reading by diagnosing their use of a single decoding strategy?

Perhaps these questions can be answered by interrogating the background to the test in England and by evaluating the extent to which it has been successful.

What is in the test?

The test, which involves two stages, consists of 40 discrete words that the student reads to their teacher. They do so, by firstly identifying the individual letter-sound (grapho-phonic) correspondences, which they then blend (synthsise) in order to read the whole word. So, in fact what is specifically being tested is a synthetic phonic approach to reading, not a phonic approach per se. It could even be argued that calling the test a ‘phonics’ check is a misnomer since analytic phonics is not included.

Students pass the test by correctly synthesising the letter blends in thirty-two of the forty words. In order to preserve fidelity to the strategy and to ensure students do not rely on word recognition skills, the test includes 20 pseudo words. In the version used in England, the first 12 words are nonsense words.

The back ground to the phonics screening check in England.

We can trace the origins of the phonics screening check in England to two influential sources: ‘The Clackmannanshire Study’ and the ‘Rose Report’. In his 2006 report on early reading, Sir Jim Rose, drew heavily on a comparative study conducted by Rhona Johnston and Joyce Watson, in the small Scottish county of Clackmannanshire. After comparing achievements in reading of three groups of students taught using different phonic methods, the two researchers concluded that the group taught by means of synthetic phonics achieved significantly better results than either of two other groups. These other groups were taught by means of analytic phonics and a mixed methods approach. Although the study received little traction in Scotland and has subsequently been critiqued as methodologically flawed, it was warmly embraced in England, especially by Rose who was an advocate of synthetic phonics.

The 2006 Rose Report was influential in shaping early reading pedagogy in England and from 2010 systematic synthetic phonics, not only became the exclusive method of teaching early reading in English schools, it was made statutory by the newly elected Conservative-Liberal Coalition under David Cameron. The then Education Secretary, Michael Gove, and his Schools’ Minister, Nick Gibb, announced a match funded scheme in which schools were required to purchase a synthetic phonics program. Included in the list of recommended programs was one owned by Gibb’s Literacy Advisor. This program is now used in 25% of English primary schools. In 2012, Gove introduced the phonics screening check for all Year One students (5-6 year olds) in England, and in 2017, Gibbs toured parts of Australia promoting the test here.

To what extent has the Phonics Screening Check been successful?

In its first year, only 58% of UK students passed the test, but in subsequent years’ results have improved. Students who fail the test must re-sit it at the end of year Two. By 2016, 81% of Year One students passed the test, but since then there has only been an increase of 1%.

Gibb cites this increase in scores, over a six-year period, as proof that the government has raised standards in reading and advocates of the test in Australia have seized upon the data as evidence in support of their case.

At face value, the figures look impressive. However, when we compare phonics screening check results with Standard Assessment Test (the UK equivalent to NAPLAN) scores in reading for these students a year later, the results lose their shine. In 2012, 76% of Year Two students achieved the expected Standard Assessment Test level in reading, but last year only 75% achieved the same level. Clearly then, the phonics screening check is not indicative of general reading ability and does not serve as a purposeful diagnostic measure of reading.

In a recent survey of the usefulness of the phonics screening check in England, 98% of teachers said it did not tell them anything they did not already know about their students’ reading abilities. Following the first year of the test in 2012, when only 58% of students achieved the pass mark, teachers explained that it was their better readers who were failing the test. Although these students were successfully making the letter-sound correspondences in nonsense words, in the blending phase, they were reading real words that were similar to the visual appearance of the pseudo words.

The conclusion is that authentic reading combines decoding with meaning.

Furthermore, as every teacher knows, high status tests dominate curriculum content, which in this case, means that by giving greater attention to synthetic phonics, in order to get students’ through the test, there is less time to give to other reading strategies.

Whilst the systematic teaching of phonics has an important place in a teacher’s repertoire of strategies, it does not appear to make any sense to make it the exclusive method of teaching reading, as is the case in England. To give it a privileged status as a test does exactly that.

Perhaps this is the key reason why, in England, phonics screening check scores have improved but students’ reading abilities have not.

I don’t think Australia should be heading down the same dead-end path.

Dr. Paul Gardner is Senior Lecturer in Primary English, in the School of Education at Curtin University. Until 2014, he taught at several universities in the UK.

This article was originally published on EduResearch Matters. Read the original article.

Stop worrying about screen 'time'. It's your child’s screen experience that matters!

10 min read

Brittany Huber, Swinburne University of Technology

Most (80%) Australian parents worry children spend too much time with screens.

But what children are doing on and off screen matters more than how much time they’re exposed to screen media.

Too much time?

There was a time when society was concerned about children reading. If kids are reading, how will they complete their chores or homework?

The fear that time spent with media replaces other “acceptable” activities of childhood is often referred to as the displacement hypothesis. One such concern is that screen time occupies time spent on physical activity.

Read more: What is physical activity in early childhood, and is it really that important?

Because screen time is often sedentary, researchers have investigated whether it displaces the time children spend being physically active. But the relationship between screen time and physical activity is not straightforward.

Low levels of screen time do not always equate to higher levels of physical activity. And when there is a relationship between more screen time and less physical activity, it’s often a result of excessive daily screen time.

The Australian guidelines on physical activity and sedentary behaviour advise children under two avoid screen time entirely. But a nationally representative poll conducted by the Royal Children’s Hospital found 63% of children aged two and under had screen exposure.

For children aged two to five, the Australian guidelines encourage parents to limit the time children spend with screens to no more than one hour a day. The child health poll found around 72% of children in this age group exceeded this recommendation.

Read more: Look up north. Here's how Aussie kids can move more at school, Nordic style

So, most Australian families are exceeding the guidelines, which are essentially built on a premise that isn’t clear-cut. Not all screen time is “bad”.

Is screen time bad?

A 2004 study from the United States explored the average time children spent watching television per day when they were aged one and three, and whether this affected their attention span in later years.

They found watching TV in the early years was associated with a higher risk of attention problems when these children were seven. But the research didn’t test the types of programs the children were watching.

In 2007, the same researchers looked at the effects of the content children watched. They found an association between watching violent or entertaining television such as Scooby Doo and Rugrats before the age of three and an increased risk of attention problems five years later.

But there was no such association when it came to educational content such as Sesame Street.

So, content plays a role, but the child’s age also matters. In this same study, the type of content viewed by four- and five-year-olds did not affect their attention five years later.

The above studies describe changes over time. But other studies looked at the immediate effects of different screen content on children’s executive functioning – the thinking required to problem solve and stay on task.

Read more: Two-hour screen limit for kids is virtually impossible to enforce

These studies found exposure to educational content didn’t hinder children’s subsequent executive functioning. But these abilities were depleted in four- and six-year-olds who had just watched fast and fantastical shows that played with the bounds of physics and reality.

What if you use screens with your children?

Decades of television research has shown children under three years old learn better from live interactions than from two-dimensional sources. So, these young children have little to gain from screens in the absence of a parent or peer.

Television meant for adult audiences, as well as television on in the background, disrupts the quality of children’s play and parent-child interactions that are critical for early language and social development.

The adverse effects of this type of screen exposure are due to limiting both the frequency and quality of interactions between child and caregiver. In the presence of background television, parents are less attentive and responsive to their child.

Read more: Let them play! Kids need freedom from play restrictions to develop

Parents’ own device use can be detrimental to the interactions they have with their children. Smartphone use can cause parents to be less attentive and responsive to their children.

All this is important to be mindful of, especially during the early years when these interactions directly contribute to language learning and social skills.

But what about if a parent uses a screen together with their child?

A 2014 study found preschoolers’ storybook comprehension and parent-child interactions did not significantly differ between a traditional book and an electronic book.

However, the quality of play and parent-child interactions are reduced with electronic toys as compared to traditional toys.

So, what screen time is OK?

To have healthy, positive, quality screen media experiences, parents could ask the following questions:

Is the screen content

-

optimally challenging (meaning not too difficult or too easy)?

-

engaging (does it have age-appropriate features that maintain attention and invite participation)?

-

meaningful (can children relate the content to their lives)?

-

interactive, in the physical or social sense. Young children can actually form relationships with screen characters, which improves their learning. Older children can engage virtually in worlds such as Minecraft, then talk about it in school.

Sharing the screen experience with an adult has benefits too. These include helping children understand the content and having an adult direct learning and ask questions.

The best way to engage in screen time with your children is to talk about it, ask questions and create opportunities to take the screen into the 3D world.

And, importantly, model the media use behaviour you want your children to adopt.

By occasionally employing the “digital babysitter”, you are not dooming your children’s success. What children are doing matters just as much, if not more, than how long they’re doing it for.

Brittany Huber, Postdoctoral researcher, Swinburne University of Technology

This article is republished from The Conversation under a Creative Commons license. Read the original article.

Kindy to Prep Transitions. A new mindset for all Catholic Schools. St Therese's School Bentley Park

Website: www.stthereses.qld.edu.au

A Transition Initiative that encounters the Reggio Emilia Philosophy of Early Childhood.

A position paper by Principal Colleague David Adams-Jones

Click the button to read.

Grateful Acknowledgements to the Authors:

Jacquie Jackson Assistant Principal St Therese's School Bentley Park

Christine Stratford Catholic Education Services Cairns

David Adams-Jones Principal St Therese's School Cairns Bentley Park.

Aleesha Exarhos

David Adams-Jones - St Therese's School

Phone: 07 4055 4514

Email: principal.bentleypk@cns.catholic.edu.au

What's the point of education? It's no longer just about getting a job

Long read

Luke Zaphir, The University of Queensland

This essay is part of a series of articles on the future of education.

For much of human history, education has served an important purpose, ensuring we have the tools to survive. People need jobs to eat and to have jobs, they need to learn how to work.

Education has been an essential part of every society. But our world is changing and we’re being forced to change with it. So what is the point of education today?

The ancient Greek model

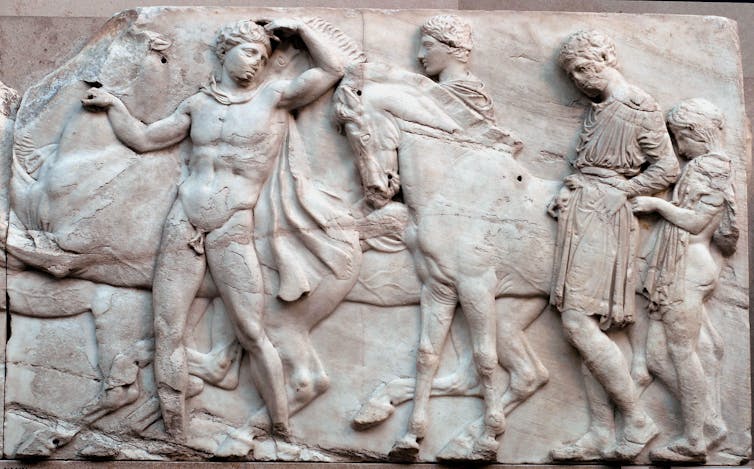

Some of our oldest accounts of education come from Ancient Greece. In many ways the Greeks modelled a form of education that would endure for thousands of years. It was an incredibly focused system designed for developing statesmen, soldiers and well-informed citizens.

Most boys would have gone to a learning environment similar to a school, although this would have been a place to learn basic literacy until adolescence. At this point, a child would embark on one of two career paths: apprentice or “citizen”.

On the apprentice path, the child would be put under the informal wing of an adult who would teach them a craft. This might be farming, potting or smithing – any career that required training or physical labour.

The path of the full citizen was one of intellectual development. Boys on the path to more academic careers would have private tutors who would foster their knowledge of arts and sciences, as well as develop their thinking skills.

The private tutor-student model of learning would endure for many hundreds of years after this. All male children were expected to go to state-sponsored places called gymnasiums (“school for naked exercise”) with those on a military-citizen career path training in martial arts.

Those on vocational pathways would be strongly encouraged to exercise too, but their training would be simply for good health.

Read more: Guide to the classics: Homer's Iliad

Until this point, there had been little in the way of education for women, the poor and slaves. Women made up half of the population, the poor made up 90% of citizens, and slaves outnumbered citizens 10 or 20 times over.

These marginalised groups would have undergone some education but likely only physical – strong bodies were important for childbearing and manual labour. So, we can safely say education in civilisations like Ancient Greece or Rome was only for rich men.

While we’ve taken a lot from this model, and evolved along the way, we live in a peaceful time compared to the Greeks. So what is it that we want from education today?

We learn to work – the ‘pragmatic purpose’

Today we largely view education as being there to give us knowledge of our place in the world, and the skills to work in it. This view is underpinned by a specific philosophical framework known as pragmatism. Philosopher Charles Peirce – sometimes known as the “father of pragmatism” – developed this theory in the late 1800s.

There has been a long history of philosophies of knowledge and understanding (also known as epistemology). Many early philosophies were based on the idea of an objective, universal truth. For example, the ancient Greeks believed the world was made of only five elements: earth, water, fire, air and aether.

Read more: Where to start reading philosophy?

Peirce, on the other hand, was concerned with understanding the world as a dynamic place. He viewed all knowledge as fallible. He argued we should reject any ideas about an inherent humanity or metaphysical reality.

Pragmatism sees any concept – belief, science, language, people – as mere components in a set of real-world problems.

In other words, we should believe only what helps us learn about the world and require reasonable justification for our actions. A person might think a ceremony is sacred or has spiritual significance, but the pragmatist would ask: “What effects does this have on the world?”

Education has always served a pragmatic purpose. It is a tool to be used to bring about a specific outcome (or set of outcomes). For the most part, this purpose is economic.

Why go to school? So you can get a job.

Education benefits you personally because you get to have a job, and it benefits society because you contribute to the overall productivity of the country, as well as paying taxes.

But for the economics-based pragmatist, not everyone needs to have the same access to educational opportunities. Societies generally need more farmers than lawyers, or more labourers than politicians, so it’s not important everyone goes to university.

You can, of course, have a pragmatic purpose in solving injustice or creating equality or protecting the environment – but most of these are of secondary importance to making sure we have a strong workforce.

Pragmatism, as a concept, isn’t too difficult to understand, but thinking pragmatically can be tricky. It’s challenging to imagine external perspectives, particularly on problems we deal with ourselves.

How to problem-solve (especially when we are part of the problem) is the purpose of a variant of pragmatism called instrumentalism.

Contemporary society and education

In the early part of the 20th century, John Dewey (a pragmatist philosopher) created a new educational framework. Dewey didn’t believe education was to serve an economic goal. Instead, Dewey argued education should serve an intrinsic purpose: education was a good in itself and children became fully developed as people because of it.

Much of the philosophy of the preceding century – as in the works of Kant, Hegel and Mill – was focused on the duties a person had to themselves and their society. The onus of learning, and fulfilling a citizen’s moral and legal obligations, was on the citizens themselves.

Read more: Explainer: what is inquiry-based learning and how does it help prepare children for the real world?

But in his most famous work, Democracy and Education, Dewey argued our development and citizenship depended on our social environment. This meant a society was responsible for fostering the mental attitudes it wished to see in its citizens.

Dewey’s view was that learning doesn’t just occur with textbooks and timetables. He believed learning happens through interactions with parents, teachers and peers. Learning happens when we talk about movies and discuss our ideas, or when we feel bad for succumbing to peer pressure and reflect on our moral failure.

Learning would still help people get jobs, but this was an incidental outcome in the development of a child’s personhood. So the pragmatic outcome of schools would be to fully develop citizens.

Today’s educational environment is somewhat mixed. One of the two goals of the 2008 Melbourne Declaration on Educational Goals for Young Australians is that:

All young Australians become successful learners, confident and creative individuals, and active and informed citizens.

But the Australian Department of Education believes:

By lifting outcomes, the government helps to secure Australia’s economic and social prosperity.

A charitable reading of this is that we still have the economic goal as the pragmatic outcome, but we also want our children to have engaging and meaningful careers. We don’t just want them to work for money but to enjoy what they do. We want them to be fulfilled.

And this means the educational philosophy of Dewey is becoming more important for contemporary society.

Part of being pragmatic is recognising facts and changes in circumstance. Generally, these facts indicate we should change the way we do things.

On a personal scale, that might be recognising we have poor nutrition and may have to change our diet. On a wider scale, it might require us to recognise our conception of the world is incorrect, that the Earth is round instead of flat.

When this change occurs on a huge scale, it’s called a paradigm shift.

The paradigm shift

Our world may not be as clean-cut as we previously thought. We may choose to be vegetarian to lessen our impact on the environment. But this means we buy quinoa sourced from countries where people can no longer afford to buy a staple, because it’s become a “superfood” in Western kitchens.

If you’re a fan of the show The Good Place, you may remember how this is the exact reason the points system in the afterlife is broken – because life is too complicated for any person to have the perfect score of being good.

All of this is not only confronting to us in a moral sense but also seems to demand we fundamentally alter the way we consume goods.

And climate change is forcing us to reassess how we have lived on this planet for the last hundred years, because it’s clear that way of life isn’t sustainable.

Contemporary ethicist Peter Singer has argued that, given the current political climate, we would only be capable of radically altering our collective behaviour when there has been a massive disruption to our way of life.

If a supply chain is broken by a climate-change-induced disaster, there is no choice but to deal with the new reality. But we shouldn’t be waiting for a disaster to kick us into gear.

Making changes includes seeing ourselves as citizens not only of a community or a country, but also of the world.

Read more: Students striking for climate action are showing the exact skills employers look for

As US philosopher Martha Nussbaum argues, many issues need international cooperation to address. Trade, environment, law and conflict require creative thinking and pragmatism, and we need a different focus in our education systems to bring these about.

Education needs to focus on developing the personhood of children, as well as their capability to engage as citizens (even if current political leaders disagree).

If you’re taking a certain subject at school or university, have you ever been asked: “But how will that get you a job?” If so, the questioner sees economic goals as the most important outcomes for education.

They’re not necessarily wrong, but it’s also clear that jobs are no longer the only (or most important) reason we learn.

Read the essay on what universities must do to survive disruption and remain relevant.![]()

Luke Zaphir, Researcher for the University of Queensland Critical Thinking Project; and Online Teacher at Education Queensland's IMPACT Centre, The University of Queensland

This article is republished from The Conversation under a Creative Commons license. Read the original article.

Would you like to get together for a drink or a meal when ACPPA meets in a capital city?

We have already received interest from past members…please email us now!

This photo below was taken at the 2005 Conference in Melbourne.

Great opportunties await for interested past ACPPA Executive to catch up occasionally!

Please contact Executive Officer – paul.colyer@acppa.catholic.edu.au

or Kevin Clancy kclancy@ozemail.com.au for more information.

SZapp...Have you downloaded yours yet?

Would you like ACPPA news and feeds straight to your phone… SZapp is here and can be downloaded on your device. Click the side bar to go to app store.

- Visit the app store for apple or playstore for android and type in SZapp in the search field

- Click icon that looks like this

- Click install

- Once installed Click open

- Click region Australia/Pacific

- Start typing Australian Catholic Primary Principals Assoc.

- Our logo and name should appear

- Registration required

- Register by Clicking and sign in with your email

- Create a password

REMEMBER...ACPPA 'Just the ESSENTIALS' is ONLY available through the APP

Download yours TODAY!