Work in schools long enough and we all get to know the bitter experience of a good idea poorly executed. We’ve all been there. The initial hope, and the eventual cynicism, as time/resources/training don’t quite live up to requirements and another good idea falls by wayside.

Thankfully the reverse is also true. We know that when good ideas are given a fighting chance they take root and become embedded in who we are and how we go about our work.

But what makes the difference between good implementation and another missed opportunity? What if we could bottle the habits of those teachers and leaders who are able to take a great idea and make it stick?

Implementation science – the study of the methods and strategies that lead to the adoption of proven approaches into routine practice (Global Alliance for Chronic Disease, 2019) – is beginning to help us understand and codify what it is that defines ‘good implementation’.

The Education Endowment Foundation has collaborated with the Centre for Evidence and Implementation to translate this emerging field into clear and actionable guidance for schools. Their work offers a framework for describing what it is that many schools do by instinct, but more often falls into what can best be described as uncommon common sense.

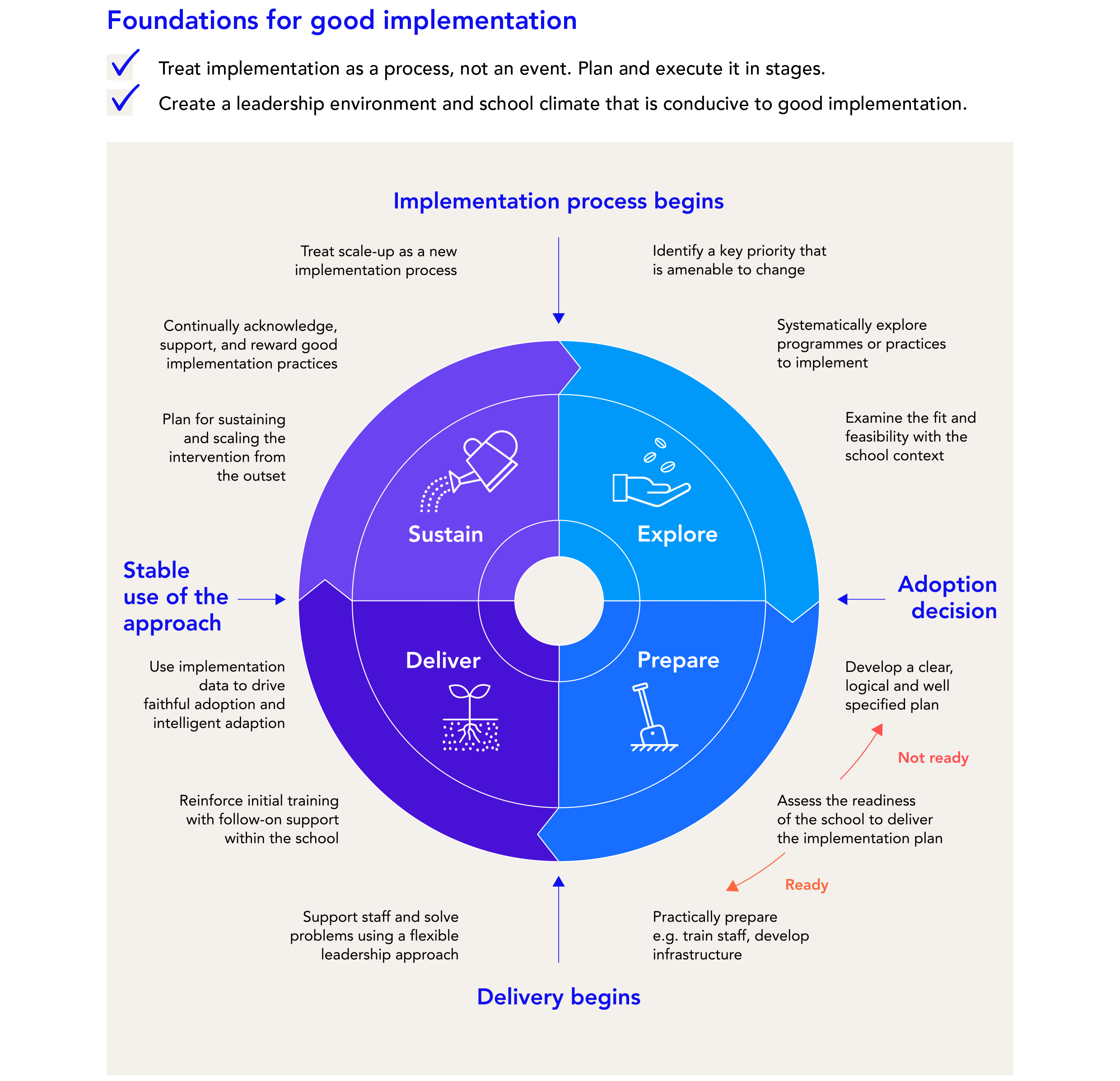

The framework starts with two recommendations to establish the critical foundations for success, without which it’s difficult for any school to move forward:

- Treat implementation as a process, not an event; plan and execute it in stages.

- Create a leadership environment and school climate that is conducive to good implementation.

With these foundations in place, the framework then defines four interconnected stages of implementation: Explore, Prepare, Deliver and Sustain.

Figure 1: The four stages of implementation (Sharples, Albers, Fraser, Deeble, & Vaughan, 2019).

This article follows one school’s implementation story, exploring how the framework describes the work of Canberra’s Richardson Primary School in implementing a culture of feedback and collaboration. The work continues today, and whilst it was led through the Explore, Prepare and Deliver stages by the then principal (our co-author Jason Borton), the ongoing work of the Sustain stage is now being led by his successors.

Taking a long-term approach

Treat implementation as a process, not an event; plan and execute it in stages.

In leading his team at Richardson, Borton knew that they needed to be in it for the long haul. If they were to succeed in embedding the mechanisms and structures that would support effective collaboration and feedback – such as instructional coaching and a peer-to-peer feedback model – then these needed to be given time to gain acceptance, and then be integrated within the day-to-day work of the school.

He spent a lot of time in the early stages setting the expectations and making it clear that this was a long-term change project. While some quick results might be seen for some students and staff, it would take time to see whole-school change. Communicating these expectations also helped create clear milestones for everyone involved: permission to pause and assess progress, and to change course if needed.

Giving it the best chance to succeed

Create a leadership environment and school climate that is conducive to good implementation.

Gardening offers some useful analogies for implementation science. Just as fertile ground can mean all the difference between oasis and barren wasteland, a school climate and culture that are conducive to learning and change gives implementation the best chance to succeed.

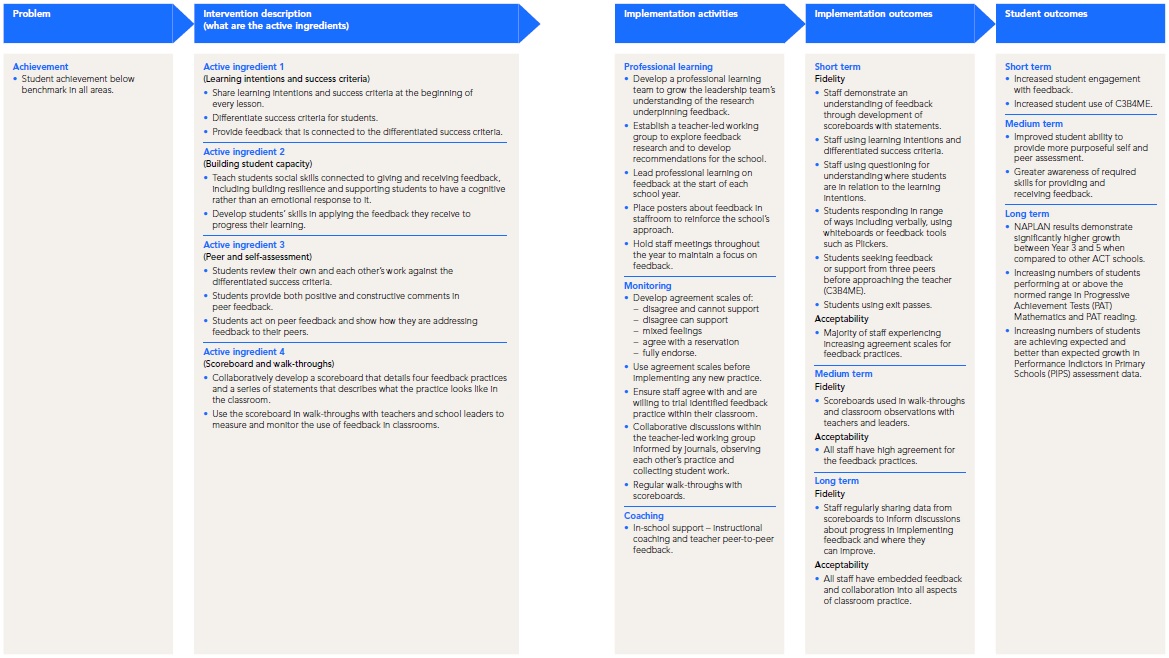

Borton knew from the outset that while his school had a trusting culture where teachers and support staff were generally receptive to taking risks, staff wouldn’t persevere with the change if they weren’t seeing direct benefits for students. He helped cultivate and support the school’s appetite to stay the course by creating agreement scales that enabled teachers to periodically rate and express their agreement to using a new practice (see Implementation Activities – Monitoring, in Figure 2 below).

Continually assessing how staff were experiencing the changes enabled reinforcement of an open and transparent leadership approach. This extended to school leaders maintaining a visible and active presence working alongside classroom teachers, to model a culture of support and development, rather than making judgements about performance.

Click here for a larger version of this image.

Figure 2: Implementation plan developed from a case study of Richardson Primary School (Sharples et al., 2019).

Starting with your own context

Define the problem you want to solve and identify appropriate programs or practices to implement.

In implementing change in a school, it’s imperative not to deliver a solution looking for a problem (Cain, 2019). Always start with your school, student and staff needs, and ask what evidence might offer to help you improve (Roberts-Hull & Vaughan, 2017).

At Richardson Primary School, Borton and his leadership team identified significantly low levels of achievement in both reading and writing. The leadership team were looking at an early intervention model, given that students were arriving in their first year of school already disadvantaged and many with significant developmental delays. The need for a whole school approach was clear, but it was the school’s teacher-led feedback group that reviewed the research on effective feedback and formative assessment and recommended the approaches they would use to get students back on track.

Ensuring a smooth implementation

Create a clear implementation plan, judge the readiness of the school to deliver that plan, then prepare staff and resources.

'Show don’t tell’ is probably the best approach here. Richardson’s implementation plan (Figure 2) exemplifies some of the key lessons from the implementation science. It clearly sets out:

- the approach to be implemented, including the active ingredients;

- the expected changes that will be seen;

- the implementation activities;

- the resources required; and,

- any external factors that could influence the results.

Jason created the plan to ensure that the implementation went as smoothly as possible. Further details of the work at Richardson Primary School can be read in this case study (AITSL and Evidence for Learning, 2017).

Two key highlights of the plan are: first, that it specifies the active ingredients of the change as those new ways of working that will be visible through either their presence in the school, or their absence – what will be different and how will we know it? The second key aspect is that the plan focuses on the implementation activities that will need to be in place for the new work to take root. These are generally tangible and practical steps that help the school become ready to implement the change. They are relatively simple to monitor, but if they’re not done successfully then it’s likely that the implementation won’t succeed. If students aren’t following ‘see three peers before me’ (C3B4ME), for instance, or teachers aren’t expecting them to, then peer-feedback won’t be given a fighting chance to work.

Once things are up and running

Support staff, monitor progress, solve problems, and adapt strategies as the approach is used for the first time.

Picking up the gardening analogy again, once the plants are in the ground they’ll need some love – weeding, mulching, pruning and watering – tending and shaping to keep things growing as intended. And of course, everything won’t go to plan. Some seedlings won’t survive, and some plants will need a bit more sun or a bit less water.

It’s the same with implementation in schools. Things won’t be perfect from day one, so we should put in place the monitoring systems to ensure the active ingredients are emerging in staff’s work, successes are being identified, problems are being dealt with, and that the school is generally changing in the right direction. Monitoring is key to ensuring that we learn about how the implementation process is going.

In Borton’s case, the instructional coaching and peer-to-peer feedback model were designed to explicitly nurture and support teachers to adopt agreed approaches and draw on the expertise of colleagues to problem-solve along the way.

Looking to the future

Plan for sustaining and scaling an intervention from the outset and continuously acknowledge and nurture its use.

Lasting change takes time to mature. But if it’s worth doing, then it’s worth doing well. At Richardson Primary School, Borton empowered a teacher-led working group to take carriage of the initial stages of the work. Staff in this group developed their collective expertise by observing each other’s practice and collecting student samples. If a practice was found to work well within their own classrooms, then it was shared with the wider staff to bring it to scale. This work was recorded using scoreboards that detailed four feedback practices and teamed those with walk-throughs to ensure that the changes in practice were sustained.

This process took three years to develop and has become an ongoing part of how the school grows, tracks and monitors the success it is helping to create for students.

Conclusion

Teaching students to learn is one of the most complex of all human endeavours. We should expect it to be difficult, and for change and improvement to be demanding. But get it right, and the rewards are well worth the effort for staff and students alike. By codifying and describing what effective schools do to succeed, implementation science offers the promise for schools to be more reliable in their introduction of new and promising ideas.

At Richardson Primary School, teachers have used the experience to develop a new set of skills that have enabled them to become good at getting better. The next frontier is to use that expertise to introduce a more systematic approach to instructional coaching – and they’re confident they’ll succeed.

References

AITSL and Evidence for Learning. (2017). Feedback Case Study: Engaging staff in Leading Change, Richardson Primary School, Canberra, ACT. Retrieved from https://www.aitsl.edu.au/teach/improve-practice/feedback

Cain, T. (2019, January 25). Don’t be a research fundamentalist. Retrieved from https://www.tes.com

Global Alliance for Chronic Disease. (2019). Implementation science. Retrieved from https://www.ucl.ac.uk/gacd/research/implementation-science

Roberts-Hull, K., & Vaughan, T. (2017, August 30). Four issues schools face when using evidence for improvement. Retrieved from https://evidenceforlearning.org.au

Sharples, J., Albers, B., Fraser, S., Deeble, M., & Vaughan, T. (2019). Putting Evidence to Work: A school's Guide to Implementation. Retrieved from https://evidenceforlearning.org.au

What is a tight area of focus for improvement at your school that is amenable to change?

What are some active ingredients related to the focus area for improvement?

As a school leader how do you structure professional learning at your school prior to and during implementation to ensure it has best chance of success?